Editor’s Note: This story contains graphic content.

Tune into The Lead with Jake Tapper for Senior National Correspondent Kyung Lah’s report on this story.

(CNN) – By the time the FBI first showed up at Kevin Patrick Smith’s home in early February, he’d already left dozens of threatening voice messages for US Senator Jon Tester.

“You stand toe to toe with me, I rip your head off. You die.”

FBI agents admonished Smith – who lived about a mile from the Montana Democrat’s office in Kalispell – to stop the threats, which were making the senator’s staff members afraid to come to work. But the middle-aged contractor couldn’t bring himself to stop. After 10 days, he resumed the calls in ramped-up fashion, leaving messages that now alluded to guns.

All said, Smith left about 60 messages for Tester’s office, sometimes over the din of a TV or radio blaring in the background. Aside from some vague accusations (“you’re pedophiles and you’re criminals”), Smith’s threats contained few specifics about why he was so angry.

When FBI agents returned to arrest Smith in late February, they confiscated four shotguns, five rifles, eight pistols, a home-made silencer and nearly 1,200 rounds of ammunition. Smith pleaded guilty to threatening to injure and murder a US Senator and was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison.

His case is but a drop in a tidal wave of menacing behavior in recent years that has rattled the offices of public servants and is on a path to collide with what is shaping up to be the most politically toxic presidential election in modern memory.

CNN reviewed more than 500 federally prosecuted threats. Here's what we found:

- At least 41% of all the cases across the decade were politically motivated.

- Nearly 95% of people prosecuted for making threats to public officials are male; the median age is 37.

- Politically motivated threats to public officials increased 178% during Trump’s presidency.

- Threats related to hot political topics like abortion or police brutality also skyrocketed during the Trump years, increasing by more than 300% from Obama’s second term.

- As the party in power, 16 Democrats received threats during Obama’s second term. This increased 169% with 43 GOP lawmakers threatened under Trump.

As the 2024 campaign revs up – and on the heels of indictments against the Republican frontrunner, former President Donald Trump, who has verbally attacked some of his courtroom adversaries – the ongoing onslaught of violent messages, particularly to federal lawmakers and other public officials, threatens to disrupt the American machinery of government.

Though the threatscape to members of Congress and other public servants appears to have cooled in 2022, this year has seen several flareups that could prove a harbinger. They include a recent burst of threats targeting some GOP holdouts in the failed effort to award far-right Rep. Jim Jordan the House speakership, another surrounding Trump’s indictments, and yet another targeting progressive Rep. Ilhan Omar – who has been historically critical of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians – following the outbreak of the war between Hamas and Israel.

Threats have also recently targeted election officials. Last month, staff in election offices in several states received suspicious letters. One of them, in Washington state, contained fentanyl.

“These are perhaps the most dangerous hate crimes,” said Anne Speckhard, director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism, referring to threats against public officials and election workers. “They’re really scary because they can take down a democracy.”

CNN reviewed more than 540 cases involving people who have been federally charged with making threats against public officials or institutions between January 2013 and November 2023. The analysis includes every prosecuted threat CNN could find against public officials or institutions that was announced by the Offices of the United States Attorneys.

The lion’s share of those names, including Smith’s, were provided by a research group at the University of Nebraska, offering a rare glimpse into the lives of the accused as well as the names and political affiliations of the targeted. The researchers say nearly 80% of the defendants were convicted.

CNN’s analysis – which also includes some cases logged by the Prosecution Project, a database of alleged perpetrators of political violence – shows first and foremost just how rare prosecutions are for people who unleash hostile, abusive or harassing invective at public servants or their family members.

In 2021 – a peak year for the activity – more than 9,600 direct threats and “concerning statements” were leveled against members of Congress, according to the Capitol Police. Another 4,500-plus that year were hurled at judges, attorneys, jurors, and others who are protected by the US Marshals Service.

The datasets reviewed by CNN showed that, in 2021, just 72 threats against public servants or institutions led to federal charges. Of those, about half were threats driven by ideology, which CNN defines as violent statements made against partisan elected officials, presidential appointees, election workers or against professionals – such as doctors, judges, school officials or law enforcement officers – for reasons connected to hot political buttons such as abortion, LGBTQ issues or police brutality. About 40% of all the cases across the decade were politically motivated, CNN found.

(Examples of non-ideological threats include ones where suspects threatened people investigating or adjudicating their cases or threatened to kill people indiscriminately, such as by bombing a school.)

Some threats to public officials are also prosecuted at the state and local levels.

Officials say the vast majority of hostile messages to public servants aren’t actionable, meaning they don’t meet the legal threshold for being prosecuted as threats.

Prosecuting threats could become even more difficult in light of a Supreme Court decision this summer in favor of a Colorado man who argued that his harassing messages to a woman on Facebook – including the phrase “Die. Don’t need you” – weren’t intended as threats and should be protected speech. That 7-2 decision, with Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett dissenting, reversed a lower court’s ruling based on a less rigorous prosecution standard, which maintained that a threat crosses the line if it puts “a reasonable person” in distress.

The Biden administration had weighed in on the case, unsuccessfully arguing in an amicus brief that further raising the bar for prosecuting threats could frustrate the ability of public officials to carry out their duties at a time of heightened political rhetoric.

