War & Fashion

Carnage: Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria. Catwalk: Armani, Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent.

War is ugly. Fashion is beautiful. War projects the worst of humanity. Fashion displays sartorial splendor in its highest. War is fraught with danger, even for journalists and especially for photographers who must get up close to their subjects to frame an image. Fashion is far less perilous, though photographers must also get intimate with their subjects on and around the runways. There are photographers who shoot both: battlefields and runways, guns and glamour. At first, photographing war and fashion appear as incongruous acts that are difficult to reconcile.

Until, perhaps, you take a deeper look.

Gaza, 2000.

Gaza, 2000. Paris, 2006.

Paris, 2006.I laid out photographer Christopher Anderson's images of war and fashion before him. He was on a lunch break from a New York Magazine cover shoot in a Manhattan studio.

"Amazing," he said.

He'd never seen his own photographs juxtaposed like that. War belongs in one intellectual compartment; fashion in another. The two don't usually mix in project portfolios -- or in the mind.

He called over the magazine's photo director, Jody Quon, for a look. She, too, was astonished by the common threads.

Anderson captured a Palestinian youth in Gaza during the second intifada and a Giorgio Armani show in Paris. Both images are blurred, the figures airy, almost diaphanous in the light.

"It's about the optics," Anderson said.

In the summer of 2006, Anderson shot rescuers attempting to remove bodies from the rubble of a Beirut apartment building hit by Israeli jets. "Lebanon horrified me," he said.

Two years later, he clicked his camera behind the scenes at a Proenza Schouler show in New York. The composition feels eerily similar. Both images show a cacophony of chaos.

Beirut, Lebanon, 2006.

Beirut, Lebanon, 2006. New York, 2008.

New York, 2008.Then there is a photograph of 3rd Infantry Division soldiers clearing a building during the battle for Baghdad after U.S. forces entered the Iraqi capital in 2003. And a shot showing models at a L'Wren Scott show in 2008. The movement in the Iraq photo mirrors that of the models in their high heels.

"I see scared little girls who have come from all over the world, all dressed up to be something they're not," Anderson said. Just like the young men in the U.S. Army who got dressed up to fight, terrified, at times, of a still-invisible enemy.

Iraq, 2003.

Iraq, 2003. New York, 2008.

New York, 2008."People are people," Anderson said. "I see the human experience in these photos. When I'm looking to make a picture, I'm peeling back layers to get that emotional quality."

As in the photo of an Iraqi army sergeant surrendering to the Americans in Najaf.

"I don't see war," Anderson said. "I see a man who is frightened."

The idea to juxtapose war and fashion evolved after CNN's Director of Photography Simon Barnett came across a war photograph that reminded him of a fashion shot he'd seen. (See Barnett's selection of images on CNN's photo blog.)

"I got to thinking about a number of established combat photographers who have in recent years been turning their cameras toward fashion," Barnett said. "I wondered what we would find if we went deeper into their work."

Barnett did just that; he asked Magnum Photos to send him a collection of images made by four photographers -- each of whom has won major photojournalism awards.

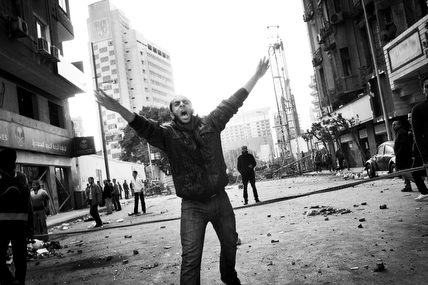

Cairo, 2011.

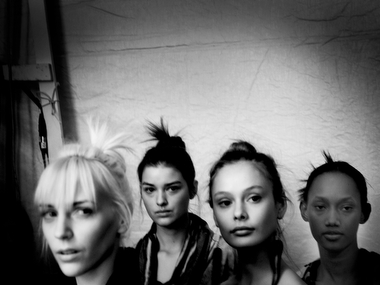

Cairo, 2011. New York, 2005.

New York, 2005.When they arrived in Atlanta, Barnett plastered the photographs all over CNN's media lab, and began moving them around.

