Taken: The coldest case ever solved

Written by Ann O'Neill • Video by Brandon Ancil • Photographs by Jessica Koscielniak and Brandon Ancil

Chapter 2 — Where's 'Johnny'? A trail of women wronged

John Tessier left his parents' house in Sycamore, Illinois, for good on December 11, 1957 — eight days after Maria Ridulph disappeared.

He says he didn't often think about what happened to the little girl who lived around the corner. He remembers talking with her just once. But he never forgot her.

More than half a century later, police and prosecutors would find it disturbing how Tessier's voice softened every time he spoke of her beauty and those big brown eyes. He'd smile and his own pale blue eyes would get an odd, faraway look as he told people she was "lovely, lovely, lovely" and "like a little Barbie doll."

John Tessier is Jack McCullough now. He is 73 years old and recently met with CNN at a state prison in southern Illinois. He told the story of how he protected Maria that one time they met.

He was about 13, he said, and she was tiny, about 3, when he found her wandering alone at the corner of busy Center Cross Street, the very spot from which she would disappear four years later. He said he told her to go home and stood in the middle of the street and watched for cars as she trotted up her driveway and got safely inside.

"You gotta understand," he said, "we boys protected all of the children in the neighborhood. When Maria was taken, it was an affront. Our lives would never be the same after that. Our neighborhood wasn't the same anymore."

Sycamore was changed forever by the Maria Ridulph case – one of the few indisputable facts in the oldest cold case to go to trial in the United States. The case was controversial from the start: It was built on circumstantial evidence, the time of the kidnapping is in dispute and an alibi the defense calls "ironclad" was never presented in court.

Five decades after Maria was kidnapped and killed, cops would call the crime "Sycamore's 9/11." It shook the place that hard. But while the town of 7,000 struggled with its loss of innocence, John Tessier spent most of his life elsewhere.

He joined the Air Force, and then the Army. He attended officer training school and served in battle in Vietnam as a lieutenant, twice winning the Bronze Star. He'd always felt destined to be a soldier, he told CNN. After all, John's grandfather served in Britain, and his mother was in the Royal Air Force, one of the first female searchlight operators during World War II.

In one of his earliest memories, he is being carried up a flight of dark, narrow stairs in London on the back of a soldier. He believes it was his father, killed in the war, giving him a piggyback ride.

With both parents in the military, he spent his youth in the English countryside, in the care of an elderly couple and isolated from other children as war ravaged London.

When he was about 7 and his mother brought him to Sycamore, Tessier seemed an odd duck. He didn't know how to act around other children. He walked the streets wearing camouflage pants and waving a wooden sword — "Commando," the neighborhood kids called him. He loved the popular Civil War song "When Johnny Comes Marching Home." He identified with it.

"My name was Johnny and that's what I wanted to do. I wanted to come home the hero," he told CNN. "My DNA is protector."

That statement reveals an alarming disconnect between how he views himself and how others who crossed his path describe him.

Some say he was a screw-up. To others, he was a masterful manipulator. To some women, especially the younger ones, he was a lecher and worse, a menacing sexual predator. Later in life, he did settle down with a woman who, with her daughter, came to view him as he always viewed himself — as a mentor and protector.

The FBI showed an interest in John Tessier during the early days of the Maria Ridulph investigation in Sycamore. But 50 years would pass before authorities would look for him again. The four-year investigation took agents with the Illinois State Police from Sycamore to Seattle.

When it was over, Johnny came shuffling home in shackles.

The alibi

Today, police would call him a "person of interest," someone they want to question. But in 1957, long before televised murder trials and the threat of litigation from people mistakenly tied to crimes, 18-year-old John Tessier was a suspect, pure and simple. Then again, so were 100 other people.

A woman who would not give her name called the sheriff's office with a tip on December 6, three days after the kidnapping. She told deputies to check out a boy named "Treschner," who lived not far from Maria and fit the description of the kidnapper who called himself "Johnny." The FBI found no one named Treschner but zeroed in on John Tessier.

The story of the early investigation is contained in thousands of pages of FBI reports, but most of them remain sealed because of an ongoing investigation the Justice Department would not discuss. CNN obtained about 15 pages from the public court file in Sycamore, and another 200 pages from the National Archives through a public records request. They spell out Tessier's alibi.

