With Formula One cars rocketing around Lusail International Circuit at average speeds comfortably north of 130 miles per hour (210 kilometers per hour), the Qatar Grand Prix was all over in little more than 90 minutes.

Yet even while the checkered flag waves and fireworks light up the Doha skyline, hundreds of staff scuttle around the 10 respective team garages as they start a race of their own to transport the entire operation to Abu Dhabi in a matter of days for the next Grand Prix.

In a meticulously technical sport spanning 24 races, 21 countries and five continents across nine months of 2024, it is a unique and dizzying logistical challenge only further complicated by the sweeping fan, hospitality and entertainment extravaganza that follows in its wake.

“We call it the circus. It really is a traveling family,” F1 chief communications and corporate relations officer Liam Parker told CNN.

“We’re everywhere, and that’s what makes it special. It really is a global sporting spectacular … It’s not just racing anymore – it’s entertainment, it’s music, it’s celebrity.”

Even after a decade of reporting on the sport, PA Media’s F1 correspondent Phil Duncan still marvels at how teams cope.

“We’re talking about as many as 4,000 people (team staff) traveling to all the different races,” Duncan told CNN.

“How they manage to transport all the people around the world, all the hardware, the cars, the machinery, the parts – it’s quite a remarkable achievement.”

Pressure

So, to take the Qatar Grand Prix as a case study, just how do they do it?

It’s certainly not by getting plenty of sleep, insists Aston Martin race team coordinator Joe Micklewright, a former sous chef whose myriad responsibilities on race week began the second he arrived – bleary-eyed – in Doha on Monday following a 17-hour flight.

Lusail International Circuit marked the middle leg of a triple-header – three race weekends in a row – to close out the 2024 season, sandwiched between Las Vegas and the final Grand Prix in Abu Dhabi on December 8.