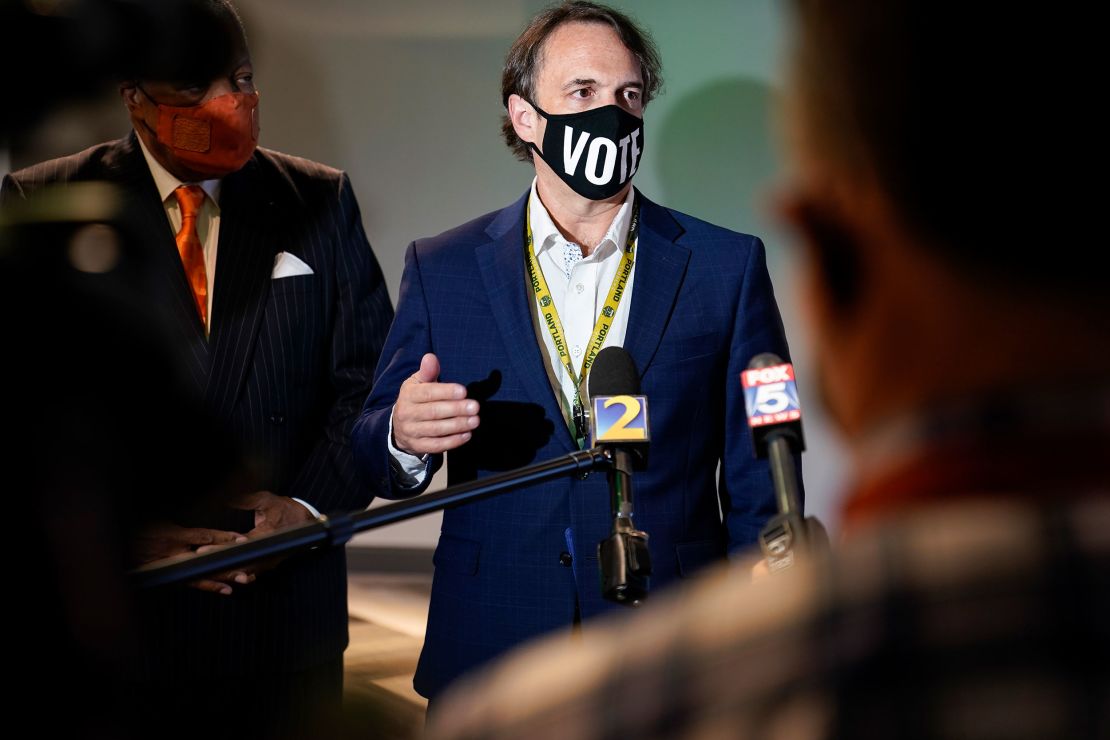

Richard Barron, a former election official in Georgia, received hundreds of vitriolic and threatening messages after the 2020 election, when Trump lasered in on the state during his failed bid to claim fraud.

A state attorney general spokesperson told CNN that none of the threats to election officials in Georgia that were referred to and reviewed by the office “rose to the level of criminal conduct or no suspect could be identified” and no charges were filed.

“I think Trump gave everyone a license just to say whatever they wanted, make whatever threats they wanted,” Barron told CNN. “I think they knew they wouldn’t get punished for it.”

In one voicemail provided to CNN, a man who believed the election was stolen made reference to “Caucasian” founding fathers and said Barron – who is White but managed a majority-Black staff – deserved to be shot or “served lead.”

Barron said the threats – along with a GOP-led effort to undermine his office – played a role in his decision to resign as the elections director in Fulton County in the spring of 2022.

“My daughter became worried about me,” he told CNN. “My condo has floor-to-ceiling windows and she didn’t want me near the windows where they are overlooking the street.”

Barron added that two agents did interview him about the “served lead” threat, but said he hasn’t heard any updates since his departure. John Keller, an official with the election task force established by the DOJ in 2021, told CNN that the hostile message does seem to “meet the definition of a true threat,” but that he couldn’t comment on cases in which charges haven’t been filed. The spokesperson for the Georgia attorney general said the office didn’t receive any information about that particular threat.

Katherine Keneally, head of threat analysis and prevention at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, said threats to public officials are under-prosecuted. She believes this is due in part to a “resource-strapped” Department of Justice, as well as the challenge of assessing when a threat crosses a line into speech that isn’t protected by the First Amendment.

“It’s incredibly difficult, and I do not envy the DOJ’s position,” she said.

Though prosecutions are comparatively rare, they are up as well, having risen roughly in synch with the explosion in violent and vitriolic rhetoric overall.

CNN’s analysis found that the number of ideologically driven threats against public officials that led to federal charges skyrocketed during the presidency of Donald Trump, nearly tripling the number of threats that were prosecuted during the final term of President Barack Obama (when the dataset begins). The number of threats that led to arrests peaked in 2021 – with more than 40% that year happening in January prior to President Joe Biden’s inauguration – before dropping in 2022.

These figures don’t include ideologically or racially motivated threats or acts of violence that target fellow citizens, which have also been on the rise. In the wake of the unfolding crisis in Israel and Gaza, US officials have warned that such threats against Muslims and Jews have spiked; authorities are also on high alert for possible terrorist activity.