"We saw that many photos taken by the same photographer seemingly started pairing themselves together." Barnett said. "In a very immediate and simplistic way I found this stimulating to look at, but wondered whether this meant anything."

He was intrigued by the prospect of presenting the photographers with an edgy new body of work they'd created with no conscious awareness of having done so.

Anderson and Jerome Sessini were both surprised at first but the more they talked about their work, the more it became apparent how the pairings made sense. Paolo Pellegrin and Alex Majoli, the two other photographers whose work is showcased here, were shooting a project in a war zone and could not be reached for comment.

To others, the idea of this odd juxtaposition seemed unfair. Disturbing, even.

Kabul, Afghanistan, 2004.

Kabul, Afghanistan, 2004. Paris, 2008.

Paris, 2008."Appalling," said Sonya Fry, executive director of the Overseas Press Club, which bestows the prestigious Robert Capa Gold Medal for courage and enterprise in photography.

She perceived war as serious; fashion, not.

Still, she found it interesting to compare the dynamics of the photos.

That someone had put them together fascinated Anne Tucker, curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: "It's kind of ballsy," she said.

Look at the photographs, she said. Take away the first three things you see. Perhaps the number of people. Or gender sameness. Or chaos.

Then you begin to see other realms -- of coded clothing, body posture, the relationships of people to their environment.

"Its total unexpectedness is its value. It ain't ho-hum," Tucker said.

"My experience is that combat photographers are some of the smartest people I have met. They're not just interested in conflict photography. They are image connoisseurs. It doesn't surprise me that one would inform the other."

Iraq, 2003.

Iraq, 2003. Paris, 2008.

Paris, 2008.Provocative. That's how Stefano Tonchi saw it. The mastermind behind The New York Times style magazine, T, and now the executive editor of W magazine, has worked with combat photojournalists in many fashion shoots.

"Not to say that fashion is not war," he joked. "But what is compelling about the images is the technique."

In both situations, the photographers must move fast, quick to make decisions about light and composition. They are used to catching a moment, capturing something people believe in.

"I think there are more believers in fashion," Tonchi observed, "than there are in human rights."

Author and documentarian Sebastian Junger admitted he knew nothing about fashion. But when he saw the war and fashion photos, he felt that perhaps the fashion world was a bit of a battlefield.

"It makes the world of fashion seem kind of brutal and filled with conflict," said Junger, whose collaboration with the late combat photographer Tim Hetherington in Afghanistan's Korengal Valley resulted in the gritty film "Restrepo."

Kosovo, 1999.

Kosovo, 1999. Paris, 2009.

Paris, 2009.The fashion world for Junger is all about performance. The emotions are exaggerated, even fake. The gestures, for the most part, posed.

"It's funny, in my eye. They all look like they're trying very hard to stand out, striking very aggressive, confident poses.

Not different, perhaps, than a rebel fighter posturing in front of a camera, trying to appear invincible.

That's evident in Sessini's portrait of a fighter in Libya along the road to Ajdabiya in 2011.

War, too, said Junger, can be about performance. Only the anguish is real.

Ajdabiya, Libya, 2011.

Ajdabiya, Libya, 2011. Milan, Italy, 2012.

Milan, Italy, 2012."It's not how a photographer looks at the world that is important. It's their intimate relationship with it." The words of French photographer Antoine d'Agata synthesize the work of Sessini.

"I would say shooting is conditioned by the attitude on the ground, the emotional connection with the subject. That is, my personal relationship," Sessini said.

"When this relationship is strong, my eyes and my perception take precedence over the subject, whatever it is."

The difficulty for photojournalists lies in balancing truth with emotion, information with appearance. In the 2004 Falluja offensive, Sessini photographed two Marines who were clearing houses. They are shown sitting back to back on a metal bed in a house clearly ravaged by war.

"I felt their fear. Very young and very scared. They were lost in this space, wondering what they were doing there," Sessini said.

"That's what I tried to transmit -- the psychology of the soldiers. Anxiety, fear. No sense of purpose."