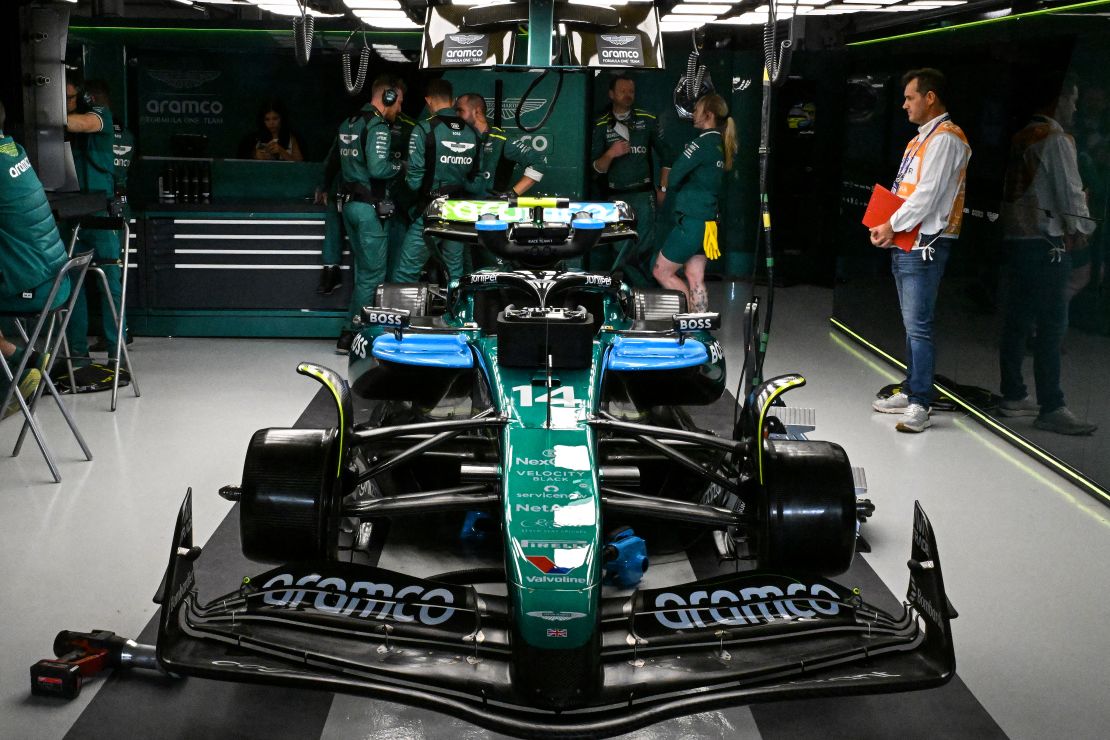

After snagging a few hours of sleep, Micklewright awoke Tuesday morning to meet the air freight carrying some 25 tons of essential cargo – including the two cars – that he had arranged to follow him some 8,000 miles from the US.

And that’s not to mention enough tables, chairs and other pieces of less critical garage equipment to fill five separate shipping containers that arrive via sea freight. Aston Martin alternates six sets of such containers globally in order to reach all 24 races in time, with the Doha shipment already en route to Australia for the 2025 curtain-raiser in March.

That all adds up to approximately 50 tons of freight transported to every Grand Prix by each team.

With such tight deadlines – including a strict curfew that restricts the amount of time staff can work on the cars on a Wednesday and Thursday of a race week (roughly 12 hours each day) – even the most minor of travel complications can be acutely damaging.

“We do have a lot of pressure,” said Micklewright, adding that a customs delay led to the air freight arriving almost four hours late to Doha.

“We’ve got to get the right equipment to the right place at the right time and our paperwork has got to be up to scratch. Otherwise, it all just creates delays and that just has a knock-on effect all the time.”

Assembly of the cars, each comprising some 5,000 components, begins Wednesday as the garage is assembled around it in order to be fully functional by Thursday.

On Friday, Saturday and Sunday – practice, qualifying and the Grand Prix respectively – Micklewright is part of the crew tasked with looking after driver Fernando Alonso’s tires, even getting involved in pit stops if required.

This role is simply one more paragraph on his extensive job description, with Micklewright’s other duties including maintenance of the garage, handling any ad hoc team issues with hotels or car hire, and liaising with some of the roughly 800 staff back at team headquarters in Silverstone, England.

As jet lag compounds the general fatigue of a globetrotting campaign that began in earnest with the unveiling of the 2024 car in February, leaning on the support of the “traveling family” is paramount.

“It does take a toll on you, especially at the end of the season. You do get quite tired,” Micklewright admitted.

“When things aren’t going well, you’ve got to stick together, put your arm around each other and make sure you just get through it. You’ve just got to keep going.”

‘There’s no better feeling’

It’s a sentiment echoed by Micklewright’s logistical counterpart at rival team Haas, trackside operations manager Neil Hanley.

With less than 300 total staff spread across England, Italy and the US, Haas are the smallest team on the grid, according to Hanley, who begins drawing up schematics for the garage six weeks before each race.

Such foreplanning is essential given the comparative lack of personnel, but what Haas – currently seventh in the Constructors’ Championship – lacks in numbers it makes up for in heart and camaraderie, Hanley insists.

“They are just a great bunch of people,” he told CNN.

“It starts even from the catering team, our logistics suppliers. Without them, we wouldn’t be where we are. We wouldn’t get those points without the mechanics on the ground … without the engineering departments, without the management and the engineers and the drivers, if we didn’t work as a cohesive team.”

“Sunday night when that checkered flag goes down, if we’ve got one or two cars in the points – there’s no better feeling,” he added.

That flag drop signals the start of a mad dash to totally disassemble the garage and pack all the equipment onto their respective freights, an operation that extended well into early Monday morning in Doha.

Past the halfway mark of a “brutal” triple-header, it is only when Hanley boards a plane bound for Abu Dhabi a couple of hours later – blissfully uncontactable – that he can catch his breath.

That’s until landing, when the circus reopens again.

“It doesn’t stop,” Hanley said. “We can’t just say its the hours at one race – it’s hundreds, thousands of hours just to get these cars on the ground. Twelve hours a day, seven days a week at one event.

“Those sat (watching) on the sofas, who haven’t got family members or loved ones within a team, probably wouldn’t see or know the amount of time we spend on the road.”