Threats of violence against public officials or their families not only terrify people, they also play havoc with the legislative process. Jordan’s supporters tormented his moderate GOP colleagues in October in what some said was a concerted campaign to “attack” and pressure the holdouts into voting for Jordan’s ill-fated speakership bid.

CNN’s analysis found that in recent years threats of this nature have become more targeted.

During Obama’s second term, politically motivated threats to public officials that led to federal arrests were less likely to name names. And when they did, they tended to name Obama himself.

Between 2013 and January 19, 2017, the sitting president – Obama – was the target in 71% of all such threats against named public officials, CNN found. During Trump’s tenure, threats to the president fell to 24% of the total to public officials; so far under Biden’s, it’s 19%.

Conversely, the number of named partisan targets quadrupled during the Trump era, with threats singling out all levels of public officials, from members of Congress to state election officials to governors and city council candidates. That trend has continued into the Biden presidency.

After Trump took office, threats to members of both parties rose sharply.

More Republican officials – who were almost never singled out during Obama’s second term – were targeted than Democrats in prosecuted threats during the Trump years (43 Republicans targeted vs. 35 Democrats). However, the number of Democrats who were threatened during Obama’s term – 16 – more than doubled under Trump.

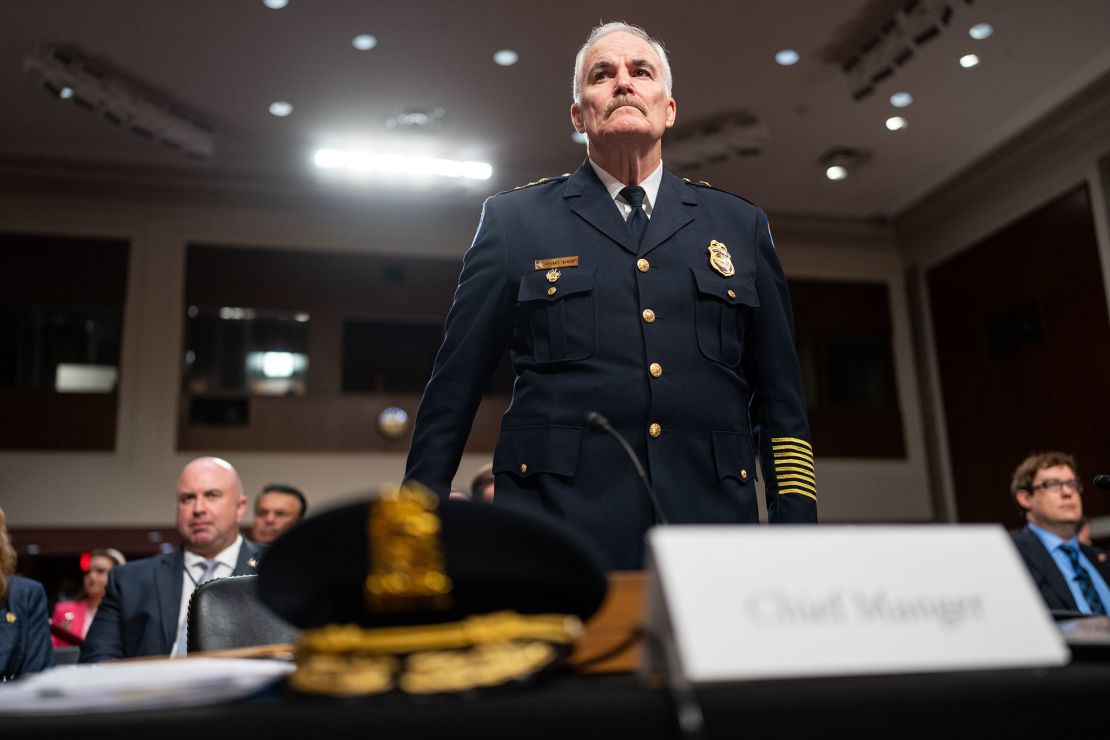

US Capitol Police Chief Thomas Manger told CNN that threats to certain members of Congress often seem to come on the heels of media stories about them.

“Any time a member of Congress is in the news, whether it’s good or bad or just neutral … you will see a spike in threats to that individual member,” he said. “It just gets people to notice.”

As president, Biden has borne the brunt of threats lobbed at Democrats, though he’s on pace to receive significantly fewer prosecuted threats than each of his two predecessors.

During the combined Trump and Biden eras, Republicans and Democrats were targeted almost evenly: 82 threats leveled at named Republican officials and 80 threats against named Democrats led to federal charges, CNN found.

The GOP tends to take fire from both sides, as the Trump years gave way to a lasting surge of threats against members of their own party often labeled as RINO, a term embraced by Trump supporters that means “Republican in name only.” Still, in the cases examined by CNN, it was more common for members of the GOP to be verbally attacked by people whose politics appear to be to their targets’ left.

