Editor’s Note: CNN Films’ “American Pain” premieres Sunday, February 5, at 9 p.m. ET/PT on CNN.

Throngs of people hang outside the American Pain clinic in Boca Raton, Florida, waiting their turn. Inside, a doctor greets them one by one and prescribes them pain medication, a handgun peeking out from under his white coat.

American Pain is a one-stop shop, supplying both prescriptions and painkillers. At the door, a hulking bouncer warns people not to snort their pills in the parking lot. That would attract the kind of attention that the clinic’s owners, twin brothers Chris and Jeff George, are trying to avoid.

But it’s too late. Local and federal investigators are nearby, watching every move.

These are scenes from a new CNN Films’ documentary, “American Pain,” which details the George brothers’ rise and fall as opioid kingpins. The film by Emmy Award-winning director Darren Foster uses FBI wiretap recordings and undercover videos – along with the brothers’ exclusive jailhouse interviews – to paint a picture of a ruthless pain-pill empire that turned the Georges into millionaires and enabled addicts from all over the country.

“The George brothers did not start the opioid crisis. But they sure as hell poured gasoline on the fire,” said retired FBI agent Kurt McKenzie, who was part of the investigation – nicknamed Operation Oxy Alley – that began after oxycodone from the twin brothers’ clinics showed up at scenes involving drug overdoses. Investigators bugged the clinic’s phones, recorded surreptitious video and sent undercover agents masquerading as a patients to buy drugs.

“They became the largest street-level distribution group operating in the entire United States,” McKenzie added. “Nobody put more pills on the streets than they did. Nobody … and they were operating in broad daylight.”

One brother described their operation as ‘the Disneyland of pain clinics’

Between them, Chris and Jeff George ran four pain clinics and other related businesses in South Florida.

Their operation coincided with surge in the opioid epidemic between 2008 and 2010, when the prescription painkiller business was booming, federal officials said. People across the country also were beginning to realize the toxic toll the legal drugs were taking on communities.

“Before this case, the public only knew that people were dying from drug overdoses, they had no idea how the ‘system’ worked,” McKenzie said. “The George brothers created the blueprint.”

They advertised the clinic in local newspapers and recruited doctors to prescribe the medications, offering them incentives for large and frequent prescriptions. To avoid setting off red flags, the brothers’ clinics only accepted cash and credit cards – not insurance plans, according to court documents. They hired women through Craigslist to dole out the pills prescribed by the doctors.

The George brothers made it easy to get drugs at their clinics, where no appointments were necessary. Patients flocked to Florida from Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia and other Appalachian states ravaged by opioid abuse.

“I believe we’ve created a new form of tourism,” Jeff George says in the documentary, in a phone interview from prison. “We were basically like the Disneyland of pain clinics.”

Some drug dealers drove to the clinics from Kentucky in rented buses marked “Tree of Life Baptist Church” to mask their criminal intentions, the film shows.

“It’s like a candy store down there,” one man told FBI agent Jennifer Turner, who led the federal investigation, when asked why he frequented the George brothers’ pill mills.

