Taken: The coldest case ever solved

Written by Ann O'Neill • Video by Brandon Ancil • Photographs by Jessica Koscielniak

Chapter 5 — The whole truth?

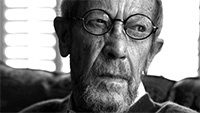

Jack McCullough returned to Sycamore in handcuffs on July 27, 2011 — the same day authorities brought Maria Ridulph up out of the ground. He was an old man, stooped, with white hair, thick spectacles and a long surgical scar from a quadruple bypass snaking down his chest. She was tiny, caught in time at age 7, all mummified skin and bones.

Police and prosecutors gathered at Sycamore's historic Elmwood Cemetery as dawn broke on a glorious summer morning. The Ridulph family plot was tucked in a back corner, in the shade of a majestic elm tree much like the one Maria once played under.

A backhoe stood at the ready. State police investigator Brion Hanley waited on the sidelines with prosecutors Clay Campbell and Julie Trevarthen, watching in awed silence. All felt a powerful connection to Maria.

Trevarthen, who had gotten the Ridulph family's blessing to exhume Maria so her remains could be searched for traces of DNA, saw an overwhelming irony in the timing of events: Maria would rise up on "the same day the S.O.B came back to Sycamore."

Hanley felt it, too. The slain second-grader had been the central focus of his life for three years as his own children circled their 7th birthdays. He would leave the news conferences and photo ops to others as he remained by Maria's side. They could handle the living. He stood vigil for the dead.

An unearthly stench accompanied Maria out of her grave. She had not been embalmed in 1958 because her body had been exposed to the elements for so long before it was found. Instead, the funeral home sprinkled lime on her remains. Her little white coffin was taken from the cemetery to the coroner's office in the basement of the building that also houses the jail.

Prosecutors, investigators and forensics experts filled every inch of the small room. Campbell, a short man, climbed on top of a table in the back corner to get a better view. Trevarthen pushed her way toward the front, and when they opened the casket she thought at first that she was looking at a doll.

One foot was mummified, and they could see Maria's hair and wizened muscles. In a corner of the coffin, a jar held her jaw and teeth; Maria had been identified through her dental records.

No DNA was recovered. But at last, they would learn the cause of death — something the crude autopsy and coroner's inquest had not accomplished in 1958. Maria was stabbed to death.

Krista Latham, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Indianapolis, pointed out nicks made by a sharp blade in the child's sternum and the vertebrae of her neck. Someone had plunged a long, sharp knife into Maria's throat and slashed downward – at least three times.

The man police and prosecutors held responsible was on his way to the Sycamore jail. As he was driven through town, Jack McCullough pointed out his childhood home — and Maria's. He said nothing as they passed through the intersection at Archie Place and Center Cross Street, the place where "Johnny" grabbed Maria.

While the grim work in the morgue continued, Campbell stepped outside for a break. A fierce storm approached from the west, complete with glowering clouds and wind gusts strong enough to knock a man down. He watched it arrive with breathtaking fury in a moment that felt epic to Campbell, perhaps even biblical.

Trevarthen likes to think that Maria had a special greeting for McCullough as he arrived at the jail.

Though the air-conditioned morgue is in the basement, the stench of Maria's corpse traveled through the air ducts and permeated the building for days. The prosecutor hopes it haunted McCullough in his cell.

'All I need is one juror'

The suspect seemed anything but haunted during his extradition from Seattle to Sycamore. He acted more like a kid on a field trip.

McCullough got the window seat in the last row of the early morning United Airlines flight to Chicago. He talked a blue streak, and it didn't take long for other passengers to realize a murder suspect was onboard.

By then, he had read the affidavit police submitted for his arrest, and learned some details of the case against him. He altered his claims about his movements on December 3, 1957, the night Maria was snatched.

He knew they had an unused train ticket to Chicago, so now he said he hadn't taken the train. He'd hitchhiked. He no longer said his father picked him up in Rockford, either; he thumbed his way home.

Was McCullough changing his story so his alibi would match the facts unearthed in the investigation? Or had reading the affidavit genuinely refreshed his memory?

The Seattle cops escorting McCullough had seen it all before. Cloyd Steiger had 32 years on the force. His former partner on homicide, Mike Ciesynski, was now the department's one-man cold-case squad.

Ciesynski had the center seat, next to their prisoner. At one point, McCullough pointed his finger in the detective's face. "All I need to do to beat this case is convince one juror," he said, "like Casey Anthony did. All I need is one juror."