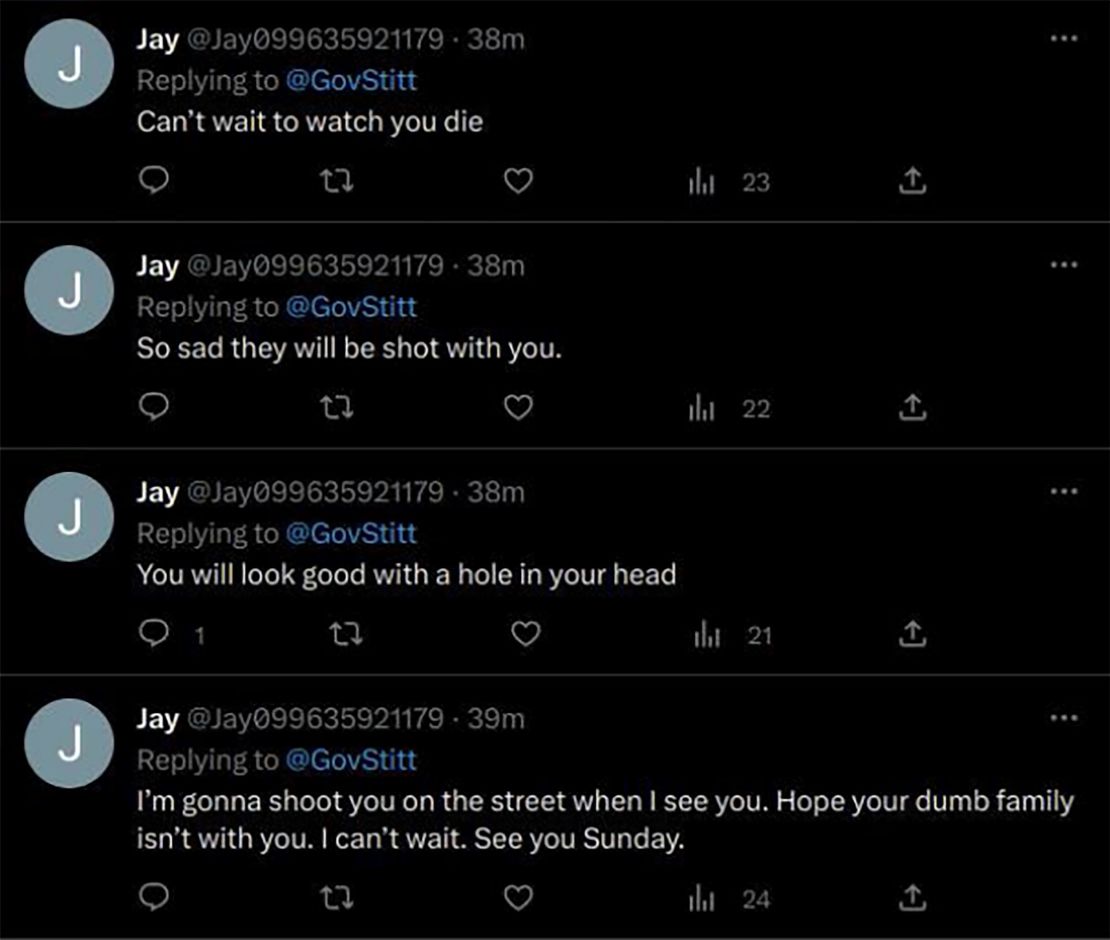

One incident happened in May, when an Oklahoma man went on an 11-minute trolling rampage against Republicans on Twitter, now known as X, that landed him in prison for a year.

On the evening of May 15, Tyler Jay Marshall, then 36, posted threatening messages to the Twitter accounts of Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders and US Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas that caught the attention of the Oklahoma Information Fusion Center, a criminal intelligence taskforce, which notified the FBI.

Marshall, who registered as a Democrat in 2021 and whose Twitter account was created with the email address gopshoulddiesoon@gmail.com, also tweeted a threat at Florida governor and GOP presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis.

Marshall, whose lawyer told the court that he does not own a gun, pleaded guilty and was sentenced in mid-October to a year in prison.

The attorney, Tyler Box, told CNN that Marshall – who is in federal custody – is a veteran who’d been discharged from the military due to an injury, had recently gotten divorced at the time of the incident and developed a severe drinking problem.

“When he would get very intoxicated, he would vent online,” Box said.

A judge wrote that Marshall also displayed signs of having an “extreme mental health crisis.”

CNN found that the prosecuted threats to US presidents tend to be less coherently partisan than the prosecuted threats made to members of Congress and other politicians. For instance, at least four of the 30 perpetrators charged with threatening Trump during his presidency had also threatened Obama; another also threatened Biden. About a third of the 32 perpetrators who threatened Obama did so while incarcerated; another fifth had documented mental health issues, CNN found.

Threat perpetrators often argue that they are exercising their freedom of speech. One of them emailed with a CNN reporter from prison on condition that he not be named due to fears for his safety. That offender views himself as a political prisoner and claims his due-process rights were violated.

“At (t)he end of the day I am in prison for WORDS in a country tha(t) pretends to have a first amendment and care about its laws,” he said. “For this reason I no longer trust my government and am scared for my life and the lives of my family if I speek (sic) out.”

Common traits of threat-makers

When it comes to which cases are prosecutable, the specificity of the threat matters – as does the intent of the perpetrator, and the impact it has on the victim. Threats that are more generalized or non-credible often fall within the bounds of protected political speech.

