Taken: The coldest case ever solved

Written by Ann O'Neill • Video by Brandon Ancil • Photographs by Jessica Koscielniak

Chapter 3 — Bulldogs on the case

Eileen Tessier was dying, and there was one secret she would not take to her grave. She'd kept it for 36 years – much too long.

"Janet," she called out, according to her daughter's courtroom account many years later. There was urgency in her voice.

Janet Tessier rushed to her mother's hospital bed. Eileen's blue eyes were wide open. She grabbed Janet's wrist and spoke again.

Those two little girls, and the one that disappeared, John did it. John did it, and you have to tell someone.

Janet knew immediately what her mother was saying: that Janet's half brother John had kidnapped and killed Maria Ridulph. The second-grader's unsolved murder had haunted their hometown of Sycamore, Illinois, for decades.

Was this a confession, an unburdening of the soul, as Janet believed? Or could it be the ramblings of a dying cancer patient, a mind fogged by morphine?

Either way, it was a breakthrough moment in a case that cast a long shadow over Janet's childhood. The words Eileen Tessier spoke on her deathbed compelled her daughter to "tell someone" many times. It would take her nearly 15 years to find someone who listened.

Janet was just a baby when her 7-year-old neighbor vanished three weeks before Christmas in 1957. She grew up knowing there were bogeymen out there. Even in sleepy Sycamore, strangers could grab little girls off the street and make them disappear.

On Saturdays, kids from the neighborhood would walk to a matinee at the movie theater downtown. Afterward, they'd go around the corner for ice cream cones, then stop at the Sycamore police station and stare at the wanted posters. It passed for excitement in a small town.

Janet would study the sketch of "Johnny," the man suspected of snatching Maria, but nothing clicked. It was the photo of Maria that truly haunted her. "I would stand in front of the poster and stare at her face and I would close my eyes and clench my fists and pray really hard that God would find the bad man that killed her," Janet recalled half a century later on a radio show.

Over the years, she heard her older sisters recount the night of the kidnapping. They said police later knocked on their door, and they listened as their mother said something they knew was not true: that John was at home the night Maria disappeared.

The scene at their mother's deathbed confirmed these suspicions. They knew she often lied to protect John. But had she literally let him get away with murder?

Eileen Tessier died on January 23, 1994; some 300 people attended her funeral. But John was not welcome. His siblings told him to stay away.

The family's darkest secret had finally surfaced. Now the story of "Johnny" and Maria was Janet's burden to carry.

Case closed?

Janet had seen her brother's scary side.

She was 21 and trying to figure out what to do with her life when John, the big brother she'd grown up believing was a war hero, invited her to come stay with him in Tacoma, Washington, and help with his photography business. He was in his late 30s and just divorced for a second time.

They were fetching coffee on the way to a photo shoot when she made what she believed was an innocuous remark. He turned and looked at her with an expression of "utter hatred," she recalled during her March 30 interview on the Money Matters Radio Network. He suddenly seemed like a different person, and she couldn't understand what had triggered it. Seconds later, John acted like nothing had happened.

Another time when they argued, she said, he pulled out a gun and laid it on the table. He said he would kill her and tell everyone she ran away. That he would dump her body where nobody could find it.

She packed and headed home.

Now, all these years later, her mother's words tugged at her conscience and wouldn't let go.

She called the Sycamore police several times, she said, and got the bureaucratic shuffle. Other family members urged her to just let it be.

It's an old case, they told her.

Just forget about it.

She pushed it to the back of her mind for a while, but it never really went away.

One day, she called the Chicago office of the FBI on a whim. Agents referred her to the original jurisdiction, Sycamore. Again, she didn't get anywhere. In October 1997, as the 40th anniversary of the crime neared, it became clear why. A detective, Patrick Solar, had identified a suspect and declared the case closed.

Using an FBI offender database, Solar had linked the crime to a transient truck driver with a history of enticing and sexually assaulting girls in Ohio and Pennsylvania. The suspect, who also worked as a Ferris wheel operator, was dead. He'd been investigated in Pennsylvania for the 1951 murder of an 8-year-old girl but never convicted. The child had been sexually assaulted, and her body left in the bed of a pickup truck. Solar noted that the crimes were similar and concluded that the suspect physically resembled "Johnny."

