Oakland, California (CNN) -- When 14-year-old Benjamin Ring walks his dog, Jasper, he earns 200 points. When he runs a mile, he gets 500 points. If he hikes with his family or walks to school, he racks up "pointz" that he can redeem for prizes.

"It's like a real-life upgrade," the eighth-grader from Piedmont, California, said about the game Zamzee.

So far, the bespectacled teenager has 47,074 pointz which he has redeemed for Legos and $150 worth of Best Buy gift cards.

Benjamin, a lean and lanky adolescent with bowl-cut hair, is not on a weight-loss program. But he readily says the game has made him more invested in physical activity.

"It made me more interested in exercise because I got money," he said. "I wanted to walk the dog and run as much as I could for PE."

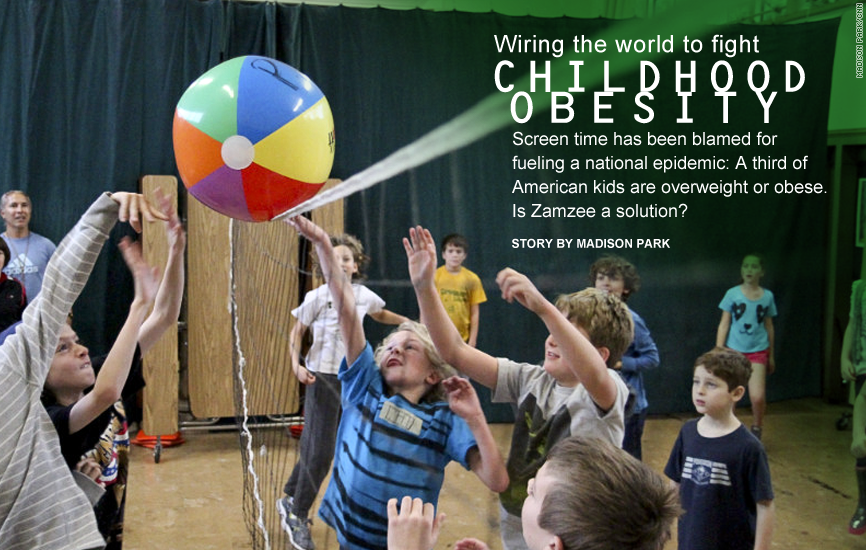

Gaming and screen time have been blamed for contributing to the childhood obesity epidemic, with about one out of three U.S. kids overweight or obese. But there is growing interest in using the addictive, entertainment value of gaming to promote health -- for kids and adults.

"The thinking was, how can we use games for good?" said Fred Dillon, director of product development at Hopelab/Zamzee. "It's obvious kids really like games. Is there a way to take things that kids are already doing and power them for good and health?"

Zamzee tries to instill behavior changes by rewarding exercise and teaching healthy habits. It blends the real world and online experience, because when Benjamin moves in the real world, that movement racks up points for his avatar and allows him to compete against his peers for the most physical activity.

An accelerometer clipped to Benjamin's jeans monitors his moderate to vigorous activity. When he loads data from this device through a USB port into his computer, it shows how much activity he has had since his last login. He can compare how he's doing with other kids. He ranks 53rd among about 3,000 competitors in accumulated lifetime points.

Zamzee, which is expected to become available to the public this fall, is the product of a nonprofit called Hopelab, created by Pam Omidyar. Omidyar, who is married to eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, first used video gaming to help young cancer patients. Hopelab created the 2005 game Re-Mission, in which a heroine travels through the bodies of fictional patients to destroy cancer cells. The video game helped young patients stick with their treatments and improved their cancer knowledge, according to a study published in the journal Pediatrics.

Then the group turned to the problem of childhood obesity. With Zamzee, the idea is to get the kids moving.

"We're hoping that this is igniting a desire to move for the rest of their lives," said Richard Tate, Hopelab's vice president of communications and marketing.

Health researchers want to reach kids and tweens like Benjamin and help them form healthier habits. But competition for their attention is fierce.

Benjamin would rather sit in front of his computer building shelters and contraptions to keep out the monsters on the game, Minecraft, than exercise outside.

"I don't like sports," he said, with a shrug.

Benjamin was asked to participate in the testing phase of Zamzee through a neighbor involved with the project.

His dad, Jonathon Ring said, "I was secretly hoping that it might motivate him to get outside, with his friends and go to the park instead of just sitting on his butt."

"Which I do," Benjamin chimed in.

"I definitely like hiking," he said. "It's one of my favorite things. I think it came out of this."

His dad agrees. Since Benjamin's introduction to Zamzee four years ago, Ring has noticed changes in his son's activity.

"The resistance has gone down," he said, about spending time outdoors.

The concept of getting paid to exercise was a no-brainer for the teenager. "I'm constantly winning things," Benjamin said. "The fact that the prizes are real life prizes -- money, shirts and things that aren't going to be gone when you turn off computer monitor -- there's more interest."

At an Oakland school that is testing Zamzee clips, the gym teacher asked his fifth- and fourth-grade students which ones remembered to wear their activity monitors. Only two kids in each class raised their hands.

They jostled against each other, reaching to slam a volleyball, regardless of whether they remembered to wear their Zamzee or not.

"Part of the challenges for health educators is that they have to be able to capture people's attention and engage before they can change anything," said Amy Shirong Lu, an assistant professor in communications at Northwestern University.

Well-intentioned researchers design health games to change behavior, but often fail to retain interest. Lu demonstrated games designed to promote health or political engagement to her video gaming classes when she taught at Indiana University last year. But for a generation who grew up fighting for humanity against invading aliens on Halo or fending off Nazis on Call of Duty, the didactic games weren't terribly impressive. About 50% to 60% of the time, they were bored with the behavior-change games, Lu said.

"When we looked for good video games combining education and entertainment value, it's hard to find a lot out there," she said.

She showed her students nutrition-related games produced by companies like Dole and one by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dole's Go Bananas game teaches kids about nutrition by having an animated banana catch falling foods, differentiating between junk food and healthy foods. USDA's MyPyramid Blast Off game has the player pick nutritious foods to fuel a rocket launch.

"It's trying to give you knowledge," Lu said. "Knowledge doesn't change behavior at all."

Most health games tend to fail when they resemble a lecture, said Lee Sheldon, an associate professor and co-director of the Games and Simulation Arts and Sciences program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

"The mistake they're making in game design is they're being too literal," he said. "I think we have to strike a balance between entertainment and pedagogy."

A survey released in May by the health care company UnitedHealth Group found that adult consumers want to incorporate gaming into their health routines. Nearly 75% of the 1,015 adults surveyed said video games should encourage physical activity.

An app called Zombierun available on the iPhone gives detailed stories and instructions in which runners follow a plot and attempt to evade zombies during a jog.

In 2009, Indiana University experimented with a game called Skeleton Chase that forced freshmen to crisscross the campus trying to gather clues and solve a mystery. The alternate reality game lasted for eight weeks. The plot centered on a missing professor, evasive witnesses and clues scattered throughout the Bloomington, Indiana, campus. Sheldon created a fake website and had actors portraying different characters who would give the students clues.

"The idea was simply that the students would do a lot of running, geocaching, sprints," he said.

The game forced students to move constantly. They learned it was quicker to get across campus by walking rather than taking the bus. The game was plot-driven, rather than activity-driven like Wii Sports or Dance, Dance Revolution, said Sheldon, who wrote "The Multiplayer Classroom: Designing Coursework as a Game."

"They became so involved in the game, they were becoming fitter without realizing it."