-

Introduction

-

Bolivia

-

Malawi

-

Mongolia

-

Idaho

-

Romania

-

Cape Breton

-

Arctic Circle

-

Bhutan

-

Northland

-

Space

Up for a challenge?

You don't have to be an adrenaline junkie to take a dare.

Maybe a subtle shift in direction is enough to feel the excitement. Or is it the thrill you'll get from telling family and friends about your slightly unconventional travel plans?

We've picked 10 places we think are well worth a stop on your global adventure.

Choose a bold, unspoiled escape: a high mountain haven in Asia, or a pristine lake in a sliver of Africa. Follow in the footsteps of nomads and warriors. Meet people carrying on ancient traditions.

We won't send you into war zones or jumping out of airplanes. But we haven't ignored thrill-seeking altogether (blasting off to space is still on the table).

Mostly, though, we invite you to venture to overlooked, lesser-known or emerging spots.

We’ll give you a bird’s-eye view of countries often overshadowed by their flashier neighbors. And we'll take a deeper dive into less-familiar regions of places that see their fair share of tourists.

From the planet’s northernmost pinnacle to a South American salt desert, we dare you to go somewhere different.

May we present the CNN 10: Dare to Go.

Sucre, Bolivia, is known for its lovely colonial architecture. (Michael S. Lewis/National Geographic)

A land of contrasts

First, some things you won’t readily find in Bolivia: resorts, destination restaurants, stretches of paved highway or reliable public transportation.

That friend who craves “authentic” travel experiences will be well-served in Bolivia.

What this South American country lacks in first-world comforts it makes up for in unvarnished experiences in a diverse territory stretching from the peaks of the Andes to the Amazon basin.

One day, you could be snapping goofy perspective shots in the world’s largest continuous salt desert, the Salar de Uyuni; or hiking Isla de Sol in the middle of Lake Titicaca, the world’s highest navigable lake.

The next day, you could be eating grilled cow hearts from a street cart in La Paz.

“You’ll almost always have the impression of discovering something real and have the chance to share the realities of Bolivians,” said Alexandra Hitter, who lived in Bolivia for two years while working for an international aid group.

“Wherever you go in Bolivia, you’ll have plenty of stories to tell when you get back home, no doubt. Especially if you travel by bus, during social protests.”

Anyone spending a few days in Bolivia is likely to encounter a protest or roadblock in ongoing disputes between the government and Bolivia’s indigenous people, who make up more than half of the population. It’s why air is the preferred method of travel for visitors short on time, patience and anti-nausea medication.

The cultural traditions of the Quechua and Aymara permeate daily life, from the pottery and textiles sold in the markets to the hearty cuisine sold from street carts.

Some of Bolivia’s most popular destinations are tried and tested by decades of visitors, even the so-called Death Road outside La Paz that draws cyclists and drivers from around the world.

In La Paz, the world’s highest administrative capital at about 12,000 feet above sea level, most tourists peruse Sagarnaga Street for cheap goods, but the Sopocachi zone is also worth visiting for a modern Bolivian meal or to catch a movie at the Cinemateca Boliviana.

Backpackers and families are known to spend weeks in picturesque Sucre, the country’s constitutional capital, studying Spanish and taking in the city’s colonial past through its museums and tranquil central plaza.

Fewer visitors travel from Sucre to Tarabuca for the Pujllay Festival in March to celebrate harvest toward the end of the rainy season, but it’s worth the two-hour journey.

In the dry season, consider venturing outside Sucre on horseback with a cowboy to discover its hills and cuisine.

Salar de Uyuni is the world’s largest continuous salt flat. (Michael Kittell/Rex Features/AP)

Crystal-clear Lake Malawi occupies one-fifth of the country. (Bill Curtsinger/National Geographic/Getty Images)

An unspoiled retreat

Overlooked for more popular destinations such as Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa, Malawi has its share of pristine scenery, wildlife reserves and natural landscapes -- and you’ll have more of it to yourself.

Serene and friendly, it’s an easy place to visit. The trend here, say tour companies, is to rent a car and drive yourself through the southeastern African nation’s forests, rolling plains, mountains and wetlands. The slim landlocked country stretches about 520 miles from north to south.

Its crowning jewel is Lake Malawi, a giant freshwater lake that lies on a stretch of the northeastern border. The lake, also called Lake Nyasa, occupies one-fifth of the country’s total area and is its lifeblood.

