Editor’s Note: Examining clothes through the ages, Dress Codes is a new series investigating how the rules of fashion have influenced different cultural arenas — and your closet.

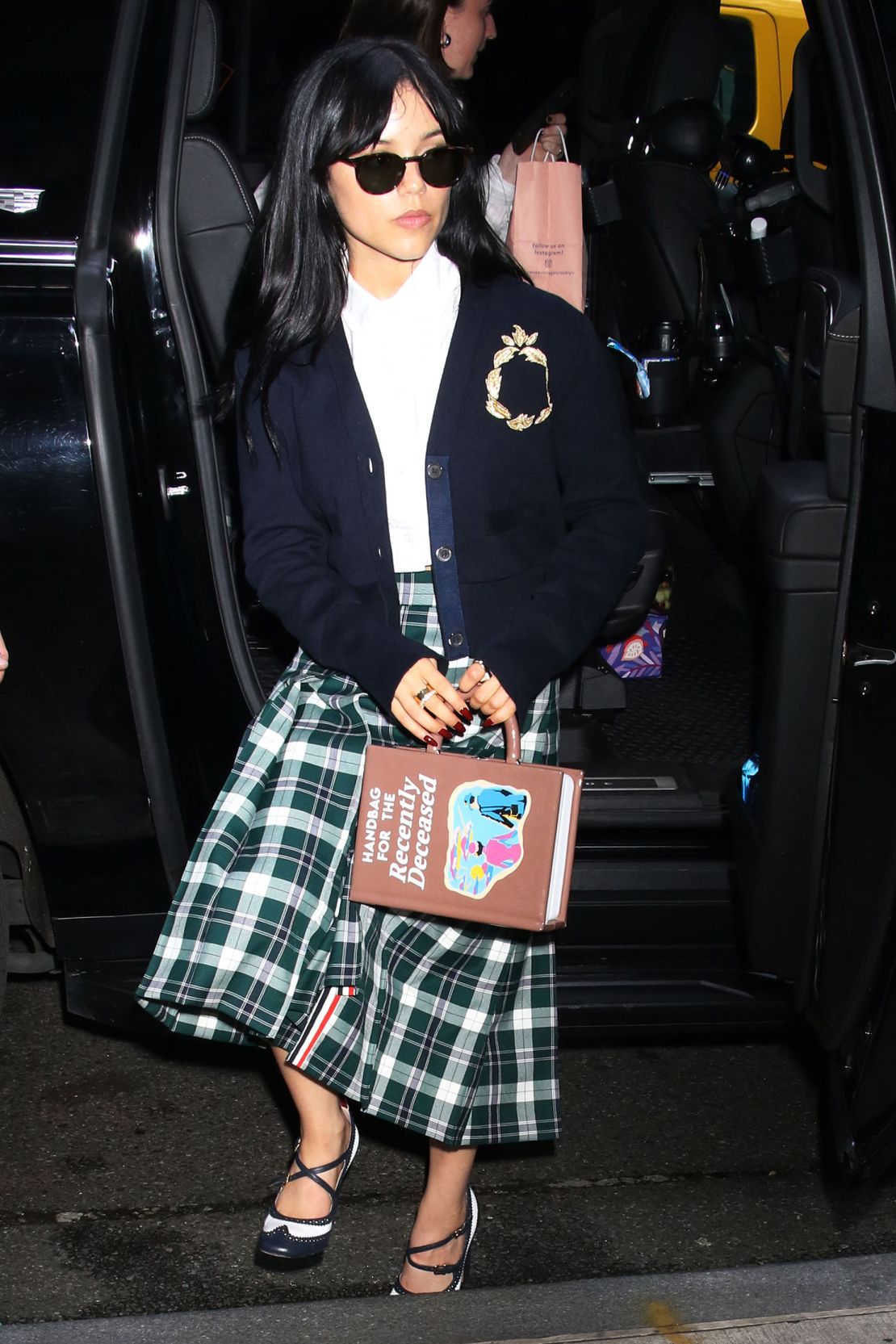

As students return to school, one patterned textile now synonymous with uniforms will make its seasonal reappearance on pleated skirts, jumpers and ties: plaid. The design has long been a mainstay in both classrooms and in pop culture, bringing to mind the hilarious Irish teens of “Derry Girls,” the bold ‘90s fashion of “Clueless” or the provocative outfits of the early 2000s pop duo t.A.T.u.

Plaid has become a catch-all term in the US, but includes patterns with distinct histories, including tartan, from Scotland, which is more associated with Catholic school uniforms, and madras, from India, which became a staple of American collegiate prep looks popularized by the likes of Ralph Lauren and Brooks Brothers in the latter half of the 20th century. It’s a family of textiles with broad scholarly appeal, with both religious and secular schools worldwide incorporating plaid into uniforms, from Mexico to Japan to Australia.

But how did a cloth like tartan, once the symbol of Scottish Highlander identity and rebellion, wind up on the fictional American teen Cher Horowitz as the ultimate twist on schoolgirl fashion? The reasons for the wool textile’s success as both a national identity marker and school dress code are one and the same.