The people of Sycamore had never wanted to believe that one of their own could be capable of such a terrible crime. Solar's sleuthing gave them all the proof they needed: A stranger was to blame.

Solar told CNN that he never would have suspected John Tessier. He knew the family; for years, John's stepfather painted the insignias on the sides of Sycamore police cars. Solar said Janet never spoke to him about her suspicions. Had she, he would have checked his files and seen that John Tessier was investigated and cleared by the FBI in 1957. He would have told her he needed more to go on.

The Ridulph case had occupied Solar for years. A decade earlier, when he had identified yet another suspect, Solar had gone in search of Kathy Sigman, the girl who was with Maria and saw the kidnapper. He wanted to show her a photo of the man he believed to be Maria's killer.

By then, Kathy was in her mid-30s, married and a mother. The disappearance and death of her friend had haunted her all her life. When the detective asked where he could find Kathy, her father told him enough was enough — to just "let sleeping dogs lie," Solar recalled.

Someone did give Kathy an article about Solar's 1997 investigation and his claims to have solved the Ridulph case. She never read it. She sighed, folded up the paper and put it away in a drawer. She was relieved to think that "Johnny" was dead. He could no longer hurt her.

'I'm putting my bulldogs on this'

A decade later, Janet Tessier met the author of a book about an unsolved murder. Mark Lemberger's "Crime of Magnitude" details the 1911 abduction and slaying of a 7-year-old girl.

How does a person look into an old murder case? she asked him.

Janet seemed nervous, stressed, Lemberger recalls, and her body and voice trembled as she spoke. She told him what her mother had said on her deathbed and seemed desperate to lift the weight of the secret she had held for so long.

Her mother insisted she tell someone, she said. But no one she had approached would listen. What more could she possibly do?

You have to find the right investigator, Lemberger told her. Someone who would pursue the case with "the tenacity of a bulldog."

Janet's father, Ralph, had long discouraged her from dredging up the past. But after he died, she decided to try the police one last time.

She found a tip line on the Illinois State Police website and typed this e-mail:

"Sycamore, Illinois. December 1957. A seven-year-old child named Maria Ridulph vanished. Her remains were found in another county several miles away in early spring of 1958. I still believe that John Samuel Tessier from Sycamore, IL — AKA Jack Daniel McCullough — was and is responsible for her death. He is living in the Seattle/Tacoma Washington area under the name Jack Daniel McCullough.

"I've given information to the person responsible for the cold case in Sycamore. I've done this a few times. Nothing is ever done.

"This is the last time I mention this to anyone. What information I do have makes Tessier /McCullough a viable suspect, and worth looking into. I'm not going to keep doing this over and over. It's exhausting and it dredges up painful, horrible memories."

At 1:04 p.m. on September 11, 2008, she hit "send."

The frustration in those last lines caught the eye of Tony Rapacz, a state police commander based in Elgin. He wasn't sure how seriously to take the tip. But he'd been a cop for 25 years, long enough to know that even a scrap of information can lead to something big.

His first phone conversation with Janet lasted 45 minutes. She began by telling him she was just a year old when the events occurred.

OK, here we go, Rapacz thought. Not a good sign.

But then Janet described how her mother was dying when she told her it was her brother who kidnapped and murdered Maria.

He sensed there just might be something to what she was saying.

"I can't promise you anything," he told her, "but we're going to try."

"You've got to try," Janet pleaded.

"I know," he responded. "I was afraid you were another crackpot when you called."

"Do you think I am?" she asked.

"No."

And then he said something that sent a shiver down her spine:

"I'm putting my bulldogs on this."

