Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

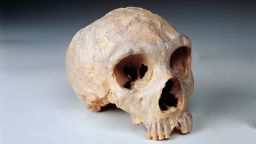

Meet the Neanderthals of Chagyrskaya Cave.

The riverside hunting camp in the foothills of the Altai mountains in Siberia was home to a tight community of about 20 inhabitants about 54,000 years ago, including a father and his teenage daughter, a young male who might have been a nephew or a cousin to them, and an adult female second-degree relative — perhaps an aunt or a grandmother.

The girl likely would have moved away from her father and family group when she found a mate. Had she been a boy, like her young cousin, she likely would have stayed put. However, the communities she migrated into probably would have contained familiar faces.

These are some of the intimate details of Neanderthal family and social life revealed by a study of ancient DNA that belonged to 11 former residents of Chagyrskaya Cave, as well as the remains of two others from the nearby Okladnikov Cave.

It’s the oldest known family group and the first time scientists have been able to directly document the fabric of a Neanderthal family and community, making our ancient cousins seem much more human.

“The fact that they were living at the same time is very exciting. This means that they likely came from the same social community. So, for the first time, we can use genetics to study the social organization of a Neandertal community,” said study coauthor Laurits Skov, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, in a news release. (“Neandertal” is an alternate German spelling.)

Genetic threads

The researchers extracted DNA from 17 bones and teeth that once belonged to seven male and six female Neanderthals, of which eight were adults and five were children.

They were able to unravel multiple threads of genetic ancestry: mitochondrial DNA, which follows the maternal line; Y chromosome DNA, which is inherited through the male line; and nuclear DNA.

In the mitochondrial DNA, the researchers found several heteroplasmies — distinctive genetic signatures that only persist for a small number of generations — which were shared between individual Neanderthals. This phenomenon, the reseachers said, suggested that the Neanderthals that they studied from Chagyrskaya Cave must have lived and died around the same time.

They also found that the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome DNA was a lot lower than that of the mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mothers. The study calculated that, in this group, two male individuals could expect to share an ancestor around 450 years before they lived. By contrast, the equivalent estimate for female individuals was around 4,350 years.

The researchers said the best explanation for this was that more of 60% of the female Neanderthals in the small Chagyrskaya group had migrated from another community. This social structure is common among present-day hunter gatherer societies and is known as patrilocality.

More broadly, the community had extremely low genetic diversity — much lower than any recorded for any ancient or present-day human community, the study said. The level of diversity was more similar to the group sizes of endangered species on the verge of extinction, such as mountain gorillas, which have a population of around 1,000.

However, Chris Stringer, research leader in human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London, who wasn’t involved in the research, said that the lack of genetic diversity wasn’t necessarily a significant factor in the extinction of Neanderthals, who disappeared around 40,000 years ago. He said other Neanderthal sites that were active around the same time as the group studied, such as Vindija in Croatia, indicate larger and more diverse populations.

The study authors said that the family group they had uncovered might not be representative of the social lives of the whole Neanderthal population. They recommended future research that includes the genetic sequencing of more Neanderthal individuals and communities.

First family snapshot

The inhabitants of the two caves likely interacted — trekking to the same sources of rock to make their stone tools — supporting the the genetic link between them. The Neanderthals hunted ibex, horses, bison and other animals that traveled through the river valleys the caves overlook.

Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov are within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of Denisova Cave — one of the most important locations in the study of human evolution. That site was occupied by Neanderthals, early modern humans and Denisovans, a more recently identified type of extinct human that was discovered from DNA retrieved from a single pinkie finger.

Svante Pääbo, another coauthor on the Chagyrskaya study, sequenced the first Neanderthal genome in 2010, work for which he received a Nobel Prize earlier this month. Since that initial sequencing, genome-wide data has been recovered from a total of 18 Neanderthals. The new study adds another 13 — a major technical achievement, said Lara Cassidy, an assistant professor in the Department of Genetics at Trinity College Dublin, who wasn’t involved in the research.

“What makes this work particularly remarkable is that the sequenced individuals are not scattered widely across the vast expanse of Neanderthal existence, but are concentrated at a specific point in time and space, thus providing the first snapshot of a family group,” she said in a commentary published alongside the study.