He talked about Maria's beauty, as he had during his interrogation, comparing her to "a little Barbie doll." His voice took on an almost sensual quality. It gave Steiger the creeps.

When their plane touched down in Chicago, local cops and Illinois State Police took McCullough off the plane and loaded him into an SUV. Ciesynski and Steiger rode with him as the motorcade pulled out of O'Hare International Airport and headed toward Sycamore.

McCullough kept up his rant about how he could beat this rap. "Pay attention to the timeline, pay attention to how long it takes to get from Chicago to Sycamore because it's very important," he told the cops. He believed the timeline would prove his innocence.

With decades of experience interviewing murder suspects, Steiger felt like he was being hustled by a sociopath with a constantly shifting story. The detective stroked McCullough's ego, hoping for the big reveal, but it never came.

"He's a weird guy. He's a slammin' narcissist, there's no question about that," Steiger said later. "He's smarter than everybody in the place."

Their motorcade stopped for lunch at a Steak 'n Shake and McCullough gobbled down a hamburger, fries and a glass of milk. He also kept talking. Steiger parked himself at a table behind the prisoner and wrote down everything he said — on a paper placemat.

The Sycamore that McCullough was coming home to wasn't the Mayberry he remembered. It had grown from 7,000 residents to 17,000 in the years he'd been gone. While the downtown area still boasted brick storefronts and tree-lined streets, the country roads were now cluttered with strip malls and fast-food joints. As they rode through town, McCullough pointed out the lot where he'd bought the car that had been his pride and joy.

The Seattle cops finally felt they had heard enough from their prisoner. They signaled to their driver to head to the jail.

As they approached the back entrance, they spotted a line of television satellite trucks. Reporters and camera operators closed in on the SUV.

His wrists were shackled to a waist chain, but McCullough smiled and tried to wave.

"They're all here for me!" he exclaimed.

A jury of one

Sex has always been an underlying theme in this case, and McCullough would face a rape trial before he'd be tried for the murder of Maria. During the investigation, his half sister, Jeanne, told police that her brother raped her and shared her with two friends when she was 14. The attack occurred, she said, at a house near Elmwood Cemetery in 1961 or 1962, while he was between stints in the military.

The statute of limitations should have expired long ago. But McCullough, who was then known as John Tessier, had spent so little time in Illinois that the clock had stopped ticking.

Prosecutors felt the rape case against McCullough was stronger than the murder case. Their witness was impressive.

Jeanne Tessier held advanced degrees from prestigious universities, taught college classes and counseled the parents of terminally ill children. She was 64, a woman of profound faith who never went anywhere without her dog, Spirit. She wore her snow-white hair in a long braid down her back and dressed in flowing, patterned tops and scarves.

Jeanne took the witness stand when the rape trial began in April 2012, and she was followed by a woman flown in from Tacoma, Washington. Michelle Weinman was just 15 when she told authorities in 1982 that John Tessier had sexually assaulted her. He was a Milton, Washington, police officer then and charged with statutory rape. He was able to plead the case down to a misdemeanor, but it ended his career.

With Weinman as their witness, prosecutors would argue that McCullough had a history of taking advantage of girls.

The defense attorneys had made a strategic decision to try the case before a judge instead of a jury. A judge would focus on the legal issues and problems with evidence in a case this old, they thought, while jurors might be swayed by their emotions.

Indeed, Judge Robbin Stuckert had serious questions. Why did the accuser wait decades to mention the crime?

Prosecutors were frustrated that they couldn't explain that the rape allegations surfaced during a murder investigation. Any mention of murder would be prejudicial. Jeanne had dealt with her trauma her own way, and talked about the abuse to police only because they were looking into the Ridulph case. She didn't want to file charges but agreed to go along if it would help the investigation.

The judge also questioned why there were so many holes in Jeanne's story, so many contradictions. Did the attack occur during the summer or the winter? Why could no one else remember the red convertible she said her brother drove? Why did Jeanne remember being dragged down a hallway when the bungalow where the attack allegedly occurred had none?

The judge acquitted McCullough and excoriated prosecutors.

Campbell in turn blasted the judge on the courthouse steps. He said the verdict was a "miscarriage of justice," and called Stuckert's criticism of his office "a travesty."

Jeanne Tessier, meanwhile, unloaded on Campbell in a signed letter published by the local newspaper.

She said she felt like she'd been victimized a second time.

Hearsay rulings: 'I'm toast'

Jack McCullough was so pleased with the outcome of his rape trial that he wanted Judge Stuckert to decide the murder case as well. Forget about a jury of his peers. He viewed Stuckert as "brilliant" and thought he'd found a friend on the bench.

