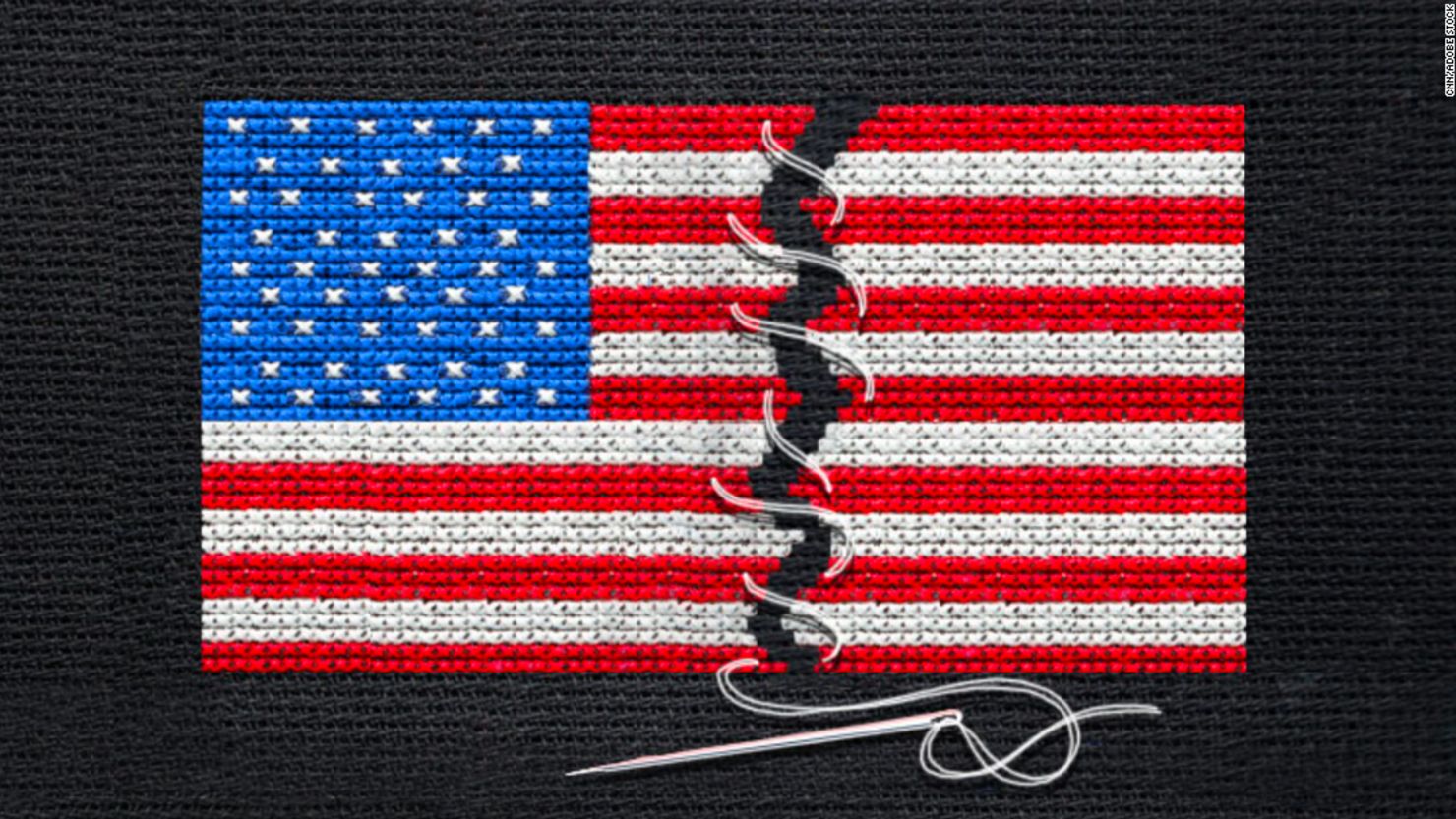

Editor’s Note: This roundup is part of the CNN Opinion series “America’s Future Starts Now,” in which people share how they have been affected by the biggest issues facing the nation and experts offer their proposed solutions. The views expressed in these commentaries are the authors’ own. Read more opinion at CNN.

Though Americans don’t agree on many political issues, there is one issue both Democrats and Republicans acknowledge poses a major problem: the state of American democracy. According to a recent Quinnipiac University poll, 69% of Democrats and 69% of Republicans think the nation’s democracy is on the brink of collapse. And the figure for independents, 66%, isn’t much better.

This fear, if actualized, would have ripple effects around the world, given that so many nations look to the United States to be a global leader in democratic efforts. But it also has very real implications for our country’s immediate domestic politics and policy – as evidenced by the recent attacks against election officials across the country.

The threats after the 2020 presidential election were so serious, writes Philadelphia City Commissioner Lisa Deeley, that “I had two plain-clothes Philadelphia police officers assigned to follow me wherever I went – including the bathroom.”

We turned to a group of experts and asked what can be done to fix what is broken and restore faith in democracy.

Bill Bishop: This 1950s psychology study holds the answer

Social psychologist Muzafer Sherif brought two highly similar groups of 11- to 12-year-old boys to Oklahoma’s Robbers Cave State Park in 1954. His intention was to study how hostilities arise between groups.