“’I’m going to kill you at 12:01’ versus ‘I’m going to kill you,’” said Seamus Hughes, a senior researcher with the project at the University of Nebraska. “If you got a good lawyer, you’re off on the second one.”

Smith, who made threats to Tester, the Montana Democratic senator, embodies a few common characteristics of the threat perpetrators examined by CNN. As a 45-year-old who made the threats, he was actually a little older than most perpetrators in the dataset, where the median age was 37.

But like dozens of the perpetrators examined by CNN, he was grappling with mental health issues. Smith also was still reeling from a contentious and bitter divorce. Divorce – along with loss of loved ones, solitude and substance abuse – was another recurring theme in the lives of many offenders.

The vast majority of the culprits – more than 90% – are male.

Quite a few, like Smith, continued to make threats even after being warned by law enforcement to knock it off.

One high-profile case this summer involved Craig Robertson, a 75-year-old widower from Utah who brazenly ignored warnings by the FBI to stop making threats online against Trump’s adversaries.

Instead, the avid collector of assault rifles and other guns went on to post a barrage of detailed death threats – often alongside photos of firearms – against public officials, including Biden ahead of a presidential trip to the Beehive State.

The threats to Biden prompted another visit from the FBI that turned tragic when an agent fatally shot Robertson after he allegedly aimed a gun at them.

A similar but lesser-known case began in early 2020, when FBI agents were alerted to disturbing voicemail death threats against California Rep. Adam Schiff. They traced the phone number back to a cheap motel in the desert town of Bullhead City, Arizona, and visited the room in question. Inside was the culprit: 77-year-old Steven Martis, a Vietnam veteran with no family who rode a mobility scooter and had a taste for alcohol, weed and Fox News, according to court records.

The agents let him off with a warning.

But as with Robertson in Utah and Smith in Montana, Martis seemed unfazed by the admonishment. Five weeks later, he was at it again, this time targeting then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

In mid-January of 2021 – 11 days after the Capitol riot – Martis left Pelosi another venomous message:

This time, Martis was arrested; investigators found no firearms in his room (though they found a gun part). He was tried and convicted for issuing threats to public officials, and sentenced to 21 months in prison, despite how his probation report – highlighted in court by his attorney – said Martis did not appear to have the means or intent to carry out his criminal threats.

Many threat offenders, however, do have the means – and the apparent propensity – to carry out acts of violence.

A potentially ‘explosive engagement’

CNN discovered 60 cases in which threat-makers had firearms confiscated, and at least 44 cases in which people who made threats took additional steps to follow through.

The most chilling examples were often people who made threats not directly to the public official in their crosshairs, but indirectly to a friend or family member, who then turned them in to authorities. CNN found at least four such offenders who had gone so far as to drive towards Washington, DC, with weapons in their cars.

Among them was Kenelm Shirk III, then a troubled 71-year-old lawyer from a small town in Pennsylvania. On January 21, 2021 – a day after Biden’s inauguration – Shirk became unglued.

That evening, during a fight with his ex-wife – with whom he was living – Shirk said he planned to kill Democratic senators and left in his car. The woman called the police, who tracked him down at a gas station 90 miles away. Inside his car was an assault rifle, two handguns and hundreds of rounds of ammo.

Shirk was brought in for a mental-health evaluation; a nurse told the court that he relayed his plans to her.

Shirk pleaded guilty to making threats to murder Democratic members of the US Senate and was sentenced to time served of 16 months in prison.

Although Shirk’s apparent plan never came to fruition, his case highlights findings by Gary LaFree, a criminology professor from the University of Maryland, who has tracked perpetrators of political violence and their co-conspirators.

These offenders are, on the whole, better educated, older and more financially secure than people who commit other violent crimes, said LaFree, who works with a database that includes attacks on civilians but does not track threats. (LaFree said the average age of perpetrators in his database is 33. Most violent criminals tend to be in their mid-to-late 20s, according to FBI data.)

“They’re not the bottom of the food chain, like the poorest of the poor; they’re more like people who are underachievers,” he said, noting that while socioeconomic status is a good indicator of crime, it’s not as reliable for predicting political violence.

Outright acts of physical violence against public officials have been rare in recent years. And culprits in those cases do not always make threats prior to lashing out physically.

For instance, neither the right-wing conspiracy monger who attacked Paul Pelosi, the husband of former House Speaker Pelosi, with a hammer last fall nor the left-wing extremist who in 2017 opened fire on a group of Republican lawmakers practicing for a charity baseball game in DC – severely wounding current House Majority Leader Steve Scalise and injuring several others – made explicit threats to public officials prior to those attacks, according to the Secret Service and other authorities.

Keneally of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue – a think tank that specializes in researching hate, extremism and disinformation – said while people who commit political violence sometimes make threats beforehand, the more egregious attackers – such as mass shooters – often do not.

“They’re not issuing threats to anyone because they are very much focused on wanting to stay under the radar,” she said.

However, some who make threats do go on to commit heinous acts of violence. A case in point is Robert Card, a 40-year-old National Guard reservist who murdered 18 people in two successive shooting rampages in Maine before dying of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot.

