"Sandy's Story" is an unprecedented look at the cruel journey of a vibrant, once healthy man as he gradually loses his memory. Sandy Halperin, a dentist and Harvard assistant professor, was diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer's disease at age 60. Instead of giving up in the face of his diagnosis, he's fighting back. This is the first chapter of his journey.

By Stephanie Smith, CNN. Photographs by John Nowak, CNN

Tallahassee, Florida

Sandy Halperin closes his eyes. His expression is placid, his mouth slightly upturned. Memories, like glints of light, dance inside his mind — a kind of neural film strip.

It is 1962. He is in a small neighborhood pharmacy in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father, the pharmacist, hands a customer a wooden nickel, good for a free cup of coffee while she waits.

He sees his 12-year-old self standing over a towering hot fudge sundae at the soda counter. The smell of warming cashews and peanuts curls out of a corner machine.

Then, as the mind is wont to do, Halperin's memory leaps to a different time. He is 8 years old, standing next to his father behind the counter.

His fingertips are flecked with white as he fills empty capsules with medication, clasping them together before handing them off to his father.

Halperin slowly sighs. His eyes flutter open as the reverie ends. Whatever soundtrack his mind generated to accompany memories of his father's pharmacy dies out, replaced by the din of cicadas.

"Those days with my father influenced my life forever," he says, before his voice trails off. "I remember it. I can shut my eyes and see it, yet I won't remember the movie I saw last night."

Alexander "Sandy" Halperin sits on a bench, surrounded by gnarled oak trees, at the retirement village in Tallahassee where he lives with his wife. His face is framed by a thick, graying beard; the rest of it is smooth — almost too smooth for a 64-year-old.

He has an engaging manner of speaking. He looks you in the eye intently, at times waving his hands to make a point, or lightly touching your arm.

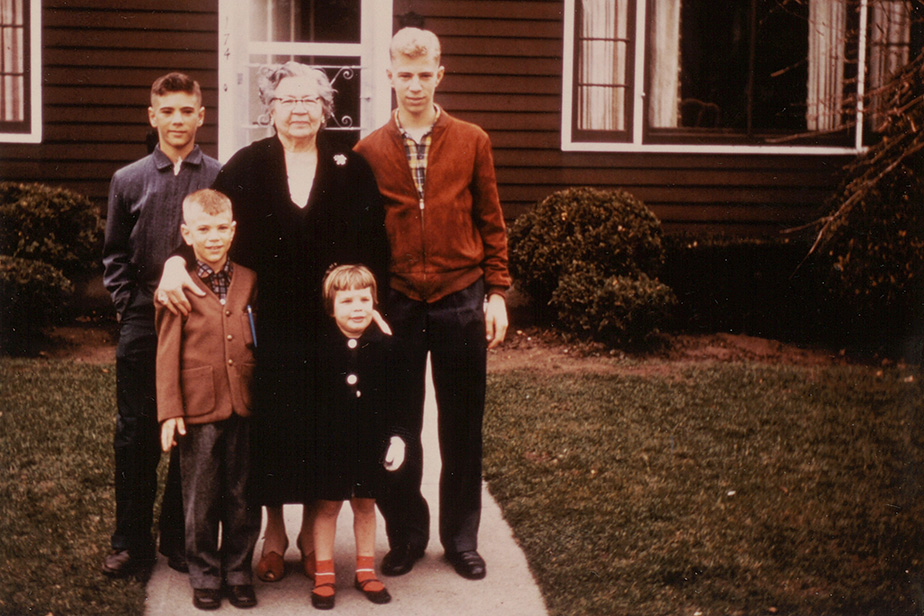

Sandy Halperin's paternal grandmother Bessie also had Alzheimer's disease. She poses here in 1957 with (from left) Halperin's brother Mark, Halperin at age 7, his cousin Anita and his brother Joe.

Courtesy Halperin Family

If you were not paying close attention, you might never know Halperin has dementia. Doctors diagnosed him with early stage Alzheimer's in 2010.

For years, the former dentist and assistant professor at Harvard has relied on what you might call considerable "cognitive reserve" — his ailing mind seeming to carve novel cognitive pathways, even as his disease course worsens.

"He is a very inventive and creative person; he always has a lot going on, always able to juggle a million things," says Lauren Halperin, 32, his younger daughter.

But lately, that inventiveness is withering. He punctuates most thoughts with an apologetic "I forgot what I was saying," or a more frank, "I lost it..."