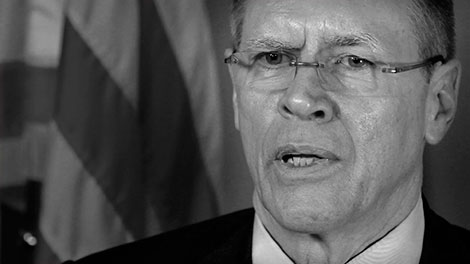

But the judge's war of words with Campbell after her verdict led Stuckert to step down from the murder trial. Judge James C. Hallock was brought in from neighboring Kane County.

Hallock, an associate judge who over the past decade had mostly presided over family court, traffic and drunken-driving cases, was considered a promising jurist but had little experience trying murder cases. As a lawyer, his civil practice had focused on landlord-tenant disputes and foreclosures.

He told the attorneys he had heard some talk about the Ridulph case around the Kane County Courthouse but wouldn't let it affect his decisions.

Before the trial began, Hallock made two key rulings. Both dealt with hearsay evidence.

Two types of testimony are presented at trial. Direct testimony is what witnesses saw and heard with their own eyes and ears. Hearsay testimony is what someone else told them they saw or heard. Because the accused has a right to confront witnesses through cross-examination, hearsay testimony generally is not permitted. But there are certain exceptions, especially when witnesses have died.

The Ridulph case had been reopened because of a statement made by McCullough's dying mother in 1994. Nearly four decades after Maria's kidnapping, Eileen Tessier told her daughter Janet: Those two little girls, and the one that disappeared, John did it.

Prosecutors successfully argued that this statement qualified for a hearsay exception. Eileen Tessier could have been exposed to criminal charges for covering for her son. Her deathbed statement, prosecutors argued, was made "against her own interests."

Hallock said he would allow Janet Tessier to testify about what her mother told her on her deathbed; he'd decide later how much weight to give the statement.

The judge also ruled on a hearsay exception sought by McCullough's defense attorneys. They wanted the 1957 FBI reports on the case allowed in as evidence. The documents, they argued, were key to their client's alibi.

Illinois does not allow police reports, including FBI reports, to take the place of testimony from actual witnesses. Usually the authors of the reports – the cops and investigators themselves — are put on the stand. But in this case, all the FBI agents who'd been involved were dead.

The reports show that Tessier had once been a suspect in the kidnapping but was cleared after FBI agents gave him a lie-detector test. Then 18, Tessier claimed he was 40 miles away, trying to enlist in the Air Force, at the time Maria was snatched from the street corner. His parents, and recruiters in Chicago and Rockford, verified his whereabouts: He was in Chicago in the morning, and in Rockford at about 7:15 p.m.

The defense argued that the hearsay rule barring the police reports is meant to protect the defendant; in this case, the defense wanted the reports admitted. And, if the judge rejected that request, they argued, the reports could come in as historic records because they were more than 20 years old.

Hallock rejected both arguments. The FBI reports would not be admitted as evidence.

There was, however, another way for the alibi to be heard: The defendant could take the stand and testify to what he told the FBI about his whereabouts on the afternoon and early evening of December 3, 1957. But this option was a potentially dangerous move for a defendant who had told conflicting stories during his police interrogation and displayed such an odd demeanor at times. Even his defense team acknowledged that McCullough could be his own worst enemy on the stand.

He would be open to cross-examination by prosecutors, who could ask him about strange details noticed by an Air Force recruiter the day after the kidnapping:

How did he get that cut on his lip?

Why did he bring up the kidnapping that had occurred in his hometown?

And why did he show off a little black book with the names, addresses and measurements of girls in Sycamore?

The hearsay rulings seemed one-sided to the defense, and the outcome felt inevitable to McCullough:

"As soon as the judge ruled this stuff wouldn't be admitted I knew: 'Oh man, I'm toast.'"

Staring down 'Johnny'

Kathy Sigman Chapman found it unnerving to come face to face with "Johnny" after all those years. She couldn't take her eyes off the defendant as she testified during his trial in September 2012. He stared right back at her.

He seemed to Kathy to be smirking, like he was sure he would beat the charges.

She was resolute on the witness stand as she recounted the story she'd told so many times before – how she played "duck the cars" with her best friend Maria, how a friendly stranger who called himself Johnny offered them piggyback rides. She recounted how Maria and Johnny were gone when she returned from a quick trip home to fetch her mittens. She was shown an old newspaper photograph of herself as a child, displaying those mittens.

