Taken: The coldest case ever solved

Written by Ann O'Neill • Video by Brandon Ancil • Photographs by Jessica Koscielniak

Chapter 4 — 'That's him'

How wonderful it is to be 8 years old at Christmastime. But what if one moment your best friend is there, laughing and cutting out paper snowflakes, and then in an instant she is gone forever?

Imagine what it is like to have grown-ups constantly asking you questions and showing you pictures of strange men. To have flashbulbs going off in your face, leaving spots dancing in your eyes.

Why isn't Maria coming home?

Think for a minute what it is like to be sad for months on end, and to wear your new Easter coat to your best friend's funeral. And then imagine spending your childhood looking over your shoulder for a bogeyman you know is real.

Is he coming back for you, the girl who got away, the one he didn't choose?

You put it all to rest. Life goes on. Half a century passes and then, suddenly, a knock on the door brings it all back again. Fifty-three years later, you're replaying that terrible night all over again.

Imagine all of that, and you get a sense of what it was like to be Kathy Sigman after a man who called himself "Johnny" kidnapped and murdered Maria Ridulph in 1957. Kathy saw "Johnny" give 7-year-old Maria a piggyback ride minutes before she vanished from the street where they lived.

Kathy grew up hearing the whispers: "She's the one who was with Maria."

Some mothers wouldn't let their daughters play with her. Some mothers didn't want their sons to date her. She was different, marked.

No wonder she couldn't wait to get out of Sycamore, Illinois. And so eventually she did, marrying and moving to Texas and Florida and raising three kids before settling in St. Charles, about half an hour away from her hometown.

Knock, knock. A man in his late 30s wearing a football jersey and a turned-around ball cap stood at the door, chewing gum furiously. It was about 6 p.m. on September 1, 2010. He knocked again.

Kathy Sigman Chapman thought the caller was a salesman, so she ignored him. But as he turned to walk away, her husband spotted handcuffs dangling from his back pocket.

Can I help you? Mike Chapman asked, opening the door a crack and peering out.

The man turned and answered: This is about something that happened a long time ago.

Brion Hanley, of the Illinois State Police, wanted to show Kathy some photos. For two years, he'd been piecing together a cold case — rekindling memories, poking holes in an alibi.

It began when a tipster e-mailed state police, saying her mother knew who was responsible for Maria's disappearance and murder: the tipster's half brother, John Tessier. Those two girls, and the one that disappeared, John did it, the dying woman told her daughter. John did it, and you have to tell someone.

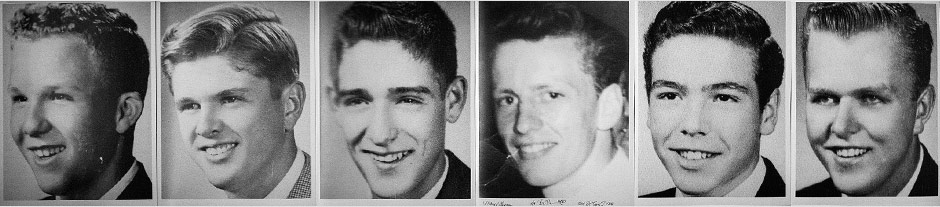

Hanley and his partner, Larry Kot, had compiled a "six-pack" – a composite lineup of six photographs, including one taken of their suspect, John Tessier, at a dance. The detective was eager to show the lineup to Kathy.

But as she spoke of "Johnny," all the details came flooding back – the piggyback ride he gave Maria, the trip Kathy made to fetch her mittens and how she lost her best friend. Kathy felt overwhelmed.

Hanley sensed it was too soon to show her the photographs. He'd only get one chance, and she was too rattled. She needed more time to work through long-buried memories.

More than a week passed before he stopped by to see the Chapmans again. This time, he laid out the six shots, one by one, on the glass-topped coffee table in the couple's living room. Kathy perched on the edge of the sofa, leaning forward as she intently studied each face.

Five of the photos were taken from Sycamore High School's yearbook. John Tessier had been kicked out of school in 10th grade, so his close-up wasn't from the yearbook. It was slightly different. His collar was open and the background was darker.

Kathy eliminated several photos right away, but she continued to pore over two – No. 1 and No. 4. She studied them for a good two minutes; it felt to Hanley like an eternity.

"That's him," she said, tapping No. 4.

Kathy placed her hands over her head and let out a long sigh.

She was certain.

"That's him."

She didn't know whose picture she'd chosen, or if it was the one Hanley was hoping she'd pick. He didn't tell her.

But she had no doubt.

"I couldn't forget that face," she later recalled.

