“Knowledge is power,” says Samantha Carlucci, 26. The Ravena, New York, resident recently had a hysterectomy that included removing her fallopian tubes – and believes it saved her life.

The Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance is drawing attention to the role of fallopian tubes in many cases of ovarian cancer and now says more women, including those with average risk, should consider having their tubes removed to cut their cancer risk.

About 20,000 women in the US were diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022, according to the National Cancer Institute, and nearly 13,000 died.

Experts have not discovered a reliable screening test to detect the early stages of ovarian cancer, leading them to rely on symptom awareness to diagnose patients, according to OCRA.

Unfortunately, symptoms of ovarian cancer often don’t present themselves until the cancer has advanced, causing the disease to go undetected and undiagnosed until it’s progressed to a later stage.

“If we had a test to detect ovarian cancer at early stages, the outcome of patients would be significantly better,” said Dr. Oliver Dorigo, director of the division of gynecologic oncology in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Stanford University Medical Center.

Until such a test is widely available, some researchers and advocates suggest a different way to reduce the risk: opportunistic salpingectomy, the surgical removal of both fallopian tubes.

Research has found that nearly 70% of ovarian cancer begins in the fallopian tubes, according to the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance.

Doctors have already been advising more high-risk women to have a salpingectomy. Several factors can raise risk, including genetic mutations, endometriosis or a family history of ovarian or breast cancer, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

If they accept that they won’t be able to get pregnant afterward and if they are already planning on having pelvic surgery, it can be “opportunistic.”

“We are really talking about instances where a surgeon would already be in the abdomen anyway,” such as during a hysterectomy, said Dr. Karen Lu, professor and chair of the Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Although OCRA shifted its recommendation to include women with even an average risk of ovarian cancer, some experts continue to emphasize fallopian tube removal only for women with a high risk. Some are calling for more research on the procedure’s efficacy in women with an average risk.

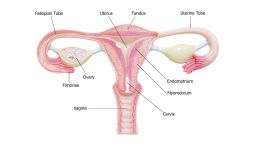

Fallopian tubes are generally 4 to 5 inches long and about half an inch thick, according to Dorigo. During an opportunistic salpingectomy, both tubes are separated from the uterus and from a thin layer of tissue that extends along them from the uterus to the ovary.

The procedure can be done laparoscopically, with a thin instrument and a small incision, or through an open surgery, which involves a large incision across the abdomen.

The procedure adds roughly 15 minutes to any pelvic surgery, Dorigo said.

Unlike a total hysterectomy, in which a woman’s uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed, the removal of the tubes themselves does not affect the menstrual cycle and does not initiate menopause.

The risks associated with an opportunistic salpingectomy are also relatively low.

“Any surgery carries risk … so you do not want to enter any surgery without being thoughtful,” Lu said. “The risk of a salpingectomy to someone that is already undergoing surgery, though, I would say is minimal.”

‘It can bring so much relief’

Many women who have had the procedure say the benefit far outweighs the risk.

Carlucci had her fallopian tubes removed in January during a total hysterectomy, after testing positive for a genetic condition called Lynch syndrome that multiplied her risk of many kinds of cancers, including in the ovaries.

Several members of her family have died of colon and ovarian cancer, she said, and it prompted her to look into the available options.

Knowing that she could choose an opportunistic salpingectomy, which greatly decreased her chances of ovarian cancer, gave her hope.

As part of the total hysterectomy, it eliminated her risk of ovarian cancer.

“You can’t change your DNA, and no amount of dieting and exercise or medication is going to change it, and I felt horrible,” Carlucci said. “When I was given the news that this would 100% prevent me from ever having to deal with any ovarian cancer in my body, it was good to hear.”

Carlucci urges any woman with an average to high risk of ovarian cancer to talk to their doctor about the procedure.

“I know it seems scary, but this is something that you should do, or at the very least consider it,” she said. “It can bring so much relief knowing that you made a choice to keep you here for as long as possible.”

Monica Monfre Scantlebury, 45, of St. Paul, Minnesota, had a salpingectomy in March 2021 after witnessing a death related to breast and ovarian cancer in her family.

In 2018, Scantlebury’s sister was diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer at 27 years old.

“She went on to fight breast cancer,” Scantlebury said. “During the beginning of the pandemic, in March of 2020, she actually lost her battle to breast cancer at 29.”

During this period, Scantlebury herself found out that she was positive for BRCA1, a gene mutation that increases a person’s risk of breast cancer by 45% to 85% and the risk of ovarian cancer by 39% to 46%.

After meeting with her doctor and discussing her options, she decided to have a salpingectomy.

Her doctor told her she would remove the fallopian tubes and anything else of concern that she found during the procedure.

“When I woke up from surgery, she said there was something in my left ovary and that she had removed my left ovary and my fallopian tubes,” Scantlebury said.

Her doctor called about a week later and said there had been cancer cells in her left fallopian tube.

The salpingectomy had saved her life, the doctor said.

“We don’t have an easy way to be diagnosed until it is almost too late,” said Scantlebury, who went on to have a full hysterectomy. “This really saved my life and potentially has given me decades back that I might not have had.”

‘Look at your family history’

Audra Moran, president and CEO of the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, is sending one message to women: Know your risk.

Moran believes that if more women had the power of knowing their risk of ovarian cancer, more lives would be saved.

“Look at your family history. Have you had a history of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, colorectal or uterine in your family? Either side, male or female, father or mother?” Moran said. “If the answer is yes, then I would recommend talking to a doctor or talking to a genetic counselor.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

The alliance offers genetic testing resources on its website. A genetic counselor assess people’s risks for varying cancers based on inherited conditions, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Carlucci and Scantlebury agree that understanding risk is key to preventing deaths among women.

“It’s my story. It’s her story. It’s my sister’s story … It is for all women,” Scantlebury said.