"My goodness," she said.

Kathy stood her ground when she was shown the same six photos of suspects she'd seen in 2010. She was firm in her conviction that she had identified the right person and without hesitation went straight to the fourth picture from the left.

"This photo right there," she said, tapping the picture of John Tessier.

On cross-examination, McCullough's defense attorney pointed out that Tessier's photo differed from the others. But he couldn't shake Kathy.

"That picture was slightly different than other pictures, is it not – is that fair to say?" he asked.

"No. It was the picture of Johnny," she said.

Eventually, Kathy acknowledged that the young man in the photo she chose wasn't wearing a suit as the others were. And she agreed that the background in his photo was darker.

But, she insisted, it didn't matter.

"I wasn't looking at background." She said she focused on the man's features.

Janet Tessier testified about her mother's dramatic deathbed statement, recounting the story in straightforward fashion, without drama or embellishment. Asked why she didn't prod her mother for more details, she responded that she was reacting as a daughter, not an investigator.

The defense countered with its own witness, Janet's sister, Mary Hunt, who'd also been at her mother's side when she was dying. Hunt reluctantly testified that she heard her mother say only, "He did it."

She could not say who "he" was, or what "it" was.

Informants from Cellblock G

Three jailhouse snitches who came forward – two of them just days before the trial — testified about conversations they had with McCullough at the DeKalb County Jail. They all said he admitted killing Maria.

But each gave a slightly different account of the killing, and all said Maria died by strangling or suffocation. They didn't name the cause of death determined by a forensic anthropologist: stabbing.

Jailhouse snitches are notoriously unreliable. They are criminals, or at least accused of crimes, so their credibility is suspect. Most inmates who offer testimony are looking to cut a deal for themselves by hanging someone else out to dry.

Kirk Swaggerty, Christopher Diaz and a third inmate who testified under the pseudonym "John Doe" had been locked up with McCullough on Cellblock G.

Swaggerty was the first to provide information. He wrote a letter to the state's attorney's office. His motive, he said, was to do the right thing. But he'd been convicted of a home invasion murder, and he also was asking the court for a reduction in his 33-year sentence. He said he'd been promised nothing. Whether he expected something was another issue.

McCullough admitted he had killed Ridulph, Swaggerty testified, but claimed it was an accident. He explained that Maria fell during the piggyback ride. "She wouldn't stop screaming and he was trying to keep her quiet and she suffocated."

He also heard a story McCullough volunteered during his police interrogation, and later in his interview with CNN: "He said that he had called the FBI himself because he had a dream that a guy named Johnny did this to the girl and that the guy Johnny lived a few houses away from the little girl."

But if Swaggerty is to be believed, McCullough took that story a step further:

"He then told me he was Johnny."

The other two inmates shared a cell. They said they came forward when McCullough told them he was looking for someone to kill Swaggerty because he was a "snitch."

Diaz was in custody on an immigration hold after being accused of having sex with a 14-year-old girl. He testified that he turned down the volume on his headphones as McCullough walked into his cell and started talking about his case: "He was saying about how he was giving the little girl, the victim, a piggyback ride and he – he ran with her down this alley once the other girl that was there went inside the house to grab the mittens." McCullough returned the next day and talked some more. That time, Diaz testified, he said he strangled the little girl with a wire.

(McCullough insists that he was talking about the contents of an anonymous confession letter sent to Maria's father in 1964. The details in the letter do match this version of the killing.)

"Doe," another convicted home invasion killer, testified that McCullough told him he slipped while giving the child a piggyback ride. "The little girl hit her head and started crying or yelling … He said it was an accident."

Then McCullough said he carried the child inside his house and choked her, "Doe" testified. Later, he said, McCullough changed his story, saying he "strangled her with a wire."

Doe also picked up on McCullough's odd demeanor when he spoke of Maria, just as investigators had. "He would seem almost childlike. He would get real giddy, if that's the right word. It's like he couldn't stop himself. He would just keep going and going. When he was talking about the little girl, he would get amped up."

Testimony lasted all of four days. McCullough did not take the stand, so his alibi was never presented.

Besides the excluded FBI reports, there were other missing pieces at the trial. The unused train ticket from Rockford to Chicago didn't come into evidence, nor did the video of his eight-hour police interrogation. That evidence didn't really prove anything, other than to cast doubt on his credibility, and by remaining silent he didn't call his credibility into question.

When it came time for the verdict, Judge Hallock said he believed the informants and found Kathy Chapman's testimony particularly convincing. He didn't say a word about what Eileen Tessier told her daughters on her deathbed.

