Palo Alto, California (CNN) -- Long before he became a scientist investigating the building blocks of life, Rhiju Das had another goal.

He wanted to code a version of the 1987 shoot-em-up arcade game Contra for his Apple IIe computer.

"I learned some of the language and stuff like that," he said of what would ultimately be a failed effort. "Nothing came of it -- except that it demystified the whole thing for me."

Now, as an assistant professor of biochemistry at Stanford University, he's married that childhood streak of gamer curiosity with his work investigating RNA, the tiny molecules essential to life and central in the hunt for cures to diseases like cancer and AIDS.

He's the co-creator of EteRNA, an online video game in which players solve puzzles that also happen to mimic the way strands of the stuff will behave in nature.

The game has become a digital breeding ground for a stable of citizen scientists as apt to publish their findings in a scientific journal as they are to share a virtual high-five over a high score. And that's surprised even him.

EteRNA is one of a small but growing cadre of games that seek to deploy video gamers -- virtually none of whom have backgrounds in the sciences -- to help solve riddles that could lead to major medical breakthroughs.

It's one of those increasingly common spaces in which gaming meets real life, challenging any stereotype you might have of video game enthusiasts with tired eyes and Cheetos-stained fingers zoning out in front of a monitor while gunning down mutant aliens.

For example, how about cracking the code on an AIDS-related virus that had stumped scientists for well over a decade?

Players of Foldit, the game from which EteRNA emerged, did that just last year. Instead of RNA, they focus on protein molecules. And they deciphered the structure of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus -- which had stumped scientists for 15 years -- in just 10 days.

Not that all of them have a full grasp on the finer points of the discovery.

"They're all orange and blue thingies to me," laughs Doreen DeSorbo, a semi-retired 61-year-old living in Rhode Island, referring to the game's puzzle pieces. "That's the way it is and that's the way it's going to be."

DeSorbo's not much of a video gamer by nature -- although, to her credit, she did try out the uber-addictive fantasy World of Warcraft for about a week at her son's behest.

But she's always loved puzzles and she's become one of Foldit's top 20 players. She said she loves the community that's formed around the game's challenges, the way teams compete fiercely but still cheer when an opponent makes a particularly advanced discovery.

And there's a more personal inspiration, too.

"My mother died of an Alzheimer's-related disease a year-and-a-half ago," she said. "In the back of my mind, I always think, 'Gee … if there's a genetic component to that, maybe what I'm doing today will contribute to something so, 20 years from now, that's not what happens to me."

Adrien Treuille is an assistant professor of computer science and robotics at Carnegie Mellon University. He's also one of the creators of Foldit and he said DeSorbo's feelings aren't unusual.

"An interesting thing we noticed, especially when designing EteRNA, was that the more 'science-y' we made the game, the more people wanted to play it," he said. "That flew against our assumptions. It can be easy sometimes, as a professional scientist, to forget just how romantic the scientific project can be for outsiders."

Foldit and EteRNA both got their start at the University of Washington, where Das and Truielle were post-doctoral fellows.

Das was researching ways that computers could better be used to decipher the codes of RNA while Truielle sat next to him, helping build the game that would become Foldit.

"I wasn't really into it, honestly," said Das, who despite that was asked to lend some of the same coding skills he used on that failed Contra effort. "I thought that it wasn't really science."