When he tries to follow a conversation's twists and turns — or recall the minutiae that form a productive day — the "I forgots..." and "Where did I leaves...?" and "Have you seens...?" can seem relentless.

Call them conversational hiccups. Except these hiccups aren't abating — they will only get worse.

"I see a lot more frenzy and desperation in his communications with people now," says Karen Halperin Cyphers, 34, Sandy's older daughter.

She compares it to what her 3-year-old does when she is asked to take something to the trash.

"The whole way to the trash she says 'Bring this to the trash, bring this to the trash, bring this to the trash,'" Cyphers says. "I see that happening (with my father).

Sandy Halperin says that, at times, his memory loss causes emotional pain. “All we really are is our thoughts," he says.

"I see him thinking, 'I know what I need to say; I know what I need to say; I'm gonna say it ... right now!"

At times, the memory loss is painful, Halperin says.

"All we really are is our thoughts," he says. "So this is a different kind of pain. The pain is emotional."

According to research published in March by the Alzheimer's Association, among people 60 and older, an Alzheimer's diagnosis stirs more fear than any other disease — even cancer or stroke.

Worldwide, there are around 44 million people living with Alzheimer's and other dementias, according to the Alzheimer's Association. In the United States, more than 5 million people have Alzheimer's disease, but only half are formally diagnosed.

Losing the ability to think and recall — what could be defined as the very essence of being human — is almost universally terrifying. So terrifying that many people dwell for years in a state of denial.

Denial, it would seem, shrouds the mind from dementia's more appalling images: Patients shuffling aimlessly around a nursing home in wheelchairs, despondent. Or the converse image of the agitated patient thrashing wildly with no concept of where –- or even who — they are.

Sandy Halperin was a teacher and practicing prosthodontist at Harvard University in 1979. In this photo he is working on his own father's teeth.

Courtesy Halperin Family

Halperin bristles at those images of the Alzheimer's patient. While they may capture what the disease looks like during later stages, he says, they ignore what could be many productive years leading up to them.

In those years, he says, it is possible to live vitally, despite deficits. It is precisely the stage he is in.

As best as he can, Halperin has remained active and social — dining with other residents at his retirement village and taking walks or twilight swims to try and delay, at least for a while, the symptoms of his disease.

He also has become a fervent activist — giving talks about stigma, lobbying Congress — and has an online network of Alzheimer's patients, advocates and physicians numbering in the thousands.

"My focus right now is to help break the thinking that the patient that has Alzheimer's is sitting in a nursing home," he says, the passion building in his voice.

"I'm alive. I can still be proactive."

Snowballs

In Halperin's mind, it is 1956. He is 6 years old.

Snow blankets the ground outside. He is curled up on the couch, hugging his legs as his infected lungs spasm.

He can hear the faint sound of his brothers gleefully screaming during a spirited snow fight with other neighborhood children.

The door flings open. His two older brothers drop a bin filled with snow on the kitchen table.

Sandy's wife Gail Halperin, 72, says that while Alzheimer's is a devastating disease, her husband's proactive response to his diagnosis has helped her to cope.

Halperin can almost feel the cold grip his fingers now as he relates how — unable to withstand the weather outside — he often made snowballs from inside the house.

"I was coughing away and sick, so to make me feel good my brothers would bring in the snow," he says. "I would make the snowballs and put them in the freezer so that they'd be ready for their war, their snowball fight with their friends."

Memories, mostly from long ago, have become a type of cognitive balm, thoughts to which he clings, tightly, since his diagnosis. He finds comfort in old memories because they are still available to him.

"My biggest problem is my short-term memory," he says. "It's my ability to recall what I said, what I did, what I need to do, and that's steady through a day."

More elusive the past few years: The movie he watched last night; the product he drove to get at the grocery store; or worse, where he put the car he needs to get to the store in the first place.

Halperin realized he had progressed from garden-variety memory loss — losing keys, forgetting a name — to something far worse six years ago, when he worked for the Florida Department of Health.

His job involved reviewing dental cases for attorneys considering the merits of patient complaints before the department. He would be handed case files, sometimes hundreds of pages long, and issue a written or verbal report.

His recollection of even the tiniest detail contained in a case he was reviewing had been impeccable. It seemed to sneak up on him one day: His memory of a case vanished.

"I am looking at (the case file) for an hour and a half," he recalls. "I'm reading it, it's in my brain. Then I would close the file and not remember literally anything about the case."