He said then, and he says now, that he was in Rockford, Illinois, some 40 miles northwest of Sycamore, when Maria was kidnapped and that he called home for a ride. His parents backed up his story, and it was supported by a single, indisputable fact: Somebody placed a collect call from Rockford to the Tessier home at 6:57 p.m. on December 3, 1957. The caller gave his name as "John Tassier," the operator noted.

But almost from the beginning, the timing of Maria's disappearance was in dispute.

If she was taken around 7, then Tessier seemed to have an ironclad alibi. But if she was grabbed closer to 6:15, then his alibi didn't cover him. He could have driven from Sycamore to Rockford by 7 p.m. before dumping her body.

Nobody disputes that John traveled December 2 to Chicago to take a physical examination at the military recruiting station on Van Buren Street.

A chest X-ray found a spot, and he failed. He spent the night at a YMCA and returned the next morning for another physical, which he again failed because of the spot, a scar from a childhood bout of tuberculosis.

Tessier said he walked around Chicago the afternoon of December 3, stopping in at a couple of burlesque shows, and then took the 5:15 p.m. train to Rockford, about a 90-minute trip, to drop off paperwork at the recruiting station there.

Recruiters verify that he showed up at their office between 7:15 and 7:30 that evening, after they had closed. He talked with at least two recruiters about getting a note from his doctor to address the spot on his lung. One recruiter told the FBI he thought the nervous young man was a "narcotic," a drug addict. The other remembered him as "a lost sheep."

A third recruiter, Staff Sgt. Jon Oswald, met with Tessier the morning of December 4 at the Rockford office. The recruit had a fresh cut on his lip and made small talk, saying it was a good thing that he was not in Sycamore the previous night because of "the disappearance of the girl," Oswald recalled for the FBI.

Tessier also told the recruiter he'd never be considered a suspect because his girlfriend's father was a deputy sheriff. And then he showed Oswald his "little black book." It contained the names and addresses of girls in Sycamore, as well as their bust and hip measurements.

The FBI questioned Tessier on December 8, and two days later gave him a lie-detector test. Asked whether he ever had sex with children, Tessier admitted being "involved in some sex play" with a younger girl but said it happened years earlier. He said he'd outgrown it and had no relationship with Maria, although he acknowledged he knew her from the neighborhood.

Those details and his peculiar behavior with the recruiters didn't seem to raise suspicions at the time. Nor did his mother's contradictory stories: She'd told local police her son John was home all night December 3, and FBI agents that he was in Rockford that evening.

The more precise question was: Where was John Tessier between noon and 7 p.m. on December 3? Records placed him at the Chicago recruiting station that morning, but his whereabouts remained unaccounted for until he turned up at the Rockford recruiting station at about 7:15.

The FBI had only his uncorroborated version of what he did that afternoon.

Did he pass the time in Chicago and take a 5:15 train to Rockford, as he said? Or did he somehow make his way back to Sycamore?

An acquaintance recalled decades later that he spotted Tessier's car in Sycamore that afternoon, before Maria vanished. The Pontiac was hard to miss — it had flames painted on the sides — but the man didn't see who was behind the wheel.

'No evidence of guilty knowledge'

Tessier remembers that his mother was crying as he went off to talk to the FBI on December 8. He says he comforted her, telling her everything was going to be all right.

He told the FBI that after he made the collect call from Rockford he killed time at a restaurant, waiting for his stepfather to pick him up. He remembered having to run back to the recruiting office to pick up a shaving kit he'd left behind.

Ralph and Eileen Tessier told the FBI that Ralph drove to Rockford to fetch John at about 8. Years later, John's half sister, Katheran, would come forward to dispute the timeline her parents gave, saying her father was in DeKalb, the town next to Sycamore, taking her to a 4-H social that lasted from 5 to 8 p.m. She recalled coming home to find the street lined with police cars, and soon after that, her father was opening up the hardware store to supply flashlights for the search.

But back in 1957, the Tessiers' story seemed to check out. John passed the lie detector test; the FBI's expert concluded that a teenager wouldn't have been able to conceal his involvement in the crime.

"The recorded reactions on the polygraph did not reflect evidence of guilty knowledge or implication by Tessier in this matter," the polygraph examiner concluded. An FBI agent closed out his report on December 10 by noting: "No further investigation is being conducted regarding the above suspect."