A loud cheer erupted as the judge handed down the verdict – guilty on all counts: murder, kidnapping and abduction of an infant.

Johnny was going to prison. Kathy was finally free.

"If I would have been shown his picture in 1957," she said, " he would not have been a free man all those years. He would have been in jail."

At a news conference, Janet Tessier told Maria's siblings she was sorry – sorry that her brother killed Maria, and sorry it had taken so long for the truth to be told.

She apologized on behalf of her mother.

Jaded cops had tears in their eyes. Justice was Maria's at last.

Prison life

McCullough is 73, and prison life isn't easy. He spends most of his time alone. He is kept in protective custody because he qualifies twice as the lowest form of life in prison culture: He's a convicted child killer and an ex-cop.

He spoke for several hours with CNN while at the state's maximum-security prison in Menard, before being moved to another prison in Pontiac, most likely because of his age and notoriety. Menard, a 19th century brick behemoth, overlooks the Mississippi River in southern Illinois, about an hour's drive from St. Louis, Missouri.

McCullough announced his innocence without prompting as he sat down and was shackled to a metal table: "I've been accused and convicted of a murder I did not commit." He said it twice.

He seemed happy to have visitors. He likes to talk, especially about himself. He broke into tears when asked about his combat experience in Vietnam, but showed little emotion as he spoke about the murder in his hometown. His explanation: "I was part of one, but not the other."

He tried to steer the conversation away from questions about Jeanne, the sister who accused him of rape, and his acquittal in that case. "We have a history," he said of his sister. He used the same expression to describe the relationship between his mother and her father, who he believes sexually abused her.

He spoke about his mother as if she were a saint and called Janet, the sister who launched the murder investigation, "a black sheep" and a liar. He responded with a non sequitur when asked: If he were innocent, why would so many people tell lies about him in court? "Exactly."

He wouldn't discuss the nude photograph of his 12-year-old daughter that an ex-wife said she found hidden under a drawer. He said his daughter was troubled and had problems with men, drugs and alcohol.

He said he regretted taking in the teen runaway Michelle Weinman when he was a police officer and says she "set me up."

"I was accused of rape, and it didn't happen."

By the time of CNN's interview, he had come to recognize that others found it strange that he referred to 7-year-old Maria Ridulph as "lovely, lovely, lovely." He changed his wording, calling her "precious." An odd expression crossed his face when he spoke of the little girl with the dark, curly hair and big brown eyes.

There is a gap between his front teeth and he does have a high, thin voice, just as Kathy described all those years ago. He is quick to anger over certain subjects and, when that happens, there is nothing soft in his blue eyes.

The women left behind

Unlike many destined to end their days behind bars, Jack McCullough has not been forgotten. His wife of nearly 20 years, Sue McCullough, and a stepdaughter, Janey O'Connor, wrote letters to the court saying they stood by him. Both are certain that he is the victim of a grave injustice.

Their letters were more articulate than many written on behalf of men judged guilty of heinous crimes. Sue scolded the authorities in Illinois: "My husband was convicted in order to close the oldest cold case in U.S. history. You should all be ashamed of yourselves." And the hurt in O'Connor's words was unmistakable: "Perhaps sacrificing one old man is enough to give an entire community closure," she wrote. "My Dad is innocent. I hope the pain of my family is worth the five minutes of fame you all have received."

O'Connor, 35, says she trusted McCullough with her own daughter, and he doted on the child. When police came to arrest Jack, the little girl was watching cartoons in his bedroom.

O'Connor has assumed the role of her stepfather's spokesman and champion. When she first met him, she says, she was a wild kid – exactly the type of teenager he has been accused of preying upon. It would have been so easy for him to cross the line with her, she said. But he never did.

Instead, McCullough was patient. He became the father she never had. She believes now it is her turn to watch out for him.

O'Connor does not rant. She is logical in her arguments. She doesn't understand why the court didn't let her stepfather defend himself better.

She doubts how much Kathy Chapman can remember about that night long ago. It was dark, it was snowing, and Kathy was just 8.

O'Connor points out that Chapman picked out another man she said resembled the kidnapper at a lineup in Wisconsin back in 1957. It turned out he couldn't have been "Johnny;" he had an alibi.

The timeline bothers her, too. The time of the kidnapping has shifted from 7 p.m. back to about 6. It also troubles her that the defense couldn't present evidence of a collect phone call placed from Rockford to the Tessier family house at 6:57 p.m. — or anything from the 1957 FBI reports that once cleared him as a suspect.