Its beaches are golden and the waters are usually nearly empty. Remember your sun protection -- the sun shines powerfully in Malawi, especially during the dry season from May to November.

For science lovers, the lake boasts up to 1,000 fish species, more than any other lake in the world. Nearly all of the fish species are endemic. Declared a UNESCO heritage site, the water is remarkably clear and perfect for freshwater snorkeling and diving.

If fish aren’t your thing, the lake also draws a variety of bird species, as well as hippos, warthogs, baboons and occasional elephants.

Another appeal of Malawi is the friendliness exuded here. Locals wave at you readily, and many will strike up conversations. For a well-worn traveler, this may at first arouse suspicion, but the people are genuinely warm and curious about foreigners.

It’s called the “Warm Heart of Africa” for a reason.

People want to chat. Where are you from? Is this your first time in Malawi? Enjoy the opportunity to engage, as English is one of the major languages.

Since the country’s founding in 1964, there has never been a civil war in Malawi. It’s considered a safe and very welcoming place to visit.

Consider combining two of Malawi’s best assets – the people and the lake – at one of Africa’s most respected festivals.

The tourism minister once skydived into the Lake of Stars festival, where Malawian music fuses with styles including Swedish electronic dance music. The 2014 festival is scheduled for September 26-28.

If it’s wildlife you’re after, there are safaris. Wildlife reserves are stepping up conservation, restocking animals and getting into the Big Five game (elephant, rhino, lion, leopard, buffalo).

Elephants gather at Liwonde National Park. (Ian Cumming/National Geographic)

Horses are central to Mongolia’s nomadic culture. (Ben Horton/National Geographic)

The great wide open

Mongolia is often stereotyped as a large, empty country filled with nomadic herders and Buddhist temples.

The image isn’t wrong.

Mongolia is more than twice as large as Texas but contains just 3 million people, the lowest population density of any independent country. And yes, there are many Buddhist monasteries spread throughout the land.

But that image conceals a curious history. Some monasteries were destroyed in the 1930s during an era of Stalinist repression. Development in Ulaanbaatar, the capital, has really taken off only in the last few years, though the city dates back to the 1700s.

Still, Mongolia’s wide-open spaces and spiritual quietude are the main attraction, says Jonathan Khoury, vice-president of Blue Silk Travel, a Wisconsin-based agency that specializes in Mongolian tourism.

“As soon as the city ends, you’re going to see someone on horseback riding and living in a ger (yurt, the distinctive homes of Central Asia), moving with the seasons and raising animals,” he says.

Mongolia is the ancient land of Genghis Khan, who founded the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. At its peak in the late 1200s, the empire stretched thousands of miles from present-day China to Eastern Europe.

Eight centuries later, the country is still best appreciated amidst its nomadic culture, taking time to ride on horseback (or on camels, if you’re so inclined).

If you arrive during Naadam – the national festival usually held in mid-July – you can see the “three games of men”: horse racing, wrestling and archery, the main competitions for ancient soldiers, says Gan-Ochir Zunduisuren of VisitMongolia.com.

Don’t be afraid to mix with the locals. Even in the most remote areas, says Khoury, people are eager to meet foreigners, and they will open their homes to strangers.

Mongolia’s landscapes are spectacular. Visit the Gobi Desert, one of the most remote places on the planet, where you may see wild camels, the Singing Dunes or Gobi bears. Central Mongolia features the greenery of Orkhon Valley, seat of ancient empires – including the ruins of Genghis Khan’s capital, Karakorum.

Mongolia isn’t for everybody. Winters are brutal: Ulaanbaatar, which contains half Mongolia’s population, is the coldest capital in the world. And though the city has modernized rapidly, it’s still playing catch-up from the years when it was full of bleak, Soviet-style apartment blocks.

Roads outside the capital are often no more than dirt paths; you’ll want a guide to help you get around and translate the language. Travel per person can run from $60 up to a few hundred dollars per day.

So, large and empty? Sure. But full of wonder.

The two-humped Bactrian camel is a native of the Gobi Desert. (Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Hundreds of alpine lakes dot central Idaho’s Sawtooth Range. (Michael Melford/National Geographic/Getty Images)

Beyond the potato

Ask someone from another part of the country what pops into their mind when they think of Idaho, and you might get a blank stare or a one-word answer: potatoes.

Which may explain why Idaho is not on many travel bucket lists. Honey, forget Bora Bora; let’s go to a potato farm!