John Tessier's name was scratched off the list. He left Sycamore the next day.

'Consistent in screwing up'

It is not unusual for people who leave the military to gravitate toward police work. The macho culture, the command structure and the discipline seem a natural fit. But if John Tessier rose through the ranks in the Army, he was a washout as a cop.

Tessier was in his mid-30s, a captain fresh out of the Army and living in Washington state, when he graduated in June 1974 from the King County law enforcement academy and found a job in the small town of Lacey, near Olympia. The job had its perks. It allowed him to portray himself as rescuer and hero – particularly to women.

A marriage that produced a son and a daughter had fizzled. As a Lacey cop, he found his second wife, Laura.

She was a student at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma and came from money. Her father was looking for off-duty cops to moonlight as bodyguards. Newly single, Tessier jumped at the chance. It wasn't long before a romance blossomed.

They were married for three years but broke up, he said, "because I cheated on her."

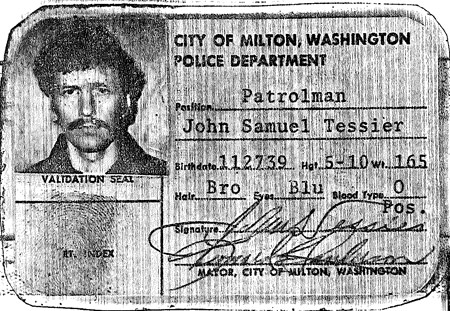

By 1979, he was working for a much larger department in Milton, near Tacoma, where he continued to indulge his interest in the ladies.

Police Chief Harold Burton viewed Tessier as inept and insubordinate and fired him for tipping off a drug suspect. Tessier fought the case, prompting the chief to document his complaints in a letter to the city's lawyers.

The police station was constantly receiving calls from Tessier's bill collectors, Burton wrote, and he loudly told dirty jokes in restaurants during breaks.

And then there were the women.

"Five incidents have been brought to my attention involving local women, three of which were contacts made as a result of police involvement," the chief wrote. They included a woman Tessier arrested for drunken driving; she later moved into his apartment. Another woman called police about someone slipping obscene photographs through a window; Officer Tessier responded, and before long they had struck up a relationship. The chief said he personally had seen Tessier's car parked all night outside her apartment.

Tessier got involved with a third woman who worked for the city and was going through a divorce; the drama spilled over into loud barroom arguments with the woman's ex, the chief wrote. There also was the woman he brought to a town party: She had been arrested for prostitution.

And, Tessier took topless photos of a 17-year-old waitress "in a Playboy type pose."

"Tessier is not very well liked by his coworkers and several complaints have been received about his conduct from other police departments," the chief wrote. He added that Tessier's infractions weren't serious. "But," the chief said, "he is consistent in screwing up."

Tessier was reinstated, but it wouldn't last long. In just weeks, a teenage runaway would end his police career.

'They made me feel like dirt'

Michelle Weinman says she fled the wrath of her father and ran into the hands of a man who would abuse her in his own way.

She was 15. He was a cop.

CNN usually does not name the victims of sexual assaults, especially underage victims. But Weinman, now 46, agreed to tell her story on the record and to be photographed. She says stepping out from behind the stigma has helped her heal.

She'd lied about skipping detention at her high school on the outskirts of Tacoma, Washington, and knew her father would punish her. So she ran away. She was joined by a friend who knew a Milton policeman who said they could stay with him. The girls slept on a hide-a-bed in the living room of John Tessier.

He was in his 40s by then, but he wasn't playing the father figure. "He was as old as my own father, but he would try to be the cool guy," Weinman told CNN. He took her to the movies, out to dinner, to the mall. He taught her to drive in his squad car at a park overlooking the city. He let her work the lights and siren, and that was exciting. He made sure she stayed in school.

He bought her the first record album she ever owned, Joan Jett's "I Love Rock 'n' Roll." But first, he made her promise she'd be good.

He taught her how to dress and apply makeup. She thought that part of their deal was strange, but he was a police officer, so she trusted him.

"I was raised to fear God, trust police officers and respect teachers," she said.

Then came the massages: She'd lie on the floor while he moved his hands over her back.

He told her she could work in a massage parlor when she got older. He pulled down her pants and rubbed her buttocks. It was creepy and made her uncomfortable, but she never said anything to anyone.

