Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Some 125,000 years ago, enormous elephants that weighed as much as eight cars each roamed in what’s now northern Europe.

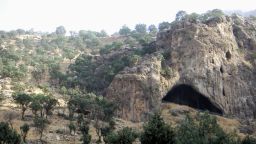

Scientifically known as Palaeoloxodon antiquus, the towering animals were the largest land mammals of the Pleistocene, standing more than 13 feet (4 meters) high. Despite this imposing size, the now-extinct straight-tusked elephants were routinely hunted and systematically butchered for their meat by Neanderthals, according to a new study of the remains of 70 of the animals found at a site in central Germany known as Neumark-Nord, near the city of Halle.

The discovery is shaking up what we know about how the extinct hominins, who existed for more than 300,000 years before disappearing about 40,000 years ago, organized their lives. Neanderthals were extremely skilled hunters, knew how to preserve meat and lived a more settled existence in groups that were larger than many scholars had envisaged, the research has suggested.

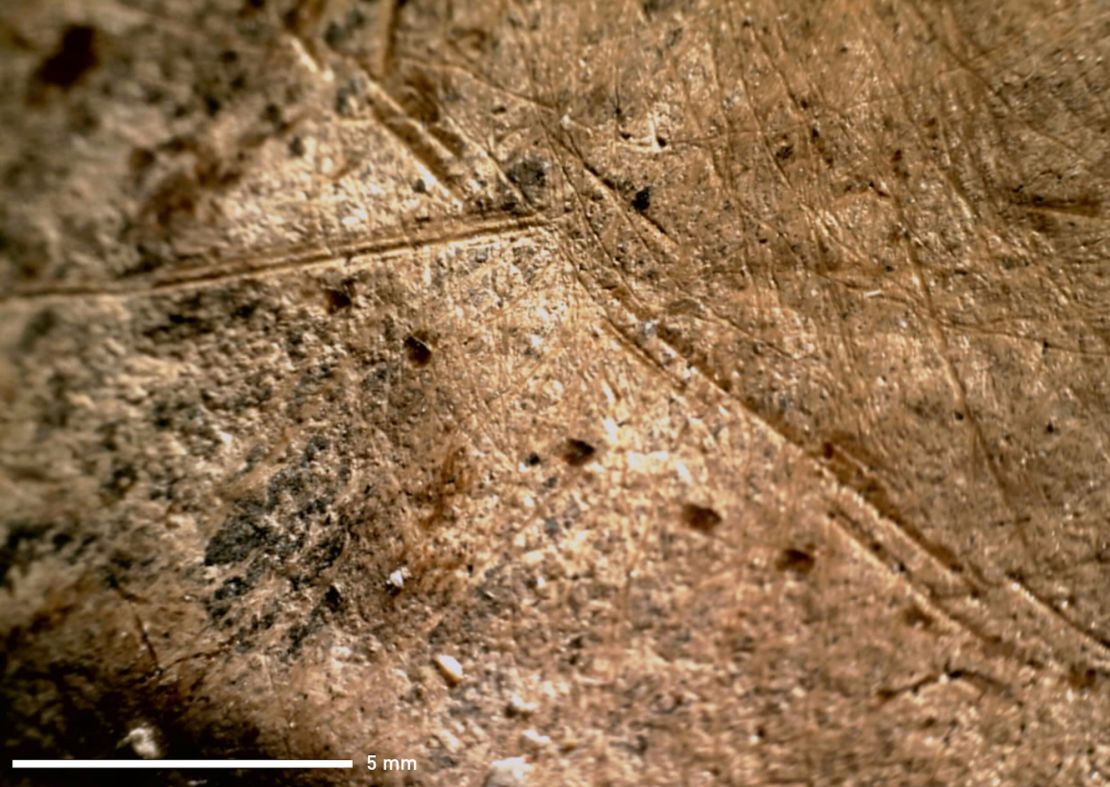

A distinct pattern of repetitive cut marks on the surface of the well-preserved bones — the same position on different animals and on the left and right skeletal parts of an individual animal — revealed that the giant elephants were dismembered for their meat, fat and brains after death, following a more or less standard procedure over a period of about 2,000 years. Given a single adult male animal weighed 13 metric tons (twice as much as an African elephant), the butchering process likely involved a large number of people and took days to complete.