It doesn’t help that unlike most of its neighbors in the American West, Idaho lacks a defining feature. Idaho is the only Western state without a major national park. It can lay claim to a sliver of Yellowstone, but 96% of that park is in neighboring Wyoming.

Thanks to many Americans’ tenuous grasp of geography, Idaho also often gets confused with Iowa, 1,300 miles away in the Midwest.

But don’t let Idaho’s image problem discourage you from planning a visit. The spectacular scenery of this overlooked state can hold its own with anybody’s, and -- unlike in Yosemite or Zion -- you won’t have to elbow your way through crowds to see it.

For starters, Idaho contains the deepest river gorge in North America, the second-largest wilderness area in the Lower 48, more miles of rivers than any other state and a waterfall that’s 52 feet higher than Niagara. That would be Shoshone Falls east of the city of Twin Falls on the Snake River, which carves a smile across the arid southern third of the state.

Idaho also has a colorful history of stubborn individualism, from Ernest Hemingway to “Napoleon Dynamite.”

Hemingway, the state’s most celebrated resident, wrote part of “For Whom the Bell Tolls” in Sun Valley. Daredevil Evel Knievel tried, and failed, in 1974 to leap across Snake River Canyon in a steam-powered rocket. And Napoleon rocked his geeky dance moves in the Mormon farming towns of the state’s southeast corner.

But the best reason to visit Idaho is the pristine beauty of its mountainous midsection and forested panhandle.

Start in the summertime in Boise – a handsome city with a compact, lively downtown – and drive northeast to Stanley, a frontier outpost in a gorgeous mountain valley flanked by the jagged Sawtooth Range and the middle fork of the Salmon River.

From there, you can hike to alpine lakes, cast for trout in meadow streams, raft down the Salmon or drive an hour south to the more refined resort-town charms of Ketchum and Sun Valley.

Or for a real adventure, pack a tent and head deeper into the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness Area, a vast swath of rugged forest that’s home to bears, moose, mountain lions and wolverines.

This, the heart of Idaho, is not for everyone. But if you want to lose yourself – find yourself? – in a rare expanse of unspoiled wilderness, it’s just the right place.

Shoshone Falls is often referred to as the Niagara of the West. (Jordan McAlister/Getty Images)

A shepherd tends his flock in Romania’s Carpathian Mountains. (Catherine Karnow/National Geographic)

Where history lives on

An inspiration for Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” Romania is a glorious and struggling country of contradictions.

Within its borders, hulking Stalinist architecture contrasts with spectacular medieval art and architecture.

These buildings bear witness to centuries of conflict. For hundreds of years, walled citadels and imposing castles were built to hold back the encroaching Ottoman Empire, sometimes without success. More recently, a modern era of brutality ended in 1989 with the execution of Communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu.

Today, Romania is moving unevenly toward modernization, yet much of the country’s allure comes from what hasn’t changed for centuries.

The country’s seven walled citadels and hundreds of medieval villages – some of which date back to the 13th century and are still used by farmers and townspeople -- are among the best examples of medieval Saxon architecture anywhere in Europe. (To learn more about rural life, visit the Romanian Peasant Museum in Bucharest).

You may even want to check into a medieval building-turned-guesthouse as a base for exploring Romania’s magnificent unspoiled nature.

The Carpathian Mountains of Southern Transylvania offer hiking and wolf- and bear-spotting. Also known as the Transylvanian Alps, the Southern Carpathians are lesser known than their Swiss cousins with more affordable winter skiing and summer exploration.

And don’t miss the inspiration for Dracula. The character was partly based on a brutal real-life 15th-century prince, Vlad Dracula, also called Vlad Tepes (the Impaler). Tourists flock to Bran Castle in Transylvania, a drawing of which is believed to have inspired Stoker.

Bran Castle was constructed in the late 1300s as a customs house and fortress. No matter that the real Vlad may not have spent more than a few nights at the real Bran Castle. (Vlad spent more time at Poienari Castle, which is in ruins.)

Head north about two hours to the 16th-century town of Sighisoara, the most famous of the country’s seven citadel towns.

This UNESCO World Heritage Site is a spectacular example of an almost perfectly preserved medieval fortified town, which in its heyday sat on the border between central Europe’s Latin culture and the Byzantine/Orthodox culture of Eastern Europe.