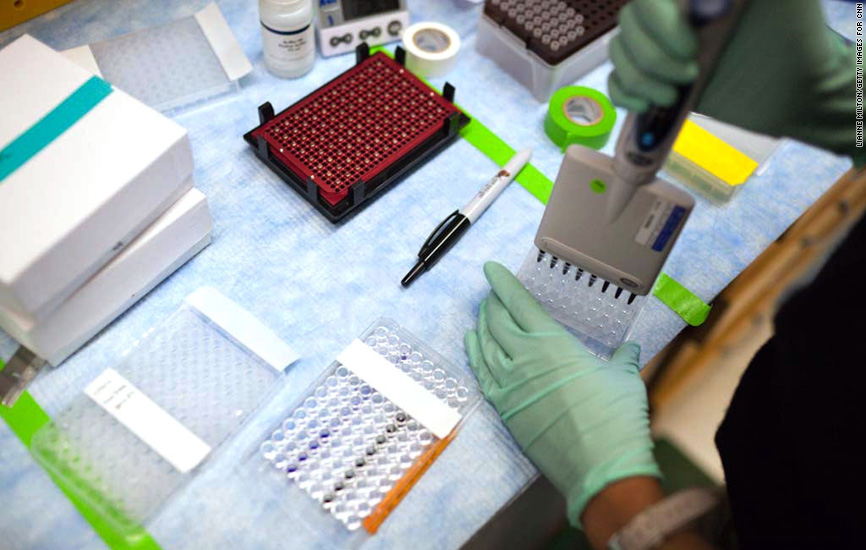

He came around, of course, and, eventually, the two of them helped spin off EteRNA. Now, every week, scientists in Das' lab take the best results from winning puzzles and turn them into real-world strands of RNA -- strands that wouldn't have existed otherwise and which, some day, might provide fodder for a researcher on the verge of solving one of the world's medical mysteries.

The value of the players' contributions, Das said, boils down to human intuition.

Scientists have built computer programs to decipher and build new strands of RNA. But none, he said, can pick up on the subtle, emerging patterns quite like a dedicated human brain. In short, a computer algorithm may be good at telling you what's already happened. But unlike a curious human, it will be really bad at guessing what's going to happen next.

"We're relying on humans to do something computers can't do, which is create hypotheses," Das said. "There's no computer who can do that. They don't have imaginations."

For all of the sometimes mind-boggling advances society has seen in medical science, Treuille believes that researchers in some ways are still at a very basic starting point.

"Biochemists today are akin to our ancestors gazing at birds and wondering how to build flying contraptions, except that we're peering inside the cell," he said.

"What we see -- the dance of proteins which gives rise to life -- is so amazing that scientists have become convinced that understanding protein folding will enable us to control life at the cellular level, which is, of course, exactly what we need to do to attack big medical problems like cancer."

Two years after it formed, EteRNA has about 40,000 registered players (Foldit has a heftier 240,000 or so, although not all of either game's player base is active). Das estimates that about 100 make up EteRNA's elite, the players who have gone from mere puzzling to helping code a computer algorithm which he said "beats the pants off of" any that existed before. He even plans to begin submitting their work as scholarly research.

So, why couldn't Das have just put out an open call for people to help do science? Why go to the trouble of creating a game when the interests of these citizen-scientists have clearly gone beyond high scores?

"The most addictive online experiences, they have certain qualities that are game-like," he said. "They're social. You have a chat. You feel like you're in there with some other people and it also has to give you a huge amount of positive feedback.

"When a player solves a little training puzzle in EteRNA, they get all these bubbles and lights."

In game-creation terms, that's called "juiciness." And when you need to attract a crowd, the juicier the better.

"That was critical for getting folks in the door and to the point where they get to the lab and they realize, 'Oh … I love science!' " he said. "You need to have a critical mass of people before you find the subset who are going to push the project forward.

"Let's say it's .1%. If you only have 200 people sign up, you're going to have a fraction of a person but, if you have 20,000 or 100,000, you have that critical mass."

Enter Eli Fisker.

Fisker is 35, lives in Denmark, and is a librarian who has worked on and off between stretches of unemployment.

He has no scientific background to speak of and only got Internet access at home a little over two years ago.

And he's EteRNA's top player. But not only is he ranked the best at solving the puzzles that become new RNA strands. Fisker is also one of a cadre of players who pore over hardcore lab data and are helping craft a computer algorithm that might one day be as good as the game's best players.

"I got Internet and remembered hearing about common people contributing computer resources to science projects," he said. "I thought, hey, I might not be able to solve my own problems, but at least it will feel good trying to do something that could help others."

And on top of not being a trained scientist, he said that, outside EteRNA, he's not even all that serious of a video gamer.

"I have a PlayStation 2, but mainly I use it to watch DVDs," he said. But he does like puzzle games like Tetris and Bejeweled, along with Ratchet & Clank, a cartoon-like shooter featuring fantastical weapons, humorous dialog and outer-space adventures.

"I admit Ratchet and Clank was a bit out of the theme, (but) I liked the collecting stuff for building weapons, the shooting and all the happy colors," he said. "If a friend had not introduced me to the game, I would never have bought a PlayStation."

Fisker said his favorite part of EteRNA puzzle-solving is the moment he recognizes the recurring themes in the music that the RNA molecules dance to as they form a particular shape. But he also truly enjoys poring over lab data after his games are over, trying to find themes, not just in the puzzles themselves, but in the field of RNA-folding as a whole.

And what if all of that gameplay one day helps lead to a medical breakthrough of some kind?

"If something of what I have made ... would someday help cure a disease," Fisker said, "I would sit with a smile in front of my computer and think: Mission accomplished."