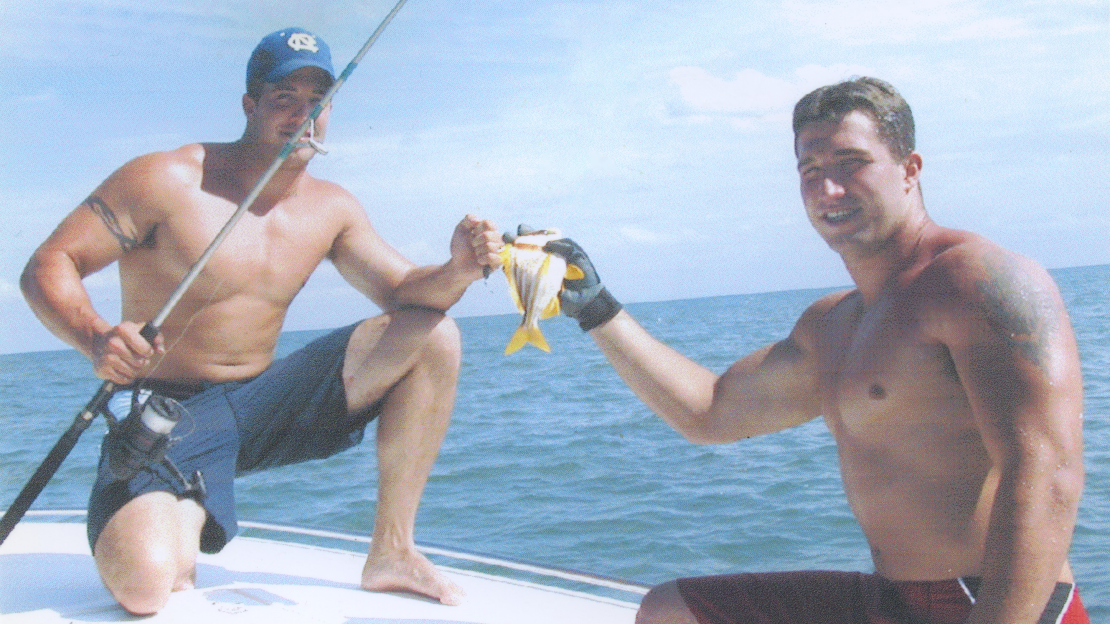

Meanwhile, the brothers were making millions and trying to outdo each other’s flamboyant lifestyles. They bought pricey watches, flashy cars, boats and multiple homes. Jeff George drove a Lamborghini while his brother Chris had an enormous customized monster truck.

The clinics operated like frat houses, said Derik Nolan, a longtime friend of the twins who describes himself in the documentary as their right-hand man. As customers waited for their next fix, clinic employees played with remote-controlled cars and shot each other with slingshots. The clinics’ fridges held beer and Patrón shots, Nolan said.

The clinics’ cash registers were too small to contain the incoming flood of bills, so employees stuffed the money in massive trash bags.

They bragged about making millions of dollars in profits

One clinic referred people without MRIs to a trailer behind a strip club, where they could get lap dances while waiting for new scans from sham radiologists, according to an FBI agent quoted in the film. The George brothers believed the imaging helped make their prescription process look more genuine.

The clinics’ doctors were paid per person, which provided an incentive to see as many patients as possible, federal officials said.

The doctors “did not obtain prior medical records or prescribe any alternative treatment. They did not make referrals to specialists. Virtually everyone examined by the co-conspirator physicians received a prescription for controlled substances,” court documents said. “There was no individualization of treatment as required under applicable federal and Florida law.”

Chris George brags in the film that the American Pain clinic alone generated $40 million in profits. American Pain prescribed 18 million units of oxycodone, ranking among the top nine purchasers of oxycodone in the nation, according to court documents.

“Of the 20 highest-prescribing physicians in the entire country, five of them worked at just one of Chris’ facilities,” said McKenzie, the former FBI agent. “These are real doctors. They have real licenses … and what looked to be a real clinic.”

Chris George says he took pride in his clinics’ volume.

“I wanted my doctors to be the top prescribing doctors in the country,” he tells the filmmakers in an interview from prison. “To me, that was an accomplishment.”

A grieving father helped bring down a pill mill

John Friskey owns a computer service business in Jacksonville, Florida. At the time a pill mill moved in to the same strip mall, Friskey was a grieving father who’d lost his son, Andy, to opioid addiction. Andy loved music and played the guitar.

“He was in a car accident in Tennessee. He had a ruptured spleen and was in pain,” Friskey told CNN. “He got medicine from the pill mills. I didn’t know they were pill mills. I didn’t even know he was getting medicine. He overdosed on it.”

The neighboring pain clinic was owned by a man named Zachary Rose, who was rivaling the George brothers for supremacy among Florida pill mills. Rose’s clinic brought crowds of drug users from out of state to the area, and Friskey wanted him out of the strip mall.

When the clinic asked Friskey to help them maintain their computer networks and security cameras, Friskey saw an opportunity. He approached the DEA and offered to help shut it down.

DEA agents wired him and recorded his conversations when he worked on Rose’s computers, as doctors there bragged about how much money they earned per day.

Friskey said he would take out their hard drives, replace them with new ones and turn the old ones over to federal agents.

“They never questioned me, never tried to stop me,” Friskey said. “I was happy to shut him down.”

Rose pleaded guilty to a drug conspiracy charge in 2012 and was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

An estimated 3,000 people died from overdoses linked to the brothers’ clinics, the FBI says

