At the foot of a dune in a nameless corner of the Sahara Desert, a woman falls to the ground. Ahead, a caravan of wandering souls snakes away. She calls for help and a young man – a boy, really, aged by what he’s seen and done – peels off, racing to her aid. He lifts her up and over his head until she’s flying, the hem of her dress fluttering like a mermaid’s tail despite the still air. Holding hands, they journey on together.

Except that was all a fantasy. He did not stop. The woman likely died where she fell, soon to join the remains of other African migrants who have slipped beneath the sand, never to make it to Europe.

In “Io Capitano” (“Me Captain”) by director Matteo Garrone, there is no shame in retreating into imagination. It offers comfort when life can’t, and there’s much hardship to endure. A migrant drama told from the perspective of two Senegalese cousins who journey across West Africa to Italy, the film is an odyssey with touches of “The Odyssey,” alive to the spectacle of their undertaking.

What starts as an adventure for Seydou and Moussa, played by first-time actors Seydou Sarr and Moustapha Fall, descends into extortion, exploitation and death as they make their way north through Niger and Libya to the fringes of the Mediterranean. (The title refers to migrants coerced into becoming captains of vessels crossing the sea.)

“Io Capitano” premiered last week at the Venice Film Festival, where Garrone won the award for best director and Sarr was named best young actor, and was released in Italian cinemas on September 7. It arrives as hostility towards migrants brews in the nation’s politics. Cutting through the chilling statistics – over 2,700 migrants are listed as dead or missing in the Mediterranean already this year – Garrone tells a deeply empathetic story, following it back to its source.

“I wanted to portray a phenomenon that we are all convinced that we know under a different light, in order to show people that it’s not only a matter of boats coming ashore,” Garrone told CNN in a phone call from Venice.

“My approach was to try and make a sort of reverse shot,” he added. “To completely turn that perspective that we (Europeans) are used to seeing, and place my camera from Africa to Europe, so the gaze is the opposite.”

African cinema is no stranger to stories of migration to Europe. Some of its most vital films engage with the subject, including “Black Girl” (1966) by Ousamane Sembène and “Soleil Ô” (1970) by Med Hondo, from Senegal and Mauritania respectively. They, like many films made by African and European filmmakers, examine the new lives of Africans in Europe. There have been other approaches; recent Cannes winner “Atlantics” (2019) by French Senegalese director Mati Diop pulled focus on the friends and family left behind, making a ghost story of migration. But for a White European director like Garrone to root a migrant story in Africa is unusual.

To do so, he turned to Mamadou Kouassi, an Ivorian who undertook the journey with his cousin some 15 years ago. Kouassi now lives in Caserta near Naples, Italy, and is a cultural mediator between authorities and new migrants, helping them to share their stories. Acting as a script consultant, Kouassi described what happened to him in a series of meetings with Garrone and his co-writers; much of it made it into the film.

“Mamadou’s story was most precious to me, because his account revealed aspects that really surprised me and that I had totally ignored,” said the director. “Those are the very human, intimate details that are at the base of the choice to leave their country.”

“This is telling a story that most films are not telling, because most of the time they’re not starting from the beginning,” said Kouassi. In the film, the boys visit a Marabout, a spiritual leader, to psychologically prepare them, and who tells them to seek permission from their dead ancestors to leave – steps Kouassi took. These cultural references take on greater significance as the film progresses and become one of its greatest storytelling assets.

Seydou Sarr and Moustapha Fall were cast from around 100 hopefuls. “When we met, something clicked between us,” Sarr recalled, “(Fall) was immediately my friend. From there we shared the same experiences, sharing the same room for the shoot. This strengthened (our bond) even more.”

Principal photography took place in Senegal, Morocco and Italy, and was an eye-opening experience for the actors. “It really changed me and my way of looking at the sacrifices and suffering of migrants,” said Fall, highlighting the scenes in the Sahara (filmed in Morocco) as the most challenging to shoot.