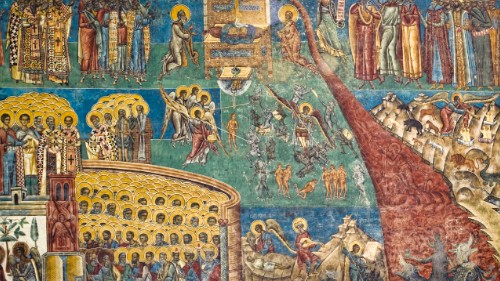

Head farther north to Voronet Monastery, one of the famed Painted Monasteries of Southern Bukovina, to see stunning 15th- and 16th-century Byzantine frescoes.

The Voronet Monastery was built by Stephen the Great in 1488. (Getty Images)

The Cabot Trail makes a loop around Cape Breton Island. (Raymond Gehman/National Geographic/Getty Images)

Real and rugged

Raw, rustic charm runs all the way through Canada’s Cape Breton Island. You’ll find it in the locals and the land and the toe-tapping music.

A rugged 110-mile-long island in northeastern Nova Scotia, Cape Breton sits between the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Atlantic Ocean, rising to the province’s highest point at nearly 1,750 feet above sea level.

Though not uncharted by scenery seekers, only one in five -- mostly Canadian -- visitors to Nova Scotia make it to Cape Breton, according to tourism figures. And less than 10% of international visits to Canada include Atlantic Canada at all.

To see what you’ve been missing, drive the Cabot Trail.

Cutting curly ribbons through the wilderness, the roadway loops around the northern part of Cape Breton, hugging the coasts for views that beg for a stop. You can finish the loop in a day, but to really explore, you’ll need longer.

Along the way, near-vertical rock faces plunge to the water below, while the textured terrain seems to mirror a hearty local blend of Scottish, Acadian, Mi’kmaq and Irish traditions.

John Cabot visited the island at the end of the 15th century, and it had stints as a colony of France and Britain before rejoining Nova Scotia in 1820.

Gaelic culture is thick here, with fiddle music at its core. Cape Breton native and award-winning fiddler Natalie MacMaster describes the sound as “a hand-me-down tradition.”

“The people and the lifestyle, it all goes, it all matches. Even the land, if you look at Cape Breton Island, it’s similar to the music in that it’s a rugged land, it’s beautiful, it’s strong, it’s not refined. It’s very, very natural.”

For pure nature, stop along the top of the Cabot Trail in Cape Breton Highlands National Park, where 26 hiking trails invite you to explore the wilderness on foot.

There’s rich history, too.

The impressive Fortress of Louisbourg recreates part of a key French trading harbor and fortified capital as it was during the 1740s when the island was known as Ile Royale. The site is on the eastern coast less than an hour from Sydney, the island’s urban center.

Just don’t lose yourself in sightseeing so much that you miss out on experiencing the traditional music at a ceilidh (pronounced kaylee), Gaelic for a party or gathering.

Check local listings, visit pubs such as the famous Red Shoe in Mabou, or attend a square dance at the West Mabou Hall, MacMaster suggests.

“What you see is what you get” in Cape Breton, she says. “It’s just an honest place in this world that really doesn’t change too too much.”

Fiddle music is a rich Cape Breton tradition. (Pete Ryan/National Geographic/Getty Images)

The North Pole is covered with large packs of floating ice. (Borge Ousland/National Geographic)

A frozen playground

Standing at the top of the world, skis sliding on the shifting ice: Reaching the North Pole is the trip of a lifetime for some daring adventurers.

Does it sound too cold and scary to you, or maybe like too much work?

Don’t give up on the Arctic Circle. The northern pinnacle is just one spot to explore in the Land of the Midnight Sun.

The Arctic Circle is made up of the area above the circle of latitude of 66°33′ N, encompassing parts of eight countries. The sun doesn’t set here for at least one day in the summer, with many more days of midnight sun the closer you get to the North Pole.

Across the region, you can search for the aurora borealis, see polar bears hunting their prey, or dogsled and ski along remote, frozen expanses before soaking your weary bones in natural hot springs.

For an extraordinary experience, veteran Arctic explorers recommend Norway’s Svalbard Islands, located in the Arctic Ocean about halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole.

Polar Explorers guide Annie Aggens and National Geographic photographers Sisse Brimberg and Cotton Coulson say that’s where you’ll find the best polar bear sightings in the world -- and plenty of other Arctic animals.