Stone tools have been found in northern Europe with other straight-tusked elephant remains that had some cut marks. However, scientists have never had clarity on whether early humans actively hunted elephants or scavenged meat from those that died of natural causes. The sheer number of elephant bones with the systematic pattern of cut marks put this debate to rest, said the authors of the study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The Neanderthals likely used thrusting and throwing spears, which have been found at another site in Germany, to target male elephants because of their larger size and solitary behavior, said study coauthor Wil Roebroeks, a professor of Paleolithic archaeology at Leiden University in Germany. The demographics of the site skewed toward older and male elephants than would be expected had the animals died naturally, according to the study.

“It’s a matter of immobilizing these animals or driving them into muddy shores so that their weight works against them,” he said. “If you can immobilize one with a few people and corner them into an area where they get stuck. It’s a matter of finishing them off.”

Preparation of big-game meat

What was most startling about the discovery was not that Neanderthals were capable of hunting such large animals but that they knew what to do with the meat, said Britt M. Starkovich, a researcher at the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen in Germany, in commentary published alongside the study.

“The yield is mindboggling: more than 2,500 daily portions of 4,000 calories per portion. A group of 25 foragers could thus eat a straight-tusked elephant for 3 months, 100 foragers could eat for a month, and 350 people could eat for a week,” wrote Starkovich, who was not involved in the research.

“Neanderthals knew what they were doing. They knew which kinds of individuals to hunt, where to find them, and how to execute the attack. Critically, they knew what to expect with a massive butchery effort and an even larger meat return.”

The Neanderthals living there likely knew how to preserve and store meat, perhaps through the use of fire and smoke, Roebroeks said. It’s also possible that such a meat bonanza was an opportunity for temporary gatherings of people from a larger social network, said study coauthor Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser, a professor of prehistoric and protohistoric archaeology at the Johannes Gutenberg-University in Mainz, Germany.

She explained the occasion could perhaps have served as a marriage market. An October 2022 study based on ancient DNA from a small group of Neanderthals living in what’s now Siberia suggested that women married outside their own community, noted Gaudzinski-Windheuser, who is also director of the Monrepos Archaeological Research Centre and Museum of Human Behavioural Evolution in Neuwied.

“We don’t see that in the archaeological record but I think the real benefit of this study is that now everything’s on the table,” she said.

Changing misperceptions

Scientists had long thought that Neanderthals were highly mobile and lived in small groups of 20 or less. However, this latest finding suggested that they may have lived in much bigger groups and been more sedentary at this particular place and time, when food was plentiful and the climate benign. The climate at the time — before the ice sheets advanced at the start of the last ice age around 100,000 to 25,000 years ago — would have been similar to today’s conditions.

Killing a tusked elephant would not have been an everyday event, the study found, with approximately one animal killed every five to six years at this location based on the number found. It’s possible, however, that more elephant remains were destroyed as the site is part of a open cast mine, according to the researchers. Other finds at the site suggested Neanderthals hunted a wide array of animals across a lake landscape populated by wild horses, fallow deer and red deer.

More broadly, the study underscores the fact that Neanderthals weren’t brutish cave dwellers so often depicted in popular culture. In fact, the opposite is true: They were skilled hunters, understood how to process and preserve food, and thrived in a variety of different ecosystems and climates. Neanderthals also made sophisticated tools, yarn and art, and they buried their dead with care.

“To the more recognizably human traits that we know Neanderthals had — taking care of the sick, burying their dead, and occasional symbolic representation — we now also need to consider that they had preservation technologies to store food and were occasionally semi sedentary or that they sometimes operated in groups larger than we ever imagined,” Starkovich said.