It’s Thursday. The Christmas storm that dumped many feet of snow across most of America was mostly over by Monday. Still, Southwest Airlines canceled another 2,300 flights today, long after its rivals had resumed normal service.

The airline said it is set to resume normal schedules on Friday. Why did Southwest take so long to get its operations back on track?

Southwest got unlucky with the location of the storm and its timing. The company also has a unique operations model, focused on smaller planes going to smaller cities, that failed spectacularly when America went into a deep freeze and was blanketed with snow. And outdated scheduling technology left Southwest scrambling to match crew with planes.

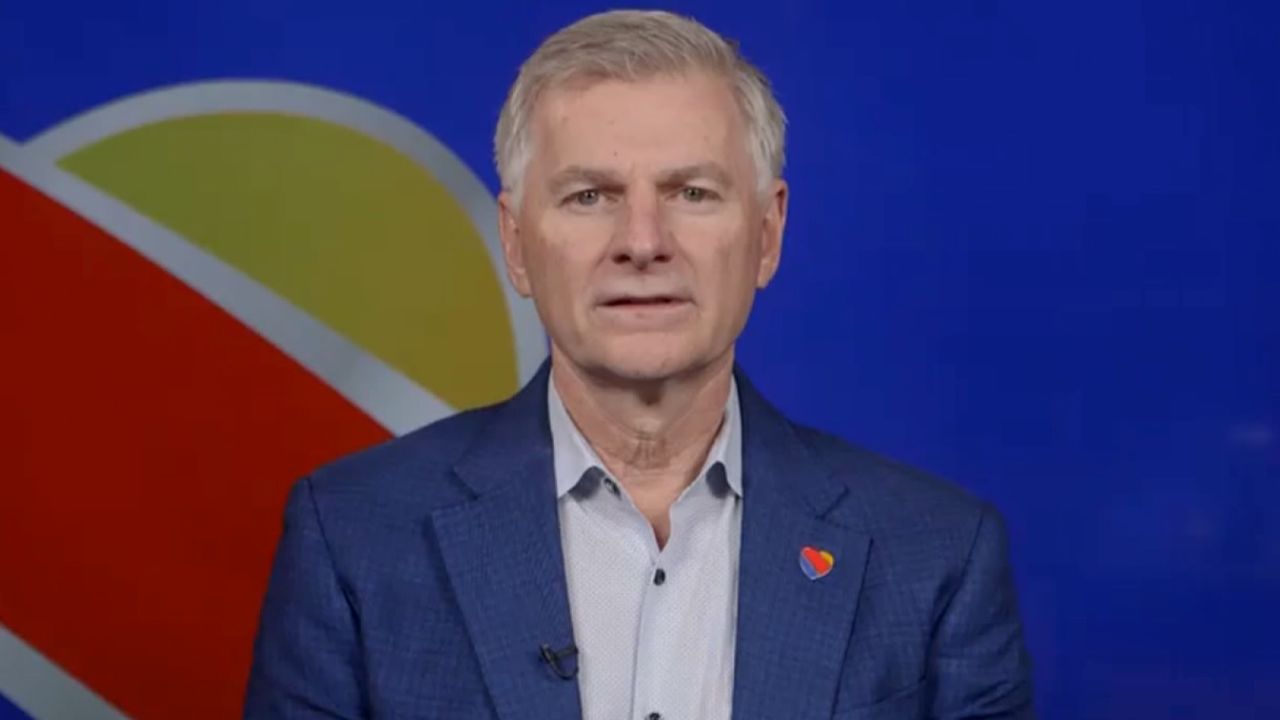

The airline purposefully reduced its flight schedule by two thirds this week to reset its operations, which CEO Bob Jordan likened to re-assembling a giant puzzle. Southwest aims to to resume normal service by the end of the week.

Are you stranded in an airport because of Southwest? Share your story.