And she absolutely does not believe the stories told by the Tessier sisters. She wonders whether her stepfather, as the first-born in his family and his mother's clear favorite, wasn't targeted by the others out of some twisted sibling rivalry.

There's a blog now, where the family raises questions about the evidence used to convict McCullough. His stepdaughter hopes someone will notice and take up his cause, as others have done in famous controversial cases such as the West Memphis Three.

Sue McCullough also is standing by her man. She acts at times like this mess is all a big misunderstanding, and he'll come home soon.

She passes the time in a rickety chair in the bedroom of their small apartment in Seattle. There isn't much furniture, just a few chairs, a bed and a home computer. A large safe dominates the living room, her husband's Stetson hat resting on top.

She has visited him in prison, and says he seems frail. She treasures a letter he wrote a few months after his arrest. She had it laminated and keeps it close:

"Hang on because I'm going to not only apologize, I'm going to say I'm sorry. (My pen didn't want to write that but my heart did.) I do need to say I'm sorry for all the times I disappointed you, made you mad, made you sad, yelled at you or just pissed you off," the letter begins.

What is he apologizing for? Nothing specific, she says.

"He just wanted me to know he's going to treat me better when he comes home."

A perfect alibi?

A criminal trial is a journey to the truth, or so goes the conventional wisdom. Witnesses are sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. But the whole truth is rarely told at trials; they are more like well-scripted plays, edited in advance through a series of pretrial legal maneuvers and evidentiary rulings.

The prosecution's version of the truth was told last fall at McCullough's four-day murder trial. The defense consisted of an anemic attempt to poke a few holes in the prosecution's script.

"Based on the judge's pretrial rulings, it became a situation in which we sort of tried the case with our hands tied behind our back," said his lawyer, Public Defender Tom McCulloch.

The defense attorney could not show that the FBI had cleared his client decades ago. Without putting his client on the stand, he could not present an alibi defense. He could not tell Jack McCullough's version of the truth. Nor could he argue that Kathy Chapman had picked out someone else in the Wisconsin lineup back in 1957. Because she could not recall the lineup on the witness stand, he couldn't question her about it.

Had the crime been committed a year or two ago, there likely would have been DNA samples to test, along with credit card receipts, phone records and cellphone GPS pings to trace. There would have been little doubt where McCullough was – and when. The key witnesses would be alive and their memories would be fresh.

But this 55-year-old kidnapping and murder suffered from weaknesses typical of cold cases: The physical evidence that had existed was lost, including the doll Maria was carrying and her killer handled. No murder weapon was found. Most of the witnesses were dead.

"When it came down to our case and the state's attorney's case," said defense investigator Crystal Harrolle, "the state had more people alive than we did."

Prosecutors and defense attorneys were left to reconstruct history with what little evidence they had. And that is why a decision to bar any surviving evidence – even old police reports – can be so significant in a cold case.

Judge James Hallock ruled before the trial that Eileen Tessier's dying statement implicating her son would be admitted, but the 1957 FBI reports would be barred. As a result, a mother was able to accuse her son from the grave, but his alibi was never heard.

Would justice have been better served by a hearing of all of the facts and theories?

"I think the question of how you deal with old reports that are as authentic as the day is long — in the context of them being the sole remaining evidence of a defendant's alibi — is something an appellate case will have to decide," said McCulloch, the defense attorney.

Hallock could not comment on his rulings. Judge Judith Brawka, the chief judge of his circuit, cited McCullough's appeal and said in an e-mail that the state's code of judicial conduct "prohibits a judge from public comment about a pending proceeding in any court."

CNN consulted two attorneys with expertise on Illinois' hearsay law. Both were intimately involved in the Drew Peterson case, which galvanized the sweeping changes to the law in 2008.

Steve Greenberg was a member of Peterson's defense team. Stephen White, at the time a judge, upheld the constitutionality of what became known as Drew's Law. It expanded the circumstances under which hearsay statements could be admitted in trials.

Peterson, a former police sergeant in Bolingbrook, Illinois, was convicted in 2012 of killing his third wife, Kathleen Savio; he is suspected of killing his fourth wife, Stacy Peterson, who vanished in 2007.

In Peterson's trial, the new hearsay exceptions allowed statements both women made to others that Peterson might harm them. Why? The women were unavailable to testify, and a judge found that Peterson likely was responsible for their absence.

Examining the Ridulph case for CNN, both Greenberg and White questioned how Eileen Tessier's deathbed statement could have been allowed into evidence. Drew's Law didn't apply because the defendant did not make the witness unavailable; she died of cancer.