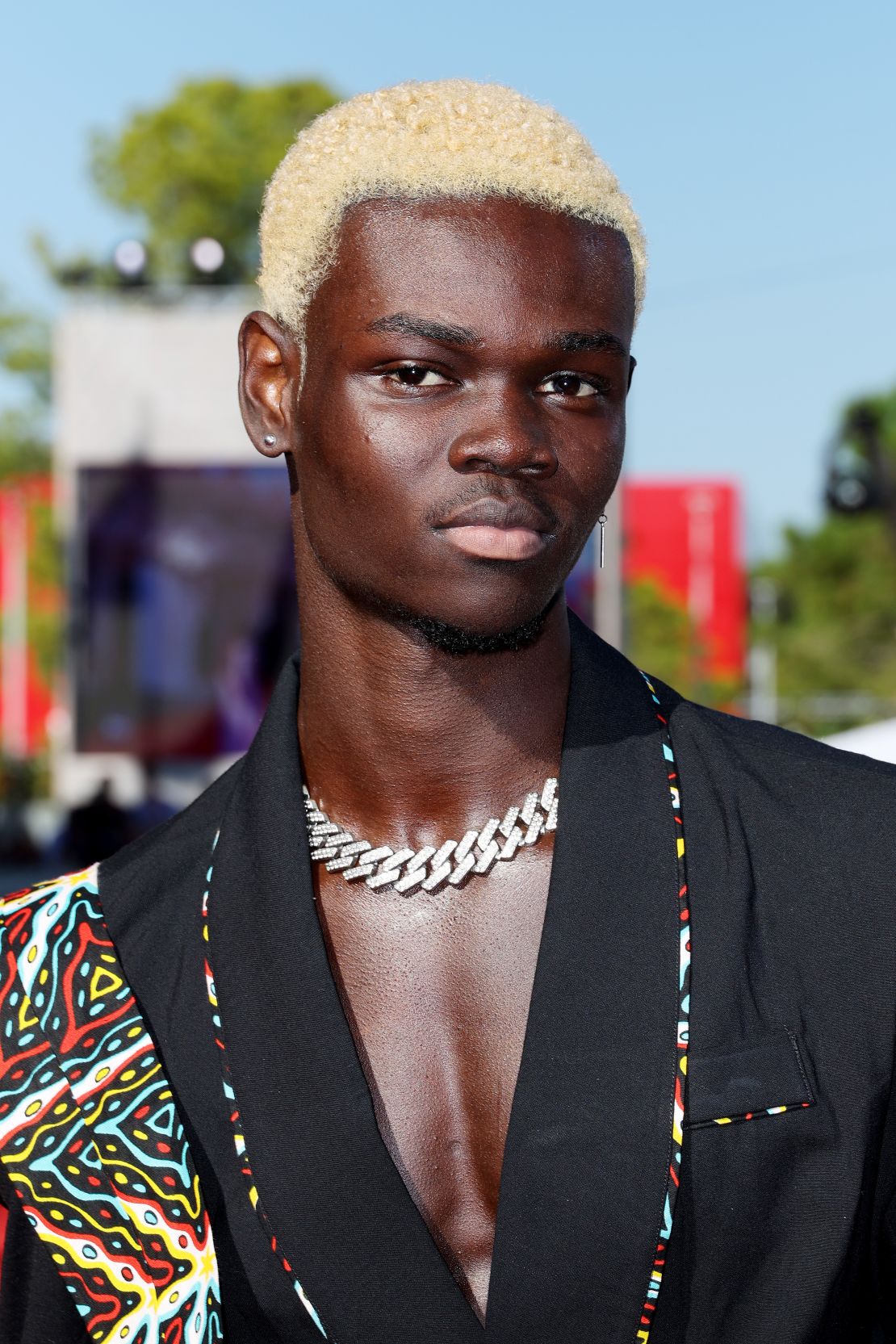

Both said they’d like to continue acting, with Fall adding he’d like to pursue modeling too (if his appearance on the Venice red carpet is anything to go by, he might be on to something).

Full of aspiration, they share some of the same traits as their fictional namesakes. Sarr is a TikTok star in Senegal whose passion for singing was incorporated into the script; his character left Senegal with hopes of becoming a recording artist in Europe.

“Io Capitano” depicts Europe as equal parts place and idea – an idea mediated by what the boys have seen and heard through smartphone screens; close enough to hold in the palm of one’s hand yet frustratingly inaccessible. “Europe is nothing like you imagine,” they are warned, but Seydou and Moussa see it as the only place to realize their dreams.

“Young Africans are exposed as much as we are to globalization, which means that they have a constant window open on them to the lifestyle of the Western world,” said Garrone. “They share a very human desire to improve their living conditions and try their luck in the West.”

“They see their peers – European kids – come on holiday to Africa, completely free and flying in with no concerns,” he continued, adding that young Africans want the same freedom of travel.

Like Seydou in “Io Capitano,” Kouassi said he witnessed people abandoned in the desert, was separated from his cousin and later detained in Libya – fictionalized in graphic and distressing detail by Garrone. “I started crying during the film,” Kouassi said, speaking the day after the premiere. “This movie makes me re-experience my life 15 years ago. It is an emotion I had forgotten.”

He is nevertheless grateful to the director for his approach: “Matteo did not leave anything (out). He explained – he exposed – the reality and the truth.”

“Io Capitano” ends on an ambiguous note. It also ends where another film might begin, though Garrone has yet to commit to a follow up.

The director hopes the movie will be shown in European and African schools as a reminder of European privileges and a lesson in the dangers faced by West African migrants. Kouassi agrees, adding older audiences should also be taking note.

“This is exposing how we have been cut off from human rights,” he said. “I think it is important – it is sending a very great message to Europe.”

“Io Capitano” premiered at the Venice Film Festival on September 6. A release date in the US and UK is yet to be announced.