Her mother had instructed her to sear Johnny into her memory:

Remember his face, Kathy, she'd said. You are the only one who can catch him. You are the only one who knows what he looks like.

More than half a century later, Kathy smiled.

"Yeah, Mom, I remember."

'You don't know Jack'

Brion Hanley had what he needed: a bona fide suspect. It was time to go see "Johnny." He knew from his tipster where to find him: Seattle.

If Hanley was relatively new to homicide investigations, the two Seattle cops who joined him on the case were grizzled veterans.

Cloyd Steiger is a jokester who masks the grim work with gallows humor. He keeps a binder of old cases on his desk, titled "My Career in Homicide: My Day Begins When Yours Ends." He has been a Seattle cop for 32 years and could have retired long ago, but he loves the work. His first case on the homicide squad was the murder of an 8-year-old girl. He solved it.

Mike Ciesynski favors tailored suits and wears his hair closely trimmed and brushed back. He's an avid golfer. He keeps a supply of pens on his desk inscribed with gold letters that say, "Knock, knock. Remember a long time ago?" But the pens are more than a gimmick. They're stamped with his phone number.

Seattle's police headquarters is high on a hill downtown, nestled against Interstate 5. The homicide squad looks out over Puget Sound through floor-to-ceiling windows on the 7th floor. There, the cops' desks are arranged in cubicles, and a skull on a stick with the sign "DEATH" signals who will catch the next case.

Around the corner, down the hall from the interrogation rooms, is a windowless closet of an office, Room 762. There's a sign on the door: "Cold Case Squad, NO Dumping."

This is where Ciesynski works. In Seattle, a cold case is defined as any homicide left open after the retirement or departure of the original investigating officers. Ciesynski started with about 300 cases; 30 have been solved.

The Seattle cops learned that Hanley's "person of interest" was living and working in a high rise for seniors, the Four Freedoms House, in northwest Seattle. He was Jack McCullough now, having changed his name in the early 1990s when he married his fourth wife.

He was an ex-cop with a checkered past. Steiger and Ciesynski pulled John Tessier's police personnel file from Milton, Washington, and discovered he'd been a screw-up. They learned about his womanizing ways and how he dabbled in cheesecake photography. They learned he was fired from the police force after being charged with the statutory rape of a 15-year-old runaway.

They tracked down the victim, now in her 40s, and Hanley and the two Seattle cops paid her a visit at the bar where she worked the day shift. As Michelle Weinman told her story, the cops shook their heads. He'd dodged the statutory rape case, pleading guilty to reduced charges and spending a year on probation. He went by John Tessier then.

"You don't know Jack like I knew John," Weinman said.

They searched a storage container McCullough owns on 20 acres outside the tiny town of Tonasket in Okanogan County. The spot is isolated; fewer than 41,000 people live in the entire county.

Inside, the cops found thousands of photos taken by their suspect. Some showed whip-toting women wearing leather bustiers, boots, chains and dog collars. Ciesynski later tracked down a few of the models. They described McCullough as a "letch" who plied them with alcohol during the photo shoots, claiming he was working for artistic magazines.

The cops also talked to his third wife, Denise Trexler, who told them she'd found a creepy photo taped to the bottom of a drawer. It was a nude picture of Jack's 12-year-old daughter from his first marriage. Trexler said she later learned that while she was at work he was taking suggestive photos of the girl and her middle-school friends.

Investigators also discovered that McCullough's daughter, who vanished in 2005 at age 34, near San Antonio, Texas, was listed as "missing endangered." She was last seen at a motel with her boyfriend. Her body, which was found on a golf course shortly after she disappeared, was identified in June 2013. Police have opened a homicide investigation and would not comment on the case.

Hanley still feels a chill when he recalls the daughter's middle name: Marie.

The first Mrs. McCullough

If anything, Jack McCullough seemed to have mellowed since his years as John Tessier. He had been married to the same woman, Sue, for almost two decades. The couple often baby-sat the children of Sue's daughter, Janey O'Connor.

He met Sue through work: He was a driver at her father's limousine service; she was the dispatcher. For 30 years, the company shuttled airline crew members from Sea-Tac Airport to their hotels. It is no longer in business.

When he proposed to Sue in 1993, he told her he was thinking about changing his name.

"Do you want to be the fourth Mrs. Tessier or the first Mrs. McCullough?" he asked. McCullough had been his mother's maiden name, and he said he wanted to honor her.

McCullough didn't talk about his family much; when he did, Sue and Janey sensed there was a powerful sibling rivalry. And no love lost for his sisters.

Before they married, Sue received a strange phone call from McCullough's sister, Jeanne Tessier. Janey, who was a teenager at the time, listened in.

