Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in CNN’s Meanwhile in America, the email about US politics for global readers.

Next year will bring new strains to the transatlantic alliance, with the return of Donald Trump to the White House.

The president-elect is certain to pile even more pressure on European nations to increase their spending on defense — and may use the threat of downgrading US support for NATO as leverage. And given the threat from Russia and rising global instability, he may well have a point.

Trump spoke again this week about his desire to quickly end the war in Ukraine and is already talking about ending Russian President Vladimir Putin’s alienation from Western leaders by meeting him at an early opportunity.

European nations are, meanwhile, competing to win Trump’s affections and preparing for the storm to come. French President Emmanuel Macron lured Trump to Paris for the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral. Britain has just named Lord Peter Mandelson, one of its most Machiavellian political operators of the last 40 years, as its new ambassador to Washington. Germany is in political turmoil with a new election looming. And Trump prefers the company of leaders who share his populist nationalist creed, like Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán.

It’s been decades since the idea of the “West” has seemed so tenuous. The foundations for the post-World War II global order were laid by President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill during World War II. And Christmas Eve always brings memories of Churchill’s important trip to Washington shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that pushed the US into World War II in December 1941.

We first featured this meeting in Meanwhile on Christmas Day in 2019. Here’s another chance to read about this pivotal festive season that built a new world.

Even Eleanor Roosevelt didn’t know who was coming for Christmas – though in retrospect her husband’s order for fine champagne, brandy and whiskey might have been a clue.

It was December 1941. World War II had drained the Christmas spirit and the US was in shock, just weeks after Japan’s strike on Pearl Harbor dragged it into the war’s inferno. Roosevelt was in no mood for house guests, but Winston Churchill bullied an invitation anyway. Soon, the British prime minister was aboard HMS Duke of York, dodging U-boats and plowing across the wintery Atlantic.

A plane whisked his contingent from Virginia’s coast to Washington, DC, and the British, used to London’s air raid blackouts, marveled at the lights of the city below, decked out for its first wartime Christmas.

The first lady learned the identify of her guest only when he was in the car on the way to the White House – with the veil of secrecy lifted with Churchill safe on US soil. What came next was the most remarkable summit in White House history. It came at a moment when humanity was in crisis, with tyranny and bigotry on the march. And it showed that leadership, from two giants equal to their moment in history, could make the world safe for freedom and democracy – no matter how dark the hour during the grim days of that long-ago Christmas.

Churchill was not an easy guest given his idiosyncrasies – afternoon naps, late-night brainstorming, and a habit of parading around in various states of undress. He told FDR’s butler he needed a tumbler of sherry with breakfast, Scotch and sodas for lunch, champagne in the evening and a tipple of 90-year-old brandy for a nightcap.

Years later, Eleanor Roosevelt would express astonishment at the cigar-puffing Churchill’s iron constitution. “Like all Englishmen, he was very fond of beef in any form,” she noted. Even FDR’s notoriously awful cook couldn’t scare off the British as they devoured fresh eggs and oranges denied them by years of rationing back home.

There were bigger differences, too. Roosevelt despised the British Empire, which Churchill adored. American generals in attendance found their visitors snooty. The British brass, hardened by years of defeats, thought the US side naive.

But two weeks together would eventually forge a bond and create the blueprint to win the war: Roosevelt and Churchill eventually inked a Europe-first strategy to defeat the Nazis before imperial Japan and a joint move on North Africa.

They would also agree on the United Nations Declaration, meant to spare future generations from the horror of war and to unite the West with institutions and a common transatlantic mission – one that could again be at risk when Trump re-enters the Oval Office.

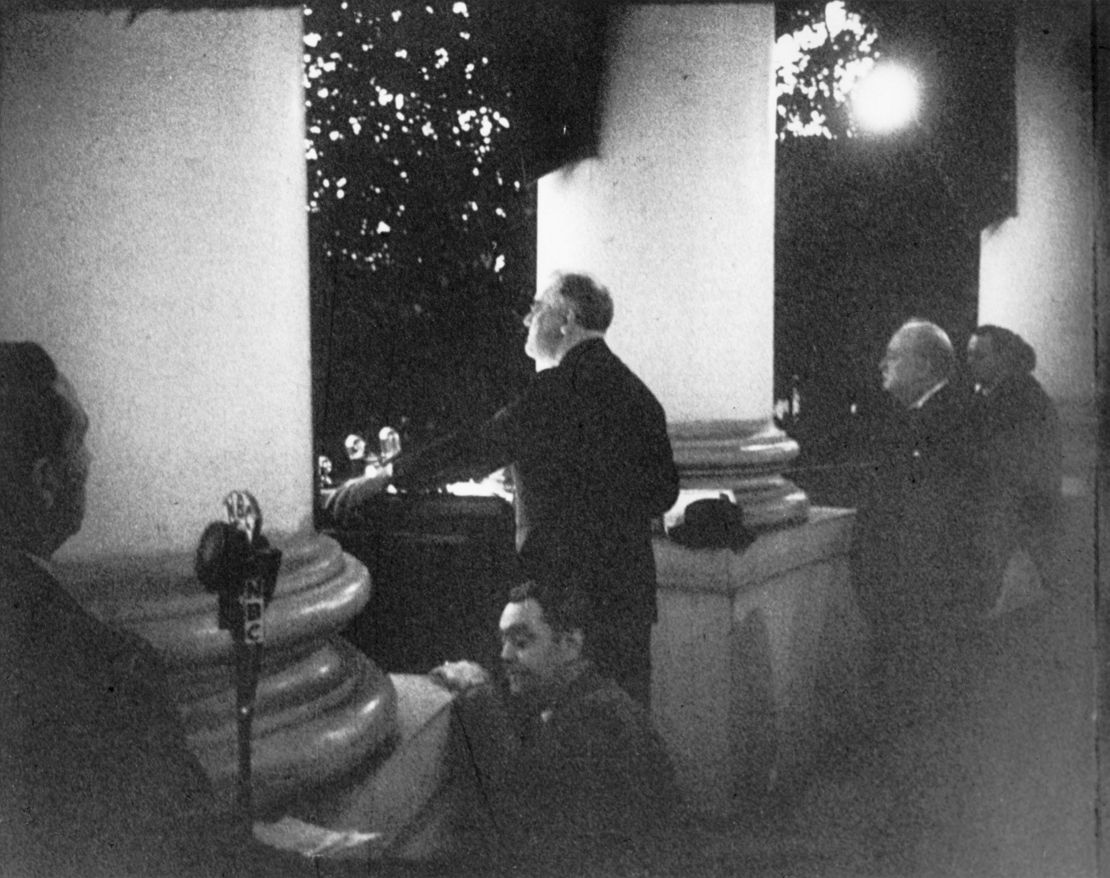

On Christmas Eve, Churchill stood by as Roosevelt flipped a switch to light the National Christmas tree.

“How can we give our gifts? How can we meet and worship with love and with uplifted spirit and heart in a world at war, a world of fighting and suffering and death?” Roosevelt asked. He answered his own question, urging Americans to use the holiday season to muster for the fight ahead with “the arming of our hearts.”

“And when we make ready our hearts for the labor and the suffering and the ultimate victory which lie ahead, then we observe Christmas Day – with all of its memories and all of its meanings – as we should.”

Churchill, whose mother was American and who traveled to the US in his “wilderness years,” when he was out of power in the 1930s, said: “I spend this anniversary and festival far from my country, far from my family, and yet I cannot truthfully say that I feel far from home.”

“I feel a sense of unity and fraternal association which, added to the kindliness of your welcome, convinces me that I have a right to sit at your fireside and share your Christmas joys.”