Earlier this fall, Card allegedly accused fellow reservists of calling him a pedophile and threatened to shoot up a drill center at the National Guard facility in Saco, Maine, according to prior reporting from CNN. His threats prompted the Maine National Guard to ask local police to conduct a wellness check on Card, about six weeks before the massacre. Officers were unable to make contact with Card.

Related article: Cops were sent to Maine gunman’s home weeks before massacres amid concern he ‘is going to snap and commit a mass shooting’

But threats don’t need to lead to violence to cause damage – especially when they come in torrents.

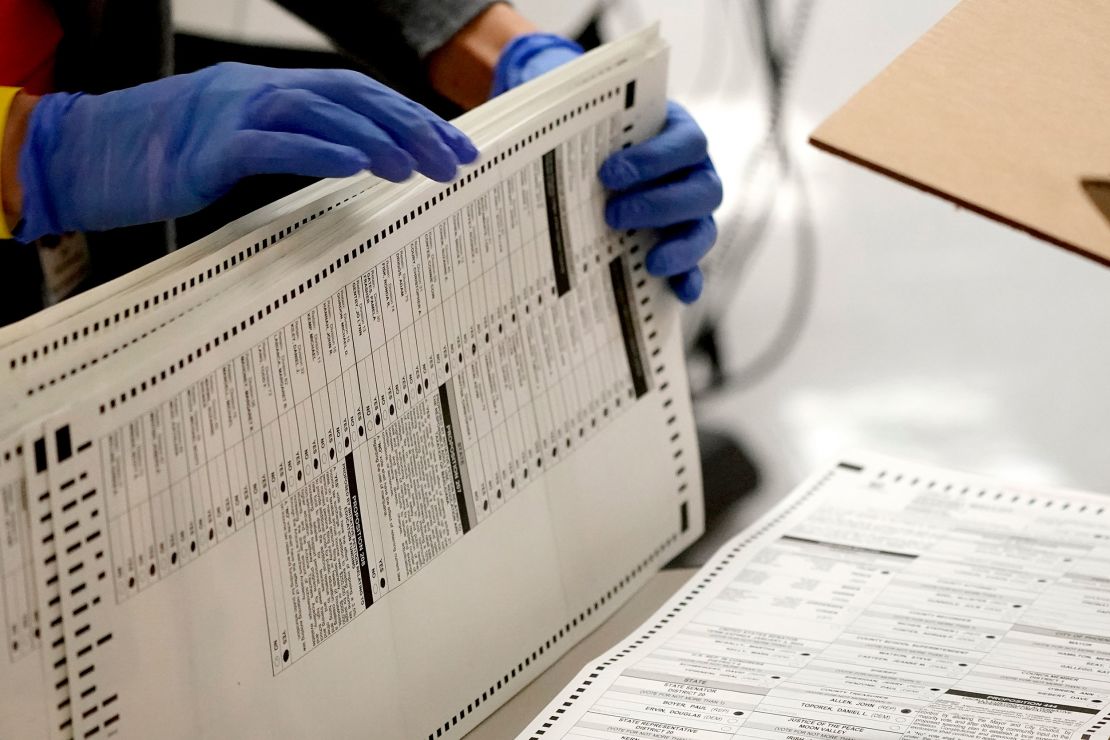

Last year, one in five election workers signaled a desire to walk off the job, with more than half of the workers citing safety concerns after false claims of widespread election fraud in 2020 set off a tidal wave of threats.

“Just because nobody’s killed – bombs not detonated or triggers not pulled – you don’t need those things to happen to still have a really negative impact on our system,” said Pete Simi, a sociologist and associate professor at Chapman University who coauthored the University of Nebraska study.