It’s also where you’ll stop on a summer National Geographic/Lindblad Expeditions cruise, where Brimberg and Coulson and other experts will explain the science behind the majesty of what you’re seeing and you’ll spot glaciers that have been receding since they’ve been visiting the Arctic. (Bundling up is still required.)

If you have more time, the islands have nature reserves, national parks, hot springs and Huset, a gourmet restaurant in Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town.

Looking to explore Inuit life in the Arctic? Although most of Greenland is still covered in ice (for the moment), about 57,000 people live in this self-governing territory of Denmark where Inuit culture is very much alive.

Hoping to entertain the little ones? Santa Claus is nearly always in residence at his home in Finnish Lapland (except on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and other public holidays).

If you’re set on planting yourself on the North Pole, you’ve got options. Polar Explorers offers chartered helicopter rides (no skiing required) to the Pole in April, when a Russian base camp is open. Starting at more than $21,000, this is definitely not your typical getaway.

For a heftier investment – both physically and financially – try a 10k ski trip with one night of camping at the North Pole, or ski the last half-degree (a week’s trip) or full degree (two weeks) to the Pole.

A polar bear peeks into a cabin in the Svalbard Islands. (Paul Nicklen/National Geographic)

Buddhist prayer flags hang near the clifftop Taktsang Monastery, or Tiger’s Nest. (Adrees Latif/Reuters/Landov)

A real-life Shangri-La

It’s not easy or convenient to travel to Bhutan, but that’s exactly why you should. You’ll be able to sense that the country was a hermit until recent years.

Actress Shirley MacLaine exposed Bhutan to Westerners in her 1970 memoir, “Don’t Fall Off the Mountain.” The kingdom was largely hidden from the world then and only began opening up in the decades since.

These days, Bhutan is the only remaining Buddhist state in that part of the world after the Chinese took over Tibet and Sikkim became a part of India.

It’s the only country in the world that measures prosperity not with GDP but GNH: Gross National Happiness. Bhutan is a real-life Shangri-La with near-mythical status. It presents challenges to thrill-seekers and has been described as catnip for spiritual wanderers.

It’s one of those few remaining places still untouched by the onslaught of modern connectivity and a Starbucks on every corner.

“In Bhutan, we are developing but we are very respectful of culture, our environment,” says Yeshey Wangchuk, 28, who has worked for seven years as a guide for visitors in his homeland.

Go before Bhutan becomes a destination in Asia.

And that might be soon. Tourism is fast growing, second only to hydroelectric power as a driver of the economy. Last year, Wangchuk says, 66,000 foreigners traveled to Bhutan.

Go to clear your head high in the clouds, to be touched by the sacred.

Bhutan is a land of magic in the mountains. The Snowman Trek along the spine of peaks that separate Bhutan from Tibet is one of the most difficult walking expeditions in the world. It takes 24 days and only a few hundred foreign visitors have completed the arduous journey.

You have to get over 11 high passes in the Himalayas, the world’s tallest mountains. That means you climb several thousand feet, then descend, then ascend again. Yes, 11 times. Whew.

Let’s just say more people have conquered Everest than succeeded at Snowman Trek.

If you are not in shape for that kind of intensity, there are plenty of other options.

Number one on Wangchuk’s list is Taktsang Monastery, more commonly known as Tiger’s Nest. It’s perched on a cliff 914 meters above the countryside. There are no good roads, no easy ways to get there. But the hiker’s reward is to experience one of the most important religious sites in Bhutan.

If nothing else, go to Bhutan to experience a place that measures prosperity not through growth and money but through the happiness quotient. Wangchuk insists his fellow citizens are content. So is he. And you can be too, in Bhutan.

Pack horses descend the 16,000-foot Nyile La pass in the Himalayas. (Alex Treadway/National Geographic)

Roberton Island is one of more than 140 islands in Northland’s Bay of Islands. (Ruth Lawton/Getty Images)

New Zealand’s northern jewel

Most of New Zealand’s visitors land in Auckland and eventually head south. Follow that herd and you’ll miss out on Northland.

The aptly named region is on the tip of the country’s North Island on a peninsula separating the Pacific Ocean from the Tasman Sea.

The region’s Maori meeting houses and historic churches stand as evidence of New Zealand’s early roots and cultural contrasts. The first European settlements started in Northland, and modern New Zealand was born here nearly 175 years ago with an agreement between Great Britain and the indigenous Maori.

It’s also an aquatic playground.