Sandy and Gail Halperin, early in their marriage, in 1975.

Courtesy Halperin Family

It started to happen more and more frequently.

When an attorney would come to his office to discuss a case, Halperin would make an excuse to meet a few minutes later. Almost as soon as the attorney left his office, he would desperately try to cram the details into his brain.

He would then run to his colleague's office to try and relate the information before it escaped him again. That desperate scramble worked — for a little while — until it became exhausting.

"I would be dizzy and could hardly sit there and concentrate," he says of those meetings. "But I was able to get through the conversation, trying to get out of there as soon as I could."

It is the only time he says he hid his symptoms.

When it became too much to bear, Halperin sought help. After a series of misdiagnoses, he was finally told he had early stage Alzheimer's disease.

"It is a horrifying, gripping, devastating disease that plays havoc on the family and on the patient," says Gail Halperin, Sandy's wife.

But, she says, what has softened the blow of Halperin's diagnosis is the way he responded to it — at least after the initial stunned feeling subsided.

"He immediately came out and said, 'I don't want to cover this up. I want to share it with people and be proactive,'" his wife says.

Recent data suggest that such a response is rare: Nearly 13% of Americans reported experiencing worsening confusion or memory loss after age 60, but most — 81% — had not consulted with a health care provider about their cognitive issues, according to the March Alzheimer's Association report.

"For some reason, it's embarrassing to people that they have this (disease), and it doesn't make sense," says Lauren Halperin, adding that some ignore their symptoms, waiting until the last possible moment to seek medical help.

Sandy Halperin tickles his granddaughter Madeline, 3, while his other granddaughter Rebecca, 4, looks on.

There is no cure for Alzheimer's disease, but certain medication combinations — and lifestyle interventions — may help with symptoms associated with dementia.

"By the time they go on medication, not to say it's too late, but they've lost some potentially valuable time," she says. "And I think (my dad) feels like, 'enough of that.'

"If this is something you have, don't be ashamed of it. Go do something so that you can have more time.'"

Living in the 'precious' present

Four years after being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, Halperin says the flickering lights of times past still cast a glow in his mind.

Some days, the glow is barely perceptible. Other days, it burns bright. What he is learning, he says, is to let whatever state his memory is in during a particular day — be.

He often quotes a book, "The Precious Present," by Dr. Spencer Johnson, a contemplation of what it might mean to live in the moment.

Sandy Halperin poses with his daughters Karen, left, age 4, and Lauren, age 2, at their home in Needham, Massachusetts, in 1984.

Courtesy Halperin Family

One of the book's more poignant passages describes how Halperin is attempting to live with Alzheimer's: "It is wise for me to think about the past and to learn from it, but it is not wise for me to be in the past, for that is how I lose myself."

It is a towering sentiment — one that he tries in earnest to embody. It's made even more meaningful now that Halperin is noticing not just his short-term memory flagging, but also his long-term.

The gravity of that loss breeds wonder. Will his granddaughters remember him when they get older? Has he taught them enough about what it means to be a Halperin? Will they absorb enough of the spirit of giving and joy he got from his family while growing up?

"I want them to feel what it's like to have a grandpa," he says wistfully.

Almost as soon as he says it, Halperin engages in the sort of mental tug-of-war he will likely play for the rest of his life: He stops himself from thinking about what might be, and thinks about now.

"The other day I had a joyful moment with my granddaughter Rebecca," he said. "I was tickling her and she said something to the effect of 'Grandpa, that was a great tickle.'

"That was like, 'Melt my heart, let me do it again.'"

This moment.

Right now.

Soon, it may be all Halperin has.

And that is OK.

CNN HEALTH

Overwhelming burden, cost of Alzheimer's to triple

By 2050, the number of people worldwide who live with dementia is expected to more than triple to 115 million. The majority require constant care; they're dependent — and that dependence can impact their loved ones in unmeasurable ways.

The 10 warning signs of Alzheimer's

Ask any expert, and he or she will tell you that early diagnosis is key to helping Alzheimer's patients live better day to day, so even though the disease is still progressing, the symptoms are less harsh.

CNN 10: Healing the Future

These 10 ideas are revolutionizing health care — from the operating table to the kitchen table. Even those that don't come to fruition as imagined will have forged a path for another that will one day save a life.

Sweet comparisons: How much sugar is in that drink?

Sugar has become public enemy No. 1 in the nutrition field — doctors and public health advocates alike are "Fed Up" with the amount Americans are consuming.