Bad luck

The storm hit Chicago and Denver hard, where Southwest has two of its biggest hubs – Chicago Midway airport and Denver International airport. And the so-called “tripledemic” has been surging across America, leaving people and their families – including workers at Southwest and their families – sick with Covid, the flu and RSV.

Southwest said that prior to the storm last week, staff levels at the Denver airport became so low that it enacted “operational emergency” staffing procedures. Denver quickly developed into one of the nation’s biggest problem spots for cancellations.

Although Southwest says it was fully staffed for the holiday weekend, illness makes adjusting to increased system stress difficult. Many airlines still lack sufficient staff to recover when events like bad weather cause delays or flight crews max out the hours they’re allowed to work under federal safety regulations.

Operations snafu

Southwest’s schedule includes shorter flights with tighter turnaround times, which caused some of the problems during the storm. Unlike its rivals, which operate with a “hub-and-spoke” model, Southwest prides itself with a “point-to-point” business strategy that allows passengers to travel directly between smaller markets.

“We don’t have the normal hub like the other major airlines do,” Capt. Mike Santoro, vice president of the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association, told CNN Tuesday. “We fly a point-to-point network, which can put our crews in the wrong places, without airplanes.”

United, American and Delta typically fly from smaller markets to hubs, requiring passengers flying between small cities to change planes. But that model has the operational advantage of quickly flying crews and planes out of the hub to where they’re needed.

Southwest’s “point-to-point” model involves planes flying consecutive routes and picking up crews at those locations.

“When they have cancellations in one area, it really ripples through, because they don’t necessarily have their crews and their pilots in the right positions,” said Jeff Windau, senior equity analyst of equity research for Edward Jones. “They just kind of build on from city to city to city, and when that gets disrupted, it’s very difficult to get the operations flowing smoothly again.”

Santoro said Southwest’s meltdown was the worst disruption he’d experienced in 16 years at the airline.

Bad tech

Southwest’s outdated scheduling software couldn’t keep up with the constant changes, and quickly became the main culprit of the cancellations once the storm cleared, according to a transcript of a call Southwest Chief Operating Officer Andrew Watterson conducted with employees that was obtained by CNN from an aviation source.

Watterson explained that Southwest’s crew schedulers worked furiously to put a new schedule together, matching available crew with aircraft that were ready to fly. But the Federal Aviation Administration strictly regulates when flight crews can work, complicating Southwest’s scheduling efforts.

“The process of matching up those crew members with the aircraft could not be handled by our technology,” Watterson said.

Southwest ended up with planes that were ready to take off with available crew, but the company’s scheduling software wasn’t able to match them quickly and accurately, Watterson added.

“As a result, we had to ask our crew schedulers to do this manually, and it’s extraordinarily difficult,” he said. “That is a tedious, long process.”

Watterson noted that manual scheduling left Southwest building an incredibly delicate house of cards that could quickly tumble when the company encountered a problem.

“They would make great progress, and then some other disruption would happen, and it would unravel their work,” Watterson said. “So, we spent multiple days where we kind of got close to finishing the problem, and then it had to be reset.”

In reducing the company’s flights by two thirds, Southwest should have “more than ample crew resources to handle that amount of activity,” Watterson said.

What’s next?

Southwest says it is confident it will soon resume normal operations. It has just 39 cancellations planned Friday, according to flight tracking site FlightAware.

Mike Santoro told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer Wednesday that pilots have been told the airline is planning for a “mostly full schedule come Friday.”

But now the company faces an investigation by the Department of Transportation and the Denver airport.

Wall Street expressed concern that the debacle could cost Southwest. Investors sold off the stock, erasing $2 billion in market value from the company’s shares over the course of a week. The airline’s stock price bounced back nearly 3% Thursday, but remains down about 9% since the closing price on December 23, just before the mass cancellations.

– CNN’s Ross Levitt, Greg Wallace and Alicia Wallace contributed to this report