For spectacular scuba diving and one of the world’s largest sea caves, arrange a trip to the Poor Knights Islands, a marine reserve about 14 miles off the east coast near Tutukaka.

North of Poor Knights along the east coast, the stunning Bay of Islands is the region’s biggest draw, where more than 140 rocky islands are sprinkled in waters ideal for cruising, diving, dolphin watching and fishing. American author Zane Grey dubbed Bay of Islands “the Angler’s Eldorado” in the 1920s.

The islands themselves are undeveloped, so stay on the mainland in Paihia or Russell and book excursions on the water from there.

Close to Paihia is the site of the historic 1840 signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, which allowed Britain to annex the North Island and outlined protections to Maori rights. While considered New Zealand’s founding document, the agreement is still a source of tension.

At the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, Maori performances feature a traditional welcome outside and songs and dance inside an elaborately carved meeting house.

North of the popular Bay of Islands, the region gets quieter.

At the top of Northland, venture out to the lighthouse at Cape Reinga, where you can see the unsettled surf where the Pacific Ocean meets the Tasman Sea.

Cape Reinga is New Zealand's most spiritually significant place for Maori. Spirits of the dead are believed to depart here for the afterlife.

The spirits arrive at the cape via the desolate expanse of Ninety Mile Beach (which is actually closer to 60 miles long), which stretches along the western side of Northland’s crowning peninsula.

Farther south along the west coast, giant native kauri trees stand proud in Northland’s largest remaining forests. In Waipoua Forest, Tane Mahuta (“Lord of the Forest”) towers nearly 170 feet tall and holds the title of New Zealand’s largest tree.

Nearby, the older Te Matua Ngahere (“Father of the Forest”) comes in second. At more than 2,000 years old, he’s shorter but with a much wider, more imposing trunk.

Ancient sentinels surveying a majestic land.

The Cape Reinga Lighthouse overlooks where the Tasman Sea meets the Pacific. (Getty Images)

The International Space Station orbits Earth at about 17,000 miles per hour. (NASA)

An uncharted adventure

If you’re astronomically daring, kiss this planet goodbye and soar toward space.

You’ll need to muster a lot of bravery and money. Part of a space tourist’s bragging rights is undoubtedly the financial leap.

Space Adventures has sent seven tourists to the International Space Station.

A $50 million round-trip ticket includes about 10 days at this laboratory that floats about 220 miles above Earth. Here, you can take in galactic scenery while the professional astronauts do their thing.

You'll be able to get spectacular views of land and sea from the ISS and might even catch the fiery fluorescent green of an aurora borealis as the station orbits.

Space Adventures also is planning to take two private citizens to fly by the far side of the moon in 2017 or 2018, says company president Tom Shelley. Price tag: $150 million.

Private space explorers have had to hitch a ride on a Russian Soyuz since NASA canceled its shuttle program. But plenty of space vehicles are in development for private use.

For instance, Boeing recently unveiled a new design for the interior of its future CST-100 manned space capsule. The capsule would take up to seven people to low Earth orbit, including the International Space Station. Bigelow Aerospace is developing a space station for spacefarers to visit, too.

Virgin Galactic hopes to have the first official launch of its SpaceShipTwo by the end of 2014. At $250,000 per ticket, the company has attracted about 700 customers so far.

Departing from the Mojave Air and Space Port, a custom-designed carrier aircraft lifts SpaceShipTwo up to heights around 46,000 feet (8.7 miles), at which point the carrier releases the spacecraft and the rocket motor ignites. The spaceship then accelerates to supersonic speed and climbs even higher.

The most recent test flight took two pilots up to 71,000 feet, the highest yet for this spaceship. Commercial passengers will be up and down in about two hours, Virgin Galactic says.

Meanwhile, XCOR Aerospace is developing a suborbital space plane that it hopes to use for rides up to 330,000 feet. Bookings start at $95,000.

More affordably, World View plans to offer $75,000 rides that rise above 99% of the atmosphere – enough to see the blackness of space and the Earth's curvature, says CEO Jane Poynter.

The company hopes to take its first passengers around the end of 2016, but they are still building a spacecraft.

The World View ride will be all about luxury and comfort, Poynter says noting, "What's a self-respective spaceship without a bar?"

If all of these companies follow through, space tourism will boom. But first it has to take off.

U.S. businessman Dennis Tito became the world's first paying space tourist in 2001. (Alexander Nemenov/AFP/Getty Images)