“It really communicates a sense of belonging,” said Mhairi Maxwell, co-curator of the exhibition “Tartan,” which showed at the V&A museum in Dundee, Scotland, last year. “Any club, any society, any school, can design their own tartan. You’re part of this larger club, but you’re also your own little clique within it.”

Thousands of variations have been officially added to the Scottish Register of Tartans, making it a pattern that both follows strict rules and allows for “infinite possibilities” in design, Maxwell explained. There’s the highly recognizable red, blue, green, white and yellow weaves of the Royal Stewart (or Stuart) tartan — both the official tartan of the British monarchy and one of the most popular variations adopted by the punk movement — the blues and pinks of Vivienne Westwood’s MacAndreas tartan, worn by Naomi Campbell in the 1990s; and the crimson, white and black pattern made official by the University of Alabama in 2011.

Possibly the earliest existing scrap of tartan known today is a 16th-century piece found in a bog in Glen Affric, Scotland, which the V&A Dundee studied before the exhibition. The Scottish Tartans Authority commissioned dye analysis and radiocarbon testing on the textile, which has now been dated to between 1500 and 1600. It’s known that tartan existed for centuries before, though how long is often contested.

“Tartan’s origins are so elusive — it’s really hard to pinpoint (their) origin story,” Maxwell said in a phone interview, noting that many cultures around the world have grid-patterned textiles in their histories, leading to the differing claims of where and when tartan was first woven. The pattern has specific rules, however, that distinguish it from check or gingham patterns as well as madras.

Shifting associations

Tartan’s history within Scotland has been debated as well. Centuries of romanticizing Highlander clanship and identity has likely influenced our contemporary understanding of the textile, Maxwell noted. The popular idea that tartan designs, dyes or techniques were rigid identifiers of a particular community is dubious, she pointed out — the clans weren’t siloed off, but imported and exported their materials.

However, it was the Jacobite military leader Charles Edward Stuart — known as Bonnie Prince Charlie — who made tartan a powerful symbol, leading his tartan-clad forces during an unsuccessful uprising in 1745 to restore his family’s Catholic leadership to the British throne.

“(He) made tartan the plaid of the people, and used it to create a movement to fight for his cause,” Maxwell said. “He was already capitalizing on that idea that it was a cloth of allegiance that bound people together to fight for something they believed in.”

After Stuart’s defeat, tartan was restricted in its use for decades in Scotland through Great Britain’s Dress Act, but it had a fashionable revival in the early 19th century that received royal support, particularly from Queen Victoria. The era saw an “elite appropriation” of Highland craft and lifestyle, Maxwell explained. Previously a formidable sight to encounter on the battlefield, it now represented a different kind of pride in the form of status and wealth, making it an ideal textile to use in schools promoting prestige and heritage.

“I can’t really think of another textile which has all this baggage with it,” Maxwell said. “It’s a traditional cloth, but it’s super rebellious at the same time.” It also became a fabric with imperial implications, as it made its way around the world through the uniforms of Scottish Highland regiments at war, British colonial exports and the transatlantic slave trade.

A collective identity

In the US, tartan was first introduced when the states were still British colonies. But the textile didn’t become a fixture of school uniforms until the 1960s, according to historian and educator Sally Dwyer-McNulty, who authored “Common Threads: A Cultural History of Clothing in American Catholicism” in 2014. That decade saw the textile “explode” in popularity, she explained in a phone interview, brought to market by major Catholic school uniform suppliers at the time, including Bendinger Brothers and Eisenberg and O’Hara (now Flynn O’Hara), who often had contracts with entire networks of diocesan schools.

“It’s like virtuous consumption, where Catholics, like lots of other post-war families, had a little bit more money to spend,” she explained in a phone interview. “The companies that had exclusive contracts wanted to tap into the resources that families had and make the (uniforms) attractive.”

Plaid already had ties to Catholicism, and it also visually stood out, she said. And, like across the pond, it allowed schools to brand themselves through their uniforms with a textile that allowed for a lot of variance without any external adornments.

“It creates this collective identity that’s important. It gives students this kind of embodied pride that they have regarding their school — or they can also express their rejection of that uniformity by letting their socks fall down to their ankles,” she joked. (Dwyer-McNulty herself attended two different Catholic schools in Philadelphia, wearing plaid uniforms through high school).

Uniforms were only associated with parochial and private schools until the late 1980s, but public schools began piloting them as well, allowing plaid’s influence in American classrooms to spread. (President Bill Clinton was a particular proponent of them during his administration the following decade, believing they would help reduce student crime). By the 1990s, the styles were no longer just available by contracted uniform companies, either, Maxwell noted, as stores like Gap and The Children’s Place stocked up on plaid skirts and jumpers.

Globally, plaid has been revived, remixed and deconstructed any number of ways today, as designers, subcultures and television and film continue to play on the trope. For Maxwell, 1995’s “Clueless” remains a favorite interpretation. It’s also one that keeps giving, as the bright yellow plaid skirt-suit set worn by Alicia Silverstone is continually replicated, last year by Kim Kardashian for Halloween, and redesigned by Christian Siriano (and worn by Silverstone) for a Superbowl ad.

“That Valley Girl appropriation of tartan is really cool,” Maxwell said. “It’s playing off that heritage of preppy Ivy League, but flipping it on its head and making quite a feminist statement about what it is to be educated, young and aspirational.”