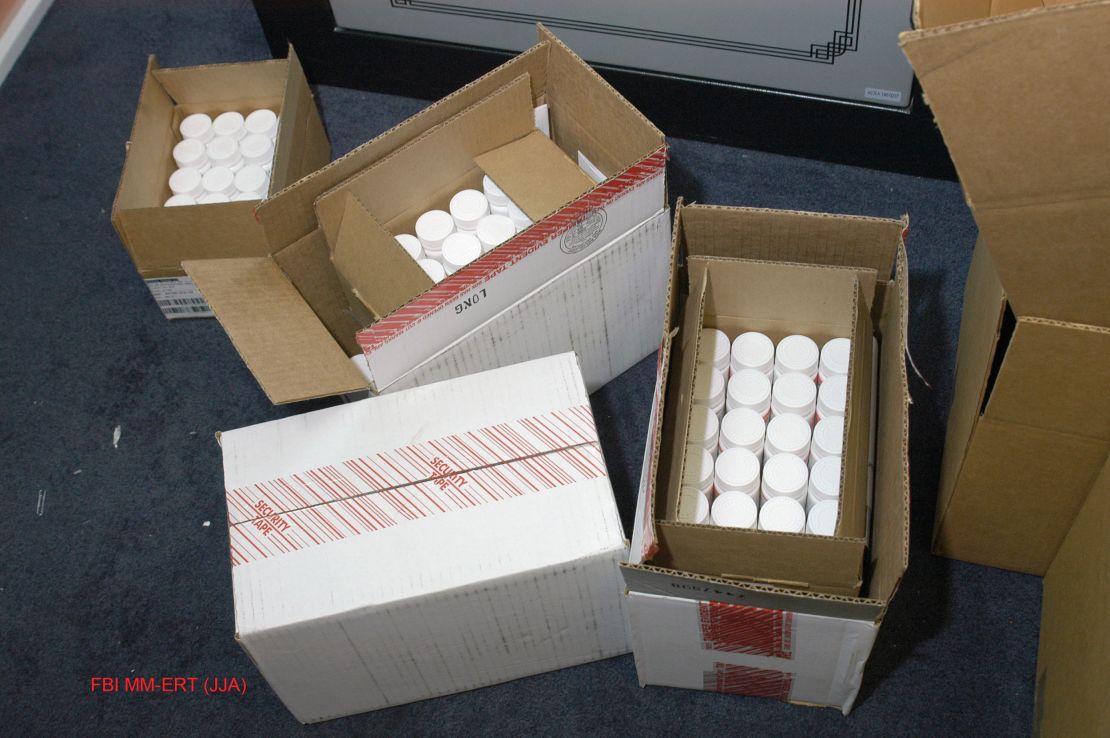

Everything came crashing down in August 2011, when federal investigators raided the brothers’ homes and discovered illegal weapons, drugs and other items.

They also raided the home of the twins’ mother, Denice Haggerty, who worked at one of the pain clinics. There, they discovered safes in the attic stashed with $4 million.

The brothers were among 31 people indicted – including their mother – under the federal RICO Act, which targets organized crime. Thirteen doctors also were charged, and all but two pleaded guilty to lesser charges of money laundering or wire fraud.

Haggerty, the twins’ mother, pleaded guilty that year to one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and was sentenced to 30 months in prison.

Chris George pleaded guilty to one count of racketeering conspiracy and was sentenced to 17 years in prison. He served 11 years and was released in September 2021.

Jeff George also pleaded guilty to a racketeering conspiracy charge and was sentenced to 15 and a half years. He also was convicted of second-degree felony murder in the fatal overdose of a patient, according to court filings. He received an additional 20-year sentence for the murder charge and remains in prison.

An estimated 3,000 people died from overdoses linked to the brothers’ clinics, McKenzie said. He said the FBI came up with that number after reviewing a random sampling of 300 patient files from the brothers’ clinics and noting how many of the patients had later overdosed.

As many of the clinics’ customers sold their pills to others, that estimate doesn’t include the secondary or even tertiary drug market, McKenzie added.

Chris George denied responsibility for clients’ fatal overdoses

The brothers, now 42, leave a legal legacy in Florida.

In 2011, the state passed a “pill mill law” that banned pain clinics from dispensing opioids and established requirements for medical examinations.

But Nolan, the Georges’ associate who also pleaded guilty to a racketeering charge and served 10 years in person, feels like law enforcement targeted the wrong people.

“They didn’t want to go after big pharmacy. They didn’t want to go after big distributors. They just wanted us – we’re nobody. The money we made is peanuts compared to what big pharma made over the years,” he said in the film.

In recent years large pharmaceutical companies such as Purdue Pharma, whose OxyContin painkiller has been widely blamed for kickstarting the opioid crisis, have agreed to pay billions of dollars in legal settlements. Drugstore chains such as CVS and Walgreens also have agreed to settle lawsuits brought by states and local governments alleging the retailers mishandled prescriptions of painkillers.

Meanwhile, more than a decade after the FBI shut down their operation, Chris George believes he and his brother play no role in the fatal overdoses.

“In the end, it’s their responsibility. They’re responsible for themselves, I’m not,” he says in the film after his release from prison. “I don’t think we created more addicts. They were already here. They just had an easier way .. to get their drugs. And a safer way. Now they don’t even know what they’re getting.”

Chris George, who is out on parole, continues to deflect blame for his drugs’ deadly toll onto his former patients.

“They said they were in pain to my doctors. They got an MRI showing they were in pain. My doctors gave them medication. What they did with that is out of my hands.

“They act like I’m the bad guy here ‘cause I owned a business,” he added. “You know, in this country, anybody can open a business.”

Chris George said he plans to start a real estate business with his friend Nolan.

And if the housing market crashes, like it did during their opioid empire’s heyday, Nolan told the makers of “American Pain” that he has another idea.

“We may have to venture back into the medical field,” he said.