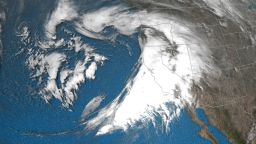

For three years, California has been in desperate need of rain. Years of unfavorable precipitation trends and more intense heat waves have fed directly to the state’s unrelenting, historic drought that has triggered dire water shortages.

But the past several weeks of rain and snow have “significantly reduced” the state’s drought intensity, according the US Drought Monitor’s latest report.

Extreme drought — the second-highest designation on the drought monitor scale — has nearly disappeared, according to the weekly analysis published Thursday. It is now confined to less than 1% of the state near the border with Oregon.

Only two weeks ago, more than one-third of California was in this extreme drought category.

The drought is not over for the state, however. Despite the epic rain and snow, more than 95% of California remains in moderate or severe drought, since moisture deficits have been baked into the landscape in some areas over the past three years.

Richard Tinker, author of this week’s drought monitor at the Climate Prediction Center, said there’s still quite a large deficit to make up as a result of the prolonged drought.

“These things always look very impressive when they happen — and this one certainly is impressive — but down the road, depending on how things go, they might not be quite the boon that you think that they are at the beginning,” Tinker told CNN. “But from a reservoir standpoint, we’d rather have it than not have it.”

The recent storms have been replenishing the state’s water supply, according to the state Department of Water Resources. California’s two largest reservoirs — Shasta Lake and Lake Oroville — have seen steep climbs and are inching closer to their historical average during this time of the year, which officials say is a much-needed improvement after remaining at critically low levels in the past year.

“Good news is that [the reservoirs] are off historic lows,” Michael Anderson, climatologist with the state’s Department of Water Resources told journalists Wednesday. “The challenge is that they still have a lot of recovery to make before they would be back to normal operating conditions — so something to be mindful of.”

Reservoirs still below average

As of Wednesday, Shasta Lake is at 44% of its total capacity, up 11% from where it was around this time last year, but still short of its historical average of 72%. Further south, Lake Oroville is at 49% of its capacity and still short of its historical average at this time of the year of 90%. Statewide, officials say California’s reservoir storage is at roughly 84% of average as of Wednesday — and it continues to rise with the storms.

Molly White, water operations manager for the State Water Project with the California Department of Water Resources, said they expect more significant increases in the coming days as more rain arrives.

“There are a few reservoirs that are at or above normal, but considering the great deficit we’ve had across the state and many of our reservoirs, we still have a deficit to go,” White said. “And we are filling them as we see all these storms come through.”

According to White, Lake Oroville storage levels are now higher than where they were in 2021 and 2022. Meanwhile, Shasta Lake storage has surpassed the level it was at during this time of the year last year. Shasta saw an increase of more than a quarter-million acre-feet in the last three days alone. (An acre-foot is the amount of water that would cover 1 acre of land a foot deep — roughly 326,000 gallons.)

Since the beginning of the December storms, Shasta Lake storage has gained at least 400,000 acre-feet. Meanwhile, Lake Oroville has seen an increase in lake elevation of roughly 650,000 acre-feet — and White said current forecast of inflows for Oroville in the next 10 days shows an additional 400-500,000 acre feet.

Standing at 215% of normal, the state’s snowpack gains so far this winter also have been “impressive,” Tinker said.

The Southern Sierra Nevada, in particular, is at 257% of normal, a significant shift for an area hardest-hit by the drought. Snow monitors across the state have registered what’s considered a full seasonal snowpack, which is what is typically expected by April 1.

“I would say even if things dry out, you’re not going to lose any ground really over the wet season,” Tinker said. “The snowpack has already been put there, so how effective that is at helping out reservoirs and stuff depends on how warm it is or the speed at which the snow is going to melt.”

High-elevation snowpack serves as a natural reservoir that eases drought, storing water through the winter months and slowly releasing it through the spring melting season. Snowpack in the Sierra Nevada accounts for 30% of California’s fresh water supply in an average year, according to the Department of Water Resources.

“We’d like that snow to stay there all the way to April 1, and maybe even grow a bit,” Anderson said.

Some relief, but ‘not as much as you’d think’

In 2021, Lake Oroville plunged to just 24% of total capacity, forcing a crucial California hydroelectric power plant to shut down for the first time since it opened in 1967. The lake’s water level sat well below boat ramps, and exposed intake pipes which usually sent water to power the dam.

Oroville’s low reservoir levels at the time pushed water agencies relying on the state project to “only receive 5% of their requested supplies in 2022,” according to the Department of Water Resources. Those water agencies were urged to enact mandatory water use restrictions to make their available supplies last through the summer and fall. Expecting another dry year, that 5% allocation was initiated last December, as the storms approached.

“We’re assessing and crunching the numbers on what these recent storms could do for the allocation,” White said. “At this point, we’re still below average in Oroville, although we’re gaining and it’s great to see that deficit gap slowly close.”

Groundwater across the state is also being recharged from the barrage of storms. Some cities that rely on groundwater aquifers for residential and agriculture use are beginning to capture water surplus from reservoirs such as the Folsom reservoir to fill the wells.

“I’d expect you’d see in a month or so, my gut feeling and I can’t say this for certain, you’ll see a pretty significant increase [in groundwater],” Tinker said. But still, he said, “It’s not as much as you think based on how extreme the conditions have been.”

Southern California also faced major water shortages as a result of the drought. But with the recent storms, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power estimated that about 10.6 billion gallons of stormwater had been captured between October 1, 2022, and January 10, 2023. That’s enough water to fill 16,000 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Citing the city’s water crisis, Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass said in a statement that the city has “set a goal to maximize on-site rainwater capture because that is the only way to sustain our city in the future.”