Judge Hallock admitted the woman's dying words under the theory that she made the statement "against her own interests." But CNN's experts pointed out that she admitted no wrongdoing, so it really didn't fit under that hearsay exception.

Eileen Tessier never acknowledged taking part in a cover-up. She merely said, "John did it," or "He did it."

"It's an accusation," Greenberg said, not a confession. "If she had said 'John killed that little girl and I helped him cover it up,' that would work. But this is too sketchy."

In Greenberg's view, allowing in the deathbed statement was a stretch of the hearsay exception. And it raises a question: Should the court have taken a similarly liberal view toward the defense's request for a hearsay exception? Should it have also allowed the old FBI reports?

Greenberg says the FBI reports might have come into evidence as historical records – a hearsay exception that applies to documents that are more than 20 years old. That was the defense's strategy, but the judge rejected it. The exception has been used in the past for maps, deeds, wills and other civil documents, but never for police reports. There is no legal precedent to allow them.

But every legal precedent begins with a test case, Greenberg added.

Campbell, the prosecutor, said he was "stunned" that Hallock allowed Eileen Tessier's statement into the trial. But, because the judge did not cite it in his verdict, Campbell believes the error might be "harmless" – not enough to overturn the conviction.

Campbell said that he thought Hallock's ruling on the FBI reports was solid; he can't see any circumstance under which a judge would allow police reports into evidence in the place of witness testimony. Had the FBI reports been allowed, he said, prosecutors were ready to fight back by showing that the original source for the alibi was the defendant himself.

If the FBI reports were to somehow enter the case, there are two timelines to consider, not just one. And that really is the central dispute in this cold case: Was Maria snatched at 7 p.m., or did the crime take place earlier, before 6:20?

Newspaper articles from the time — and the FBI reports themselves — show that establishing a clear timeline was a problem from the very first hours of this case. Only two facts relating to the timeline cannot be disputed: A collect call was placed from Rockford, 40 miles away, to the Tessier family's house at 6:57 p.m. And Maria wasn't reported missing to police until 8:10 p.m.

So what happened at the corner of Center Cross Street and Archie Place between 6 and 8 p.m. on December 3, 1957? The police and FBI reports from 1957 could have helped shed light. CNN was able to examine about 200 pages of those reports; thousands of pages more remain sealed from public view.

If Maria was snatched at about 7 p.m., the defense says, John Tessier couldn't have been the kidnapper. He was 40 miles away, in Rockford, calling home from a pay phone.

That was the conclusion the FBI agents in Sycamore reached in 1957, when they cleared Tessier. A judge or jury might have reached the same conclusion, defense attorney McCulloch believes, had the old FBI reports been admitted at the trial.

"The FBI verified all of that information," he said. "So if you are 40 miles away at that point, roughly three minutes, give or take, away from the time of the snatch, that is what we believe to be the perfect alibi."

Eyewitnesses and snitches

Appeals courts are unpredictable, lawyers say, and might sidestep the tricky hearsay questions if one or more other issues appear problematic.

Other vulnerable areas, according to former judge Stephen White, include the credibility of the jailhouse informants and the reliability of the eyewitness identification. These two issues have caused many a conviction to fall.

Testimony from informants has played a role in 15% of the convictions overturned nationwide by DNA evidence, according to the Innocence Project. In a 2005 study, Northwestern University Law School's Center on Wrongful Convictions documented 38 cases in which informant testimony sent innocent men to death row.

The issue with informants is partly one of motive. Why are they testifying? Street informants often are seeking financial rewards or trying to avoid arrest. Jailhouse informants usually are motivated by a reduction in sentence or other special favors.

Prosecutors are not permitted to offer inmates favors in exchange for testimony. But in this case, one inmate mentioned his assistance in the McCullough case in court papers seeking a reduction in his sentence. And another did receive what the defense contends was favorable treatment: He was allowed to testify anonymously as "John Doe." His name, his record and other details about his background remain sealed from the public record.

Campbell said he found the jailhouse informants credible because they told three different stories about how Maria died. Police couldn't have planted the stories the inmates told.

"What you get from this is there was no effort by us to go over there and hang out some cheese, and so whoever gives us the story gets the cheese," he said.

Faulty eyewitness identification is also problematic, according to the Innocence Project. In Illinois, it has played a role in 24 wrongful convictions, cases later exonerated by DNA evidence. Among the factors contributing to misidentification, research shows, is the kind of photo lineup used, and the way it is administered by police.