In another photo that Sessini shot just last September at an Armani show, two models appear backstage, back to back, wearing the same dress, their uniform of sorts. As with the case of the Marines, you cannot see their faces but Sessini captured the essence of their emotions with their pose. Lost in the middle of a big show.

Falluja, Iraq, 2004.

Falluja, Iraq, 2004. Milan, Italy, 2012.

Milan, Italy, 2012."Showing expression most of the time, it's too easy," Sessini said. "A smile -- it's the first thing that you can see. If you search more, you can find something in the body or the posture."

Junger saw the same mechanics in those two photos but took away two completely different stories. The two women didn't seem connected.

"In fashion, there's some kind of implicit competition of who is the prettiest. In combat, it's the exact opposite. Those guys are completely connected."

It made sense to Junger that photographers focus on the same physical statements they make about individuals in fashion as they do in war. But the human form has limited focus points, the face being the most obvious one.

Pellegrin used the face, gesture and posture to get across two very different situations, said Tucker of Houston's fine arts museum.

There is a man with his arms outstretched in Tahrir Square and a model with her left arm in the air at New York's Fashion Week. The two images look similar. One emits rage, the other grace.

Cairo, 2011.

Cairo, 2011. New York, 2004.

New York, 2004.The anger in the faces of Egyptians protesting the rule of Hosni Mubarak in Cairo's Tahrir Square is evident in Paolo Pellegrin's 2011 photo. His shot of four models at Fashion Week in New York in 2005 is composed and framed in very much the same vein. Only this time, audiences come away with a look of speculation.

Another Pellegrin photo shows a man with his face covered, running during the anti-Mubarak protests. Next to it is a Paul Smith model running through brush in a corseted skirt.

Cairo, 2011.

Cairo, 2011. Paris, 2010.

Paris, 2010.There's no mistaking the circumstances in which each subject is running. The model is wearing high heels and holding up a black bag. Her jaunt lacks desperation. The man, perhaps, is running for his life.

War and fashion. Opposite worlds?

Yes, of course.

A photographer is not likely to be injured or killed at backstage Balenciaga. But take away the danger element and to Anderson, much of it feels the same.

To get through the logistics, to be able to position yourself just right is as difficult at Armani as it is in Afghanistan.

"You have to anticipate where you need to be so that when things unfold you're reacting to what's in front of you," Anderson said.

Both situations are uncontrolled. If you click too late, you've missed the drama of the moment.

Anderson sees the same sensibility in all his photographs. The same person behind every frame.

He no longer shoots war. At a certain point, he believes, he was playing with statistics.

"From a creative standpoint, I don't know what else to say about war."

But the thing is, there is beauty in war. Powerful beauty.

To understand it, you have to first understand war's ugliness.

"The volume is turned up in war," Anderson said. "If it's beautiful, it's more beautiful. The ugly is uglier."

In war, you look for beauty of the human spirit. In a single gesture. Or act.

Cairo, 2011.

Cairo, 2011. New York, 2009.

New York, 2009.For many combat photographers, fashion is the tougher subject in that it is less familiar. Pellegrin, in a 2010 interview with Reuters, said this about fashion: "It's a world I do not frequent or know well. But I did not want to dismiss it as superficial. There is a lot of talent and creativity in fashion. I came with respect and wanting to discover a world I knew not so much about."

Strangely, shooting war is sometimes less complicated, from a purely artistic standpoint. There is so much that is happening in front of you, Sessini said. It's easier to tell an extraordinary tale than craft one from the ordinary.

"For me, war photography is easier," he said. "The thing happens in front of you. You just have to frame and shoot. It's very easy to get a strong picture. At Fashion Week, it's much more difficult. You have to work, you have to find something different and find your own vision."

Shooting fashion was a challenge for Sessini. "I can feel stressed in the same way in Falluja that I feel in Milan."

Sessini found my questions interesting. No one had asked them before. He, too, had never studied his photos of war and fashion next to one another.

When you have a vision of the world, it comes through in your work, he supposed. That is true whether in war or fashion.

West Bank, 2006.

West Bank, 2006. Paris, 2008.

Paris, 2008.