The caller warned that the man Sue planned to marry was "evil" and that her daughter wasn't safe. But she gave no details. The caller never said a word about a kidnapped child.

"She was going on and on, and my mother asked her," "What did he do that was so awful?'

"Jeanne said it was the way he looked at her, the way he made her feel. 'He would touch my hair and tell me I was pretty.'"

Later, the story Jeanne told police would be much darker, and far more specific. It would lead to a rape trial.

'Look at my eyes'

The police came for Jack Daniel McCullough on June 29, 2011. He had just finished his graveyard shift as night watchman at the Four Freedoms House.

Oddly, his apartment number was the same as Maria's street address on Archie Place in Sycamore: 616.

Ciesynski watched McCullough for several days before making his approach. Then, he used a ruse, saying he needed the night watchman's help with an assault in a downtown luxury apartment building where McCullough had worked the previous year. But soon, McCullough was taken on the proverbial ride downtown, to Seattle police headquarters. He was placed in an interrogation room and told they had some questions about the Maria Ridulph case.

Sure, he said, he'd be glad to help.

Hanley read McCullough his rights. "It's all good advice," the suspect said, waving him off. "I'm on your side here. I'm trying to help you."

CNN obtained a copy of the eight-hour interrogation. At first, McCullough seemed gracious, even obsequious. He made small talk and cracked jokes with the officers. But he bristled when Hanley asked about his marriages and divorces: "You're investigating a child, right? You're not investigating me."

During a break, when Ciesynski left the room, McCullough signaled for Hanley to stay with him. He said the others didn't seem interested in what he had to say. He leaned over a tabletop and gestured for Hanley to come closer. "I had a dream," he said, suddenly slapping the table with his palm. "And it reminded me of a conversation I had as a kid." He said a friend warned him to stay away from another boy who was preoccupied with sex. He couldn't recall the name of the boy, but said he stayed with a family in the neighborhood.

He raised his voice, slowed his words and dramatically tapped his fingers on the table top with each word.

"And on the same block as Maria lived."

McCullough squirmed and became evasive when asked about his family and sex. He denied sexually assaulting his sister Jeanne.

"I NEVER HAD SEX!" he roared, pounding the table in the interrogation room.

"Ok, what did you have?" Hanley asked.

"Just playing around."

"O.K., O.K., playing around with your sister. You know that we just want you to be honest," Hanley continued. McCullough countered that even if he did "play around" with his sister, "that doesn't make me a murderer."

Without any prompting, he leaned forward and stated:

"Let me tell you something, I did not kidnap that little girl."

He brought his face close to Hanley's. "Look at my eyes. I did not have anything to do with that little girl. She was loved in the neighborhood. She was a little Mexican girl with big brown eyes and she was sweet as could be, hardly said a word to anybody and everyone loved her."

'Lovely, lovely, lovely'

Nearly three hours into the questioning, McCullough agreed to take a polygraph test but balked when the questions became personal. He alternated between rage and calm before shutting the test down.

Irene Lau, the homicide detective who prepared the test, thought he showed a strange attachment to Maria.

"He described her as being very stunningly beautiful with big brown eyes and he stated that she was 'lovely, lovely, lovely,'" Lau recalled. "He appeared to be discussing her as if he was talking about someone he had been deeply, deeply in love with."

After the aborted polygraph, Ciesynski took over the questioning. The veteran cold case investigator relishes the "bad cop" role in interrogations. He got in McCullough's face, relentlessly challenging him about his whereabouts on December 3, 1957 — the night Maria was kidnapped. He confronted him with the deathbed statement his mother made to his sister.

"The only time Mom talked about it was when I was going to see the FBI," McCullough insisted. "She was crying. I said, 'Don't worry Mom, I'll be cleared.'"

He refused to acknowledge that his mother would say on her deathbed that he killed Maria. "That's a lie! My mother loved me," he protested. "She would never say that."

Ciesynski showed him an unused, military-issued train ticket investigators received from an old girlfriend and pressed him on how he'd gotten around on December 3.

He was at a recruiting station in Chicago the morning of Maria's kidnapping, but his whereabouts between noon and 7:15 p.m. could not be independently verified. If he hadn't taken the train to Chicago, as he'd originally told the FBI, he must have driven his car there, the cops believed. And if that was the case, he could have driven back to Sycamore. He could have been there during the period the cops now suspected Maria was snatched.

McCullough couldn't really explain. Maybe he hitchhiked, he said.

Finally, Ciesynski showed him the lineup photos, laying copies down on the table like playing cards. In the No. 4 spot was the photo of him that Maria's friend Kathy had identified. McCullough avoided looking at it.

"I don't know what you're talking about," he said.