The defense contends that Kathy Chapman chose McCullough's photo from an "impermissibly suggestive" lineup. His was the only photo with a dark background; he was the only one not wearing a suit; the others looked off to the right, but he stared directly into the camera; the others' hair was combed while his was unruly; the other photos were yearbook photos, his was not.

"The picture of Jack was done differently, no tie and the lighting is different, and that's the one she picked," defense attorney McCulloch said. "It shouldn't be a surprise, but 55 years later maybe people react to subliminal suggestion. If you're looking for 'one of these things is not like the other,' then the answer is pretty clear which photo to pick."

The defense also notes that investigator Hanley spoke with Chapman for about 90 minutes before returning more than a week later to show her the photos.

Unlike Illinois, many states do not allow the same investigator who questions witnesses to show them photographs of suspects. The point is to avoid the natural tendency of witnesses to give the answers they think police want to hear.

Campbell is certain that Jack McCullough killed Maria Ridulph. He is confident in Kathy's Chapman's identification of "Johnny." He and Hanley note that she did not learn she'd chosen McCullough's photo until 10 months later, when he was charged. Campbell believes her when she says she could never forget his face.

"I spent a lot of time with her," he said. "I am familiar with the identification problems, and snitches have taken down clients of mine before. At the end of the day, it's the best system we have."

However problematic they might be, the testimony from the jailhouse informants and Kathy Chapman's eyewitness identification convinced Judge Hallock that McCullough was a child murderer and a kidnapper. He expressed confidence that his decision will be upheld on appeal.

Defense attorney McCulloch and his investigator, Harrolle, remain convinced that their client is innocent.

"I think it was an incredibly thin case," said McCulloch. "It seems to me Illinois has a bad history of having existing prosecutors file sensational cases as they prepare for election."

If Campbell pursued the 55-year-old cold case as a means to re-election, it certainly backfired. The prosecutor lost his job by 700 votes just weeks after the conviction. He will be watching the appeal as a private criminal defense attorney.

He is keenly aware of the questions that swirl around many cases after a conviction – especially a cold case.

"Any type of cold case is going to raise questions, and to be honest with you, I think that's healthy," Campbell says.

He cites a sad truth about the criminal justice system: It is fallible.

"Here in Illinois, we've had a lot of people go on death row who ultimately ended up being innocent," he says. "We're always concerned about people being convicted of crimes they didn't commit."

'Look in the box'

Jack McCullough finally got his say at his sentencing. He stood before the court last December 10 — 55 years and seven days after Maria Ridulph disappeared.

He used the occasion to tell his version of the truth. He insisted that he didn't kill Maria, and that the FBI had cleared him. He blamed his legal predicament on ambitious cops, corrupt prosecutors, an incompetent judge and spiteful siblings. He challenged Kathy Chapman's ability to remember a face after 55 years.

He accused the judge of ignoring the FBI reports and his alibi. "Look inside the box," he exhorted, pointing to a carton labeled "McCullough case" resting on the defense table. "The truth is in the box."

He was defiant to the end. His remarks to his probation officer were read aloud at his sentencing. Asked what caused him stress, he had said: "Corruption, Democrats, socialism, rude people, noisy people, black people and Muslims."

Maria's siblings did not stand up in court and speak. They chose instead to write letters, which were slipped into the court file. The sad, simple beauty of their words bore stark contrast to the ugliness of McCullough's.

Chuck Ridulph wrote about the crime that defined his life, and the little sister he never got to know. As his parents neared the end of their lives, he said, they both couldn't wait to be with Maria. They are buried next to her at Elmwood Cemetery.

He wonders often about the woman Maria would have become. "Would she have excelled at music?" he asked. "How would I have scrutinized her first boyfriend? Where would she have gone to college? Who would she have married? How many children would she have had? What fun would we have had together? The answer to all those questions, and so many more, Jack McCullough snatched away."

Snow began to fall as the hearing ended and the key players in this cold case gathered one last time on the front steps of the old courthouse in Sycamore. The meaning was lost on no one: It had been snowing all those years ago when Maria was taken.

Chuck Ridulph felt the hand of God. Kathy Chapman saw her lost friend signaling approval.

Once again, Kathy's hands felt cold. Some things never change; she had left her gloves behind in the car.

She stopped by Maria's grave on her way home from court. She bent down and picked up a small rock with the word "justice" carved into it. She cradled it in her gloved hands as she bowed her head in silence. Asked later what she told Maria, she replied, softly, "Private little things."

After Kathy had gone, seven pennies — one for each year of Maria's life — were lined up on the headstone.