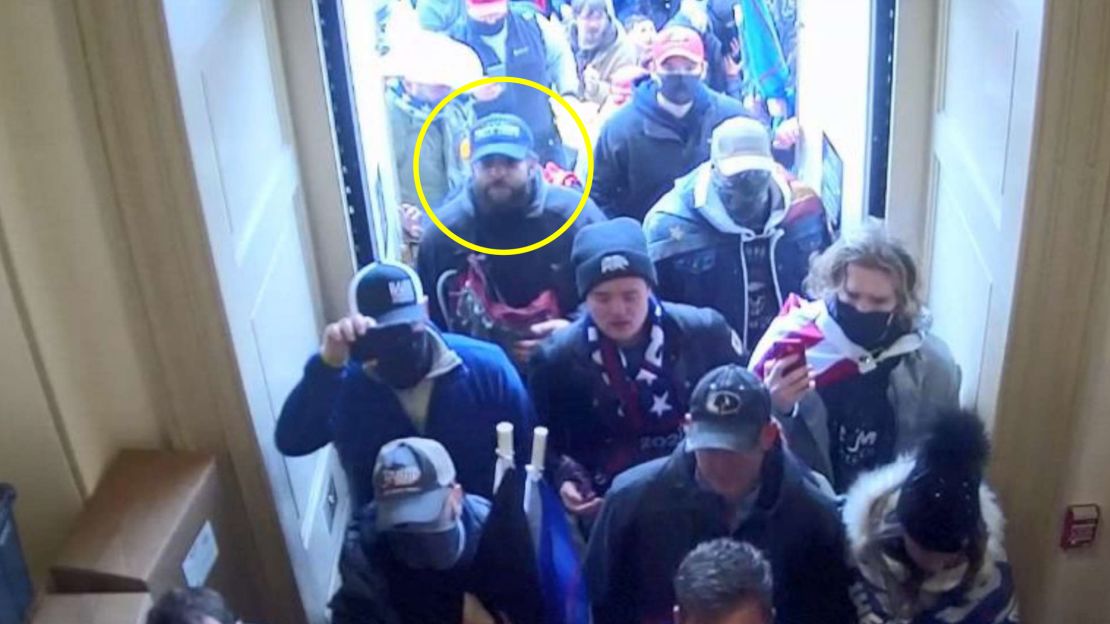

Notably, the 542 prosecuted threats examined by CNN include few cases involving people who showed up at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, for an immense pro-Trump gathering that culminated in a deadly riot. That’s because the vast majority of the 1,200-plus defendants in those cases were charged not for making threats but for other offenses including disorderly conduct, unlawful entry, assault and seditious conspiracy.

However, CNN found a pronounced spike in threat cases in the leadup to and the immediate aftermath of the January 6 attack, underscoring the mass hysteria that made the period so dangerous and destabilizing.

After a firestorm of threats in Arizona, prosecutions are prioritized

Few places were as impacted by this phenomenon as Arizona, which became a hotbed of stolen-election conspiracy theories and threats after the 2020 election.

The onslaught was so bad it led to an exodus of election workers, with two-thirds of the state’s counties losing key personnel due in part to the threats made on their lives and families, according to state Attorney General Kris Mayes.

“I’m very worried,” said Clint Hickman, a member of the local board of supervisors in Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix. “We’re losing an incredible wealth of knowledge.”

As a result, Mayes – who took office in January – says prosecuting threats to election officials is her top priority.

“We’re going to put a stop to that,” she told CNN. “If you do this, you’re going to land in jail.”

This summer, one such perpetrator was handed a stiff sentence for making threats against two Arizona election officials in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

Mark Rissi, then a 63-year-old resident of Iowa, first targeted Hickman, a member of the Maricopa County board that certified the election amid a high-profile right-wing effort to conduct an “audit” of the results.

On September 27, 2021 – less than a week after a private firm conducting the highly controversial “audit” released a draft report affirming Biden’s win – Rissi phoned Hickman’s office from five states away and left a voicemail.

He made a similar call to then-Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, another Republican who’d vouched for the election’s validity.

Rissi’s case illustrates not only how threats to public officials can undermine democracy, but also how the radicalization fueling the threats can tear at the fabric of a family.

Rissi’s son told CNN that his father’s longtime partiality to conspiracy theories went into overdrive a couple of years prior to Trump’s presidency and only picked up steam after Trump took office.

He said his father once bet him $100 that both former President Obama and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would be hung within 30 days.

“How out of touch with reality do you have to be to actually believe that something like that is going to happen?” he said.

(Rissi, who pleaded guilty to two counts of sending a threatening interstate communication, declined to comment for this story.)

Rissi also fumed about the demonstrations over the 2020 police murder of George Floyd – and how his son had participated in one. Late one night, the father left his son a vicious voicemail.

When Rissi took the stand at his sentencing hearing this summer for his threats against Hickman, he struck a contrite tone and pleaded for mercy, claiming he was so heavily medicated with morphine due to chronic back and knee issues that he couldn’t fully remember what he’d said until the FBI played the voicemail back to him at his home.

“When I finally heard the recording that I left for Mr. Hickman, I was horrified,” Rissi said, according to a transcript of his sentencing hearing.

For his part, Hickman, 58, testified that day about the “nightmare” of enduring a bombardment of threats from many culprits in addition to Rissi.

The judge sentenced Rissi to two-and-a-half years in prison, exceeding by six months what the prosecution was seeking.

While Hickman had implored the judge to show “compassion” when sentencing Rissi, he told CNN he is satisfied with the decision.

“Maybe these judges are understanding the threat to our democracy, and they are going to mete out justice,” he said.

To date, the Justice Department, which created a special unit following the 2020 election to prosecute threats of violence against election workers, has filed charges against 20 defendants, Keller said. That includes Rissi, who reports to prison in January.

“The department takes this conduct extremely seriously,” Keller said. “Without those election workers, our elections don’t work. And without our elections, our democracy doesn’t work.”

‘Nothing can stop what’s coming

It’s too soon to know whether the 2024 election will trigger another tsunami of threats.

While there has been no shortage of alarming incidents of late, CNN’s analysis found that threats that led to federal prosecutions actually plunged from a peak of 72 in 2021 to 46 last year. Politically motivated ones also fell in that timeframe from 38 to 20.

Also declining last year was the overall number of threats and concerning statements to public officials in at least two big categories.

Such messages targeting members of Congress dropped 22% in one year, to 7,500, in 2022 – though that tally is still nearly twice as high as it was in 2017, when the Capitol Police started releasing the figures. Manger told CNN his agency has already investigated 7,300 threat assessment cases this year and is on track to top 8,000.