'Sycamore's 9/11'

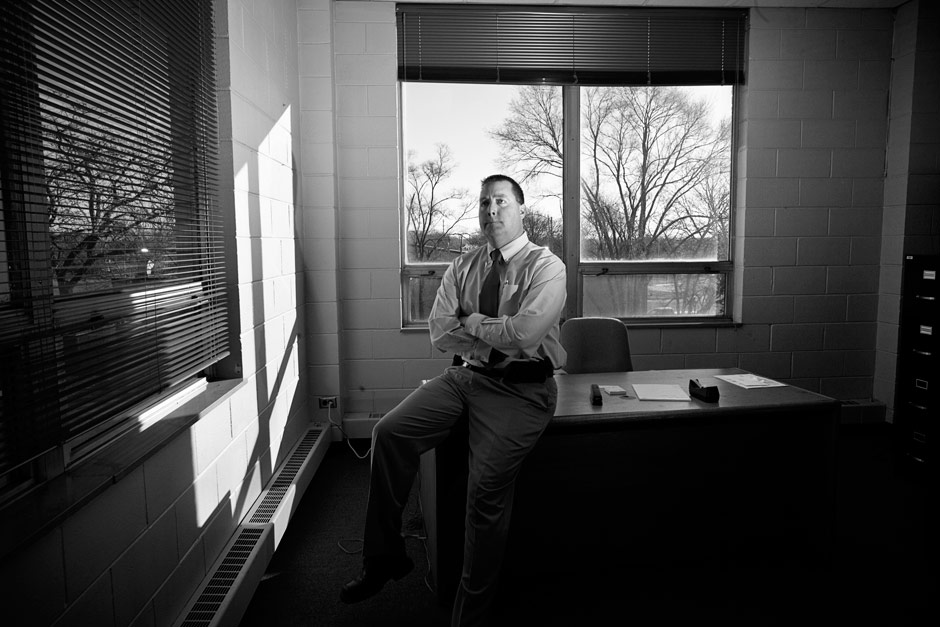

Larry Kot and Brion Hanley were the commander's bulldogs.

Kot is a mild, scholarly man of 57; he doesn't carry a badge or a gun and is not the type to shrug on SWAT gear and kick down doors. He could easily be mistaken for an accountant or a high school principal. In his off hours, he's a town alderman.

He's also a detail guy well known in Illinois State Police circles for his photographic memory and ability to find anyone or anything on the Internet. In his role as a civilian analyst for the police, he assembles the bits and pieces of a case into a seamless timeline. He connects the dots.

Kot had never heard of the Ridulph case. But a quick Google search clued him in. This unsolved case had been a big deal.

Hanley joined the case a couple of weeks after Kot. A special agent with the investigations division, the 41-year-old Hanley favors college football jerseys and turned-around ball caps when he works undercover, which is most of the time. He usually has a wad of chewing tobacco parked in his cheek. His open, friendly face seems to get people talking.

The early stages of an investigation are the most tedious: tracking people down and getting them to open up. Hanley's legwork began with Janet Tessier and her siblings, who were scattered from Illinois to Wisconsin to Kentucky. None had good things to say about John, especially Jeanne.

Hanley was surprised by how open she was, how articulate. Maybe it had something to do with her work: She taught college classes in communications, counseled parents of dying children and was active in the community of sexual abuse survivors. Whatever the reason, Jeanne spilled the details of what she said was another family secret.

John sexually molested her while they were growing up, she told Hanley, and forced her to stand watch while he molested other neighborhood girls in the bushes and in a stairwell at West Elementary near their home. She said he raped her and offered her to his friends while he was home on a military leave. At the time, she was 14.

(Janet and Jeanne Tessier declined to speak with CNN, which does not usually identify victims of sexual assault. But Jeanne Tessier has openly discussed her allegations against her brother in Sycamore's local newspaper and in a network television interview. Her account here is drawn from court transcripts and other public records.)

Hanley knew Jeanne Tessier was an accomplished woman who would make a credible witness. He also found that many of the people he wanted to talk to were alive, healthy and willing. It helped that Maria's murder had been such a transformative event. People remembered it.

Hanley came to think of the case as "Sycamore's 9/11."