Weinman felt grateful for a place to live.

During the weeks the girls stayed at his apartment, Tessier made a habit of kissing them goodnight. One evening, he gave Weinman's friend "a boyfriend kiss."

"And she said, 'Does he do that to you?' I said, 'Gross, no.'"

Weinman assumed if any funny stuff happened, he'd focus on the other girl, who was more developed, more mature. But then one night, Weinman says, he came for her.

She was asleep on the sofa bed. He whispered in her ear, waking her. Before she could figure out what was going on, she said, he was performing oral sex on her.

"I couldn't stop it. I think I just lay on the couch and froze. I couldn't scream. I was so scared. I was ashamed."

She told her girlfriend, and a counselor pulled Weinman out of class the next day. Police questioned her, but they didn't seem to believe her.

"They were really, really mean to me," she recalled. "They scared me so bad. I didn't know how to tell them what had happened. So they started yelling at me. This one particular guy started yelling at me and telling me I was nothing but a tramp, telling me he was going to make it look like I wanted it, that I begged for it. That they were going to make my life hell, that they were going to drag me through the mud."

There was no medical exam, no counseling, not even a female police officer to question her, she said. "I was turning in a police officer for violating me in the most vulgar way. They made me feel like dirt. They made me feel like I didn't deserve to be happy."

The investigators, all men, worked for a larger department from a neighboring town, Weinman said. But they made no secret that they were not happy she was accusing a cop.

John Tessier was charged with statutory rape but pleaded guilty to a lesser charge: communication with a minor for immoral purposes. He denied then and denies now that he sexually assaulted Weinman, and says he took the deal because he couldn't afford a lawyer. He was placed on probation for a year and quietly resigned from the Milton Police Department on March 10, 1982.

Weinman said she blocked the experience from her mind for more than 30 years — until an agent with the Illinois State Police walked into the bar where she works and asked about John Tessier.

'He let me go'

Tessier was a struggling photographer in the early 1980s when one of his models introduced him to Denise Trexler. She was getting out of an abusive relationship and needed a protector. Tessier liked that she was well-educated and held a steady job as an engineer designing electrical systems for Peterbilt trucks.

She owned a nice house, and she had class.

Tessier quickly installed himself as a bodyguard of sorts. He moved into her house in Tacoma and within three months they were married.

It's a time in her life she'd rather forget; it's a time he won't talk about, except to say he won't badmouth Trexler. She spoke briefly over the phone with CNN. She is retired now and happily married to someone else.

She recalled how Tessier became controlling and emotionally abusive soon after they exchanged vows. Her knight in shining armor was manipulative and "on the emotional level of a 4-year-old."

"You know the type," she said. "They reinvent themselves to make themselves look good or convince you who they are. They find someone with some money and their status looks good. And they move on in. They're self-centered, egotistical asses."

As he had with Michelle Weinman, Tessier taught Trexler how to dress and apply makeup the way he liked. He told her he kept her around so he would seem "respectable."

To maintain control, he constantly ran her down.

"You're never good enough, pretty enough," she said. "You always have to look your best. Your makeup has to be perfect. You're controlled, you can't get out. If you want to get out, you're going to die."

She learned not to believe a word he said.

He did not talk about his family much, but she did meet his parents when they visited Seattle. She found them to be "wonderful." She had the impression that her husband was slightly afraid of his mother. She seemed to be the one woman he respected: "You didn't mess with her. She said something, he did it."

She never met any of his half sisters; Tessier told her he didn't like them.

"We never talked about the past," she said. "Whatever he told me, it probably wouldn't have been the truth."

He never mistreated her sexually, she said. In fact, their relationship was mostly platonic.

They stayed together on and off from 1983 until 1989, when he told her he'd met someone else. She didn't put up a fight.

"He let me go," she said. "I feel really lucky."

Asked whether she ever saw any signs of sexual impropriety, Trexler recalled two incidents she found particularly disturbing. They involved his daughter from his first marriage, who stayed with them for a short while when she was about 12.

One morning, she found Tessier and his daughter in the kitchen. He was holding a banana in a particular way and making sexually suggestive comments.

Later, while looking for something in a desk, she felt the drawer catch. She ran her hand along the bottom.

Taped to the underside was a recent picture of Tessier's daughter. She was nude.