Threats and “inappropriate communications” to judges and other courtroom personnel plummeted 70% in 2022, to 1,362 – the lowest level since 2015, according to the US Marshals Service.

Looking ahead, the federal government has begun to weigh in on what to expect in 2024.

The Department of Homeland Security released a threat assessment for next year saying it anticipates the threat of violence committed by people radicalized in the US – mostly “lone offenders” – to remain “high, but largely unchanged.”

Manger told CNN that his agents are inundated with threat assessment cases, each handling roughly 500 a year. It amounts to a “grueling” workload for the resource-strapped agency as it prepares for a potential spike in threats to federal lawmakers in 2024.

“There’s so much hate, vitriol, you know, just hate speech that goes on on social media and elected officials,” he said. “I’m not just talking about here at the Capitol; I’m talking about elected officials all over the country are just targets now more so than I think they ever were.”

Regardless of the current trendline, state and federal officials have responded in recent months to a steady drumbeat of unsettling incidents.

In May, a 60-year-old right-wing conspiracy theorist left a voicemail in the office of a Texas Congresswoman calling her a “tranny and a pedophile” and threatening to “put a bullet” in her face; the suspect, Michael David Fox, pleaded guilty to making a threat. In late September, another Montana man – this one a 29-year-old whose history of menacing behavior had previously led to the confiscation of his five firearms – was accused of making death threats to Sen. Tester; he agreed to plead guilty. Last month, the offices of two Georgia Republicans in Congress – Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Rich McCormick – received death threats; McCormick temporarily closed a Georgia office as a result.

All the while, the approaching election and Trump indictments have already proved a combustible cocktail on Trump’s social media platform, Truth Social, with Trump himself posting scores of rants, ranging from the vengeful to the dangerous.

On June 29, the former president posted what he said was Obama’s home address on the platform. Trump’s message was re-posted that same day on Truth Social by 37-year-old Taylor Taranto, who then posted a comment on Telegram saying “See you in hell, Podesta’s and Obama’s” before driving to the area and live-streaming himself on YouTube walking around Obama’s DC neighborhood. Taranto – who sometimes bragged to his listeners that he stormed the Capitol on January 6 – was arrested by Secret Service agents after a brief pursuit on foot in a wooded area near the neighborhood. They seized from his van two handguns, hundreds of rounds of ammunition and a machete.

Taranto is currently being held at a Philadelphia jail, awaiting trial on charges stemming from the Capitol riot and the June 29 incident. His attorney did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

The day before he showed up in Obama’s neighborhood, Taranto had livestreamed from his van that he was in Maryland and wanted to blow up the National Institute of Standards and Technology. His ramblings included an ominous message for then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, whose office had recently spurned Taranto’s request for surveillance footage of the January 6 attack.

“Coming at you McCarthy,” Taranto said. “Can’t stop what’s coming. Nothing can stop what’s coming.”

HOW WE REPORTED THIS STORY

To track the rise of politically motivated threats over the last decade, CNN reviewed thousands of pages of court documents, press releases and other records.

CNN assembled a list of federal criminal cases filed between January 2013 and November 2023 in which defendants were accused of threatening public officials or institutions. Reporters combined data from the National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology and Education Center (NCITE), The Prosecution Project, press releases from the Offices of the United States Attorneys and information provided by the Department of Justice Election Threats Task Force.

In August, NCITE, located at the University of Nebraska, released a report on threats against public officials based on cases it identified through press releases from US Attorney offices and news reports. NCITE shared the list of defendants it found with CNN shortly after their report came out.

CNN then searched The Prosecution Project’s public database – which tracks felony criminal cases involving political violence since 1990 – for additional cases that fit the parameters of this story. The Prosecution Project is an open-source research platform and identifies its cases through court records, news reports and government press releases.

CNN added several more cases filed in recent months by searching press releases from United States Attorney offices. Finally, the Department of Justice Election Threats Task Force provided CNN with a list of additional cases involving threats against election officials in which charges were brought.

Reporters excluded duplicates and analyzed more than 540 cases by reading press releases, court records and news reports to identify the trends and statistics laid out in this story.

To avoid capturing prosecution lags in the timeline analysis, CNN used court records or government statements to determine the date the threat was made. If multiple threats were communicated over time, CNN used the earliest date available.

CNN defined politically motivated threats as those targeting named elected officials or election employees or threats focusing on hot-button political issues like abortion rights, police brutality or gun control. Threats that stemmed from a perceived personal grievance – for example, an inmate who threatened the prosecutor of his case and also targeted an elected official in his message – were not considered politically motivated.

Because the party affiliation of political appointees is not always clear, CNN included the affiliation of the administration that appointed them.

Federal charges were filed in all the cases included in CNN’s analysis, but the disposition of each case is not known; some are still ongoing, and others may have been dismissed or acquitted. NCITE found that nearly 80% of prosecuted threats it examined ended in convictions. CNN has not included cases filed in state courts.

CLARIFICATION: This story has been updated to reflect that the Georgia state attorney general’s office was referring to cases that were submitted to and reviewed by the office when it confirmed that none of the threats to election officials in the state warranted filing charges. Those cases, a spokesperson said, didn’t include the “served lead” voicemail that Richard Barron noted.