Many of John Tessier's old high school friends still lived within a few miles of the town. Some told Hanley that Tessier was supposed to pick them up at a hobby shop the night Maria vanished but stood them up. Tessier's sisters said he wasn't at home that night as their mother reported to police — or the next morning. His oldest sister, Katheran, said she didn't see his car that day, either.

Years earlier, Tessier had told the FBI that he and a high school classmate helped search for Maria the night she was kidnapped. He added a curious detail: He said they'd found some dirty magazines and turned them over to police.

Hanley poked holes in that story, too. He found the classmate, who told him he never saw Tessier. And, the witness added, had he found any dirty magazines as a teenager, he would have kept them. Sycamore police had no record of anyone turning in magazines, smutty or otherwise.

And then there were the piggyback rides. Maria's kidnapper gave her a piggyback ride to win her trust. Hanley unearthed the story of another piggyback ride three or four years earlier. Only in this case the little girl had lived to tell about it.

Pamela Long said she was about Maria's age when an older boy she knew from the neighborhood gave her the ride. There was no doubt who he was: Long knew John Tessier by name. Neighborhood kids thought he was weird and called him "Commando."

His grandparents lived directly behind her family's home in the nicest part of town.

She recalled how he walked up and down the street wearing camouflage pants and waving a wooden sword. She wasn't supposed to play with him, but she couldn't resist a piggyback ride.

It so upset her father that he pulled her off the teen's back, sternly warned him to stay away and reported the incident to Sycamore police. After Maria was taken, FBI agents showed up at school to question Long about that piggyback ride. Whatever she told them, it wasn't enough to keep "Commando" on the list of suspects.

Long's father announced at the supper table: He'd better have a damn good alibi.

A new timeline

The timeline of events on December 3, 1957 – and John Tessier's alibi – were central issues in the investigation. Kot believed misinformation and faulty conclusions had entered the case during its early hours. He began building a detailed timeline to test those old assumptions.

It took months to gather all the documents scattered among the Sycamore police, Illinois State Police and the FBI archives. But Kot's paper chase brought in thousands of pages, which he studied, tabbed and organized in binders. His timeline grew to cover three walls of his office. And as he looked closer, he saw that there were only two sources for Tessier's alibi: Tessier himself and his parents.

Tessier said he was in Chicago the morning of Tuesday, December 3, taking a physical to gain entry into the U.S. Air Force. Kot was able to verify that. But he learned that Tessier left the recruiting station by noon that day. He later was seen in Rockford, nearly 90 miles from Chicago, at about 7:15 p.m. But there was nothing to verify his whereabouts between noon and 7:15 p.m., which means he easily could have returned to Sycamore before showing up in Rockford.

Initial reports set Maria's disappearance at about 7 p.m. But reading the old files, Kot realized that information may have been injected into the case by the kidnapper himself. When Kathy ran home to fetch her mittens, she asked "Johnny" what time it was, and he told her it was 7 p.m.

Kot dug up an Illinois State Police report dated July 27, 1958 – three months after Maria's body was found. "We feel certain facts may have been overlooked," it began, concluding that Maria had been taken earlier than initially reported, and that her abductor had probably escaped by running up the alley and jumping into a car parked on a back street.

And so, Kot homed in on facts that had been ignored earlier because they didn't fit the original 7 p.m. timeline. Phone records and other details fleshed out after the first chaotic days of the investigation had prompted the girls' mothers to adjust what they believed to be the timing of events. At first, Maria's mother said the girls went outside at 6:30 and that Maria came back in for her doll at 6:40. Later, she said Maria could have gone out as early as 10 minutes to 6.

Kathy's mother set the precise time at 6:02 p.m., although the reason for her precision has been lost to time. Maria's mother pulled out of her driveway at 6:05 p.m., taking daughter Kay to a music lesson. Frances Ridulph recalled waving to the girls, who were playing in the street in front of the house.

Kot examined closely the accounts of the most neutral, credible witnesses at the time: A heating oil deliveryman and a city bus driver.

Tom Braddy knew Kathy Sigman and her family, and he recalled that she waved at him as he stopped to deliver oil at the big white house on the corner of Archie Place and Center Cross Street, where the girls were playing. He estimated he got there about 6 p.m. and spent 15 to 20 minutes delivering his load. He noticed the time on a clock at a service station as he headed back to his office: 6:20. He did not see the girls on the corner as he left.