The detective pressed on. "There's no doubt in my mind that you were the person who was there. I'm not saying that you went and killed her. You were there at this time."

McCullough pushed back. "This was two blocks away from my house. Everybody in the neighborhood knew me."

He grew edgy when he was asked whether he ever handled Maria's clothes or touched any of her things. He placed a chair as a barricade between himself and the detective, who decided that it was a good time to leave the suspect alone with his thoughts.

With the cops out of the room, McCullough touched his toes, stretched and pushed the photo of himself away, sliding it across the table. He sighed and studied his image in the reflective glass of a one-way window. He looked at the photo again, and back at his reflection. Then he studied the photo some more.

As the clock struck midnight, he leaned back in his chair, pursed his lips and made a raspberry sound. He said, to no one in particular, "Not a very good picture." He looked at it again, leaned back and let out a long, loud belch.

"OK, that's me," he conceded when Ciesynski returned a few minutes later.

"This is a very poor picture. I didn't even recognize myself." He said that the boy in the photo looked "too effeminate."

He was shown the full photograph, taken on a date with a girlfriend, Jan Edwards, on June 22, 1957. "I was in love with that woman for so many years," he said. "She didn't even know it. Thanks for showing me this. It brings back wonderful memories."

"Remember what she knew you as?" Ciesynski asked. "She knows you as Johnny."

It went downhill from there.

"I didn't do it," he asserted.

"Who did it?" Ciesynski pressed.

"I have no idea."

Some eight hours had passed since McCullough was asked to take a ride downtown.

"You do realize that you are under arrest," the cop finally said, bringing out his handcuffs.

"We're done. We're done. Where's my lawyer?" McCullough said.

At 3 a.m., the cops called Clay Campbell, the top prosecutor in DeKalb County, Illinois. The Seattle cops transmitted a video copy of the interrogation.

"Clay, you've got to watch this," homicide cop Steiger told him.

"It speaks for itself."

'You need to do the right thing'

Clay Campbell huddled in his office with his two top assistants on the last night of June 2011. A computer screen flickered in the darkness as they uploaded the interrogation video.

Campbell had been elected state's attorney seven months earlier, after working 20 years on the other side of the courtroom as a criminal defense attorney. He'd been a maverick candidate, and Sycamore's legal establishment was not pleased that he had won. Folks whispered that his pursuit of the Ridulph case was political grandstanding. That a trial might be nicely timed to his campaign for re-election.

As they watched the interrogation tape, the prosecutors went back and forth. Do we have enough to charge him?

Julie Trevarthen was struck by McCullough's reaction every time the topic turned to Maria. His demeanor changed, and he grew quiet, almost reverential as he described Maria's big brown eyes.

"This isn't just a guy where things broke bad one night while he was hammered and otherwise he's a decent guy," Trevarthen said. "He is inherently evil."

Campbell agreed. He thought McCullough displayed a creepy fixation for Maria. But he knew all too well the hurdles they faced. Witnesses were literally dying on them. For every one they tracked down and found alive, three or four were dead.

Their efforts to solve the case had already met resistance. People were telling him, "There's no way you can possibly prosecute a 55-year-old murder."

But Campbell felt driven by the memory of Maria. He'd practically become a member of Chuck Ridulph's family. He'd gone through photo albums, even Maria's old homework assignments. He felt a strong connection to Maria's older brother and his loss. After all, Campbell had daughters, too. How would he react if someone snatched them in the night?

"Cold cases matter because dead children matter," he told his prosecutors.

"There's a family out there who never learned who killed their child." To him, that meant more than winning or losing any trial — or any election.

McCullough had denied everything. But his demeanor convinced the prosecutors he was guilty. He was lying, hiding something.

"You probably have enough to charge him," Trevarthen told her boss.

At 38, Trevarthen was a natural-born prosecutor who stood up fiercely for crime victims. She has green eyes that have seen too much, and views the world in terms of right and wrong, good guys and bad guys.

"You need to do the right thing for Maria," she told Campbell, "and whatever comes of it, comes of it."

He knew she was right. They would go for it, consequences be damned.

A few days later, just before the July 4 weekend, Kathy Chapman's phone rang, and all those buried childhood memories came rushing back again. It was Campbell, calling from his office in Sycamore.

"Kathy," he said, "are you sitting down? We've made an arrest."

For the first time, Kathy learned the accused killer's name. She realized he'd lived just around the corner from her and Maria.

"Johnny" was real, but he was no longer a threat.

That night, a pink rose appeared on Maria's grave in Sycamore's Elmwood Cemetery, just a few blocks from where she was snatched half a century before. A note was attached.

"We got him."