A city bus passed by that corner at 6:30 p.m. The driver said he saw no one there.

Kot concluded that Maria was taken no later than 6:20 p.m. If Tessier parked his car in the back alley where Maria's doll was found, he could have headed straight to Rockford with Maria in his car. It was a 40-mile trip, give or take a few miles, but there would have been little traffic on the back roads in 1957, and he easily could have made it to Rockford in less than an hour.

A collect phone call placed in Rockford to the Tessier home – a key piece of John's alibi — also fit into the new timeline.

Phone records showed the collect call was placed at 6:57 p.m. but they didn't pinpoint where in Rockford the call was made. Tessier could have called home from a pay phone on the outskirts of town.

Maybe, Kot thought, Tessier's alibi wasn't so ironclad after all. Maybe the phone call from Rockford wasn't Tessier asking his stepfather to pick him up at the recruiting station there, as he'd maintained. Maybe the call was made by a nervous Tessier wanting to see if anyone was looking for Maria yet.

As they drilled down deeper into the case, Kot and Hanley also found a reason why Sycamore police might not have taken a closer look at Tessier as a suspect. It was a small town and everybody knew everybody else. His stepfather, Ralph, was friendly with the police chief, William Hindenburg. John himself had volunteered to the Air Force recruiter that he'd never be a suspect in the girl's disappearance because his girlfriend's father worked for the DeKalb County Sheriff's Office.

The girlfriend, then known as Jan Edwards, was part of his story, too. He said they met for a date at about 9:20 that night, after his stepfather picked him up in Rockford and brought him home. Kot and Hanley tracked her to Florida, where she and her husband had retired. She agreed to talk about her old high school boyfriend, but only if she could have her lawyer with her. She was a reluctant witness, perhaps, but she gave Hanley and Kot one of their biggest breaks.

She told the cops she never saw Tessier on the night of December 3. Her parents were so upset about the abduction of Maria, so afraid a crazed kidnapper was on the loose, they wouldn't let her out of the house.

Hanley asked whether Edwards had a good picture of John from 1957. He hoped to show a photo lineup to Maria's friend, Kathy, who had seen and talked to "Johnny," the kidnapper.

Because Tessier was expelled from school, there was no 1957 yearbook photo of him that accurately showed what he looked like then.

What are the chances someone would save a photo from a high school dance half a century ago? Jan Edwards told the cops she'd take a look. She called a few days later. Yes, she had found a picture of John. It was taken at a formal in June 1957. She'd be happy to mail it.

When the photo arrived at the state police offices in Elgin, outside Chicago, Hanley was pleased he had something he could work with. On the back was a bonus: It was signed, "Love, Johnny."

Another break came when he pulled the photo from its cardboard frame. A small, yellowed square of paper fluttered out. It appeared to be a government-issued train ticket. Tessier was supposed to use it to travel to Chicago for his induction physical on December 2. The train would leave from Rockford; there was no passenger train from Sycamore.

It was a one-way ticket, and it didn't appear to have been punched. Kot reasoned that Tessier never took the train to Chicago on December 2. He must have found another way to get into the city, most likely his own car. And if he had his own car in Chicago, he could have driven back to Sycamore on December 3, during the noon to 7:15 p.m. window in which his whereabouts could not be verified.

A high school friend later told Hanley that he remembered seeing Tessier's car cruising through Sycamore at about 2:30 p.m. on December 3. He didn't see who was behind the wheel, but he knew Tessier never let anyone else drive his baby.

Cops are cautious by nature. But even if Hanley and Kot weren't dancing around the room exchanging high fives, this was huge. They'd poked a big hole in Tessier's alibi. If he'd lied about how he got around, what else was he lying about?

Kot sent the ticket to the Illinois Central Railroad Historical Society, and the cops got the word on June 2, 2010: The ticket was authentic, and it had not been punched.

They now felt certain they could solve this cold case.