The boys arrived on separate buses and camped in different areas. One group decided to call themselves the Eagles; the other, the Rattlers. When the groups met, they fell into conflict. First, there was verbal sparring and then physical confrontation.

Sherif changed the terms of the experiment. He didn’t bring the boys around a campfire to express their feelings – polite chatter wasn’t the answer. Sherif gave both groups a problem to solve. He had jammed the camp’s water supply. If the boys wanted water, they would have to work together to fix the jam.

The boys collaborated on several problems. The hostilities dampened, and they stopped calling each other names. Several even asked if they could ride home together on the same bus.

Since the mid-1970s, Americans have been self-segregating. We live in neighborhoods, go to churches, read news and join clubs that are increasingly politically homogenous. We even date and marry within our chosen party. We are Rattlers and Eagles – and the consequences in 2022 are the same as in 1954.

What can we do? Mandatory national service. For a year or two, we would join others – a tossed salad of class, race, religion, party and way of life – to work on a problem facing the country. Not talk – do.

It could be through military service or a new version of the Appalachian Volunteers, the Peace Corps or Civilian Conservation Corps. But everyone at some point – Rattlers and Eagles – would have to work together to make the United States a better place.

Studies of World War II support the notion that working together reduces tensions between groups that might otherwise be hostile toward one another. White troops who fought alongside Black soldiers held less racial animus post-war. The same was true with White merchant marines who served with Black sailors.

So let’s carry that lesson into the present day. And when our time of service is up, we just might choose to ride the same bus home together.

Bill Bishop is author of “The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart.”

Fatima Goss Groves: Build a representative judicial bench

Democracy is broken because our trust is broken.

From overturning access to reproductive rights to upholding state laws that suppress the right to vote, federal courts – in particular, the Supreme Court – keep making decisions that most Americans simply do not support.

It’s only natural that this would erode trust. But it’s not just that some of these decisions call the rule of law into question – it’s that it appears our judiciary isn’t really listening to how the law is lived for each and every one of us.

And that contrast is made all the more stark when the courts are compared to the communities directly impacted by their decisions. The majority of federaI judges are White and male. They’re making decisions for communities they have often never been a part of – and that can have huge and irreparable implications, particularly for women and people of color.

We are in a pivotal moment. This session, the Supreme Court is hearing cases on affirmative action, voting rights and LGBTQ+ discrimination. We need a diverse judiciary – across all levels of the federal government – that gives the public confidence that the judges who hold our fates in their hands are seeking to fully understand the parties before them and are intent on reaching more fair-minded and informed decisions.

President Joe Biden feels this urgency and remains committed to judicial diversity. His appointment of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman on the Supreme Court, was a monumental milestone. And, as reported this July, 68% of Biden’s judicial nominees confirmed by the Senate are Black, Hispanic or Asian American.

This fall, we’re calling on the Senate to confirm all of Biden’s nominees – not just for the sake of the courts, but for the urgent and long overdue sake of restoring the public’s trust.

Fatima Goss Graves is the president and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center.

Joe Plenzler: Enlist veterans as election workers

Despite polling that indicates Americans think democracy is on the brink of collapse, we all have a choice. We can either cower before the challenge, or we can act to support, defend and strengthen our experiment in democracy.

After spending two decades serving as a US Marine, I’ve chosen the latter approach. I now belong to We the Veterans, a nonpartisan pro-democracy group committed to building a more perfect union. We believe that positive civic engagement is an antidote to political tribalism and extremism – and that veterans can be a part of the solution.

More specifically, veterans can fill the poll worker deficit currently facing our country. Democracy runs on elections, and elections run on volunteers. If a community does not recruit enough volunteers, it will have fewer polling stations, longer lines and potentially disenfranchised voters.

The pandemic and threats of political violence have severely diminished volunteerism within the traditional cohort of election poll workers, many of whom are 61 years of age and older. According to one estimate, the US requires more than 1.1 million volunteer poll workers to administer elections, and experts now project a shortage of about 130,000 going into November.

To meet this challenge, We the Veterans has launched its first nationwide public awareness campaign called Vet the Vote to recruit 100,000 veterans and family members to become poll workers in their communities. To date, we have recruited more than 60,000 poll workers.

The military – including its veterans – is one of the most trusted institutions in our society, and it is our hope that when Americans see their veterans conspicuously serving in their polling stations, it will increase their faith in their electoral system and its outcomes. Additionally, veterans are trained to deescalate moments of tension and may be best suited to address any potential threats at the polls.

Joe Plenzler is a 20-year veteran of the US Marine Corps who served in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is an entrepreneur and an election judge in Maryland. Plenzler is also on the board of We the Veterans and co-creator of Vet the Vote, a nationwide campaign to recruit 100,000 veterans and their family members to be poll workers.

Katherine Mangu-Ward: Stop treating politics like a pinata

If you lower a pinata packed with treats into a chaotic children’s birthday party, not only will you see some of the most astonishingly rapacious behavior imaginable, someone will almost certainly end up bleeding.

Every election, we essentially simulate those conditions in our democracy.

To retain whatever faith Americans have in our system of governance, we must arrest and reverse the dangerous tendency to turn everything into fodder for national political point-scoring. That means we must deregulate and devolve power to allow individuals to make their own choices about their love lives, their children’s education, the substances they put in their bodies, how they run their businesses – and many other topics about which Americans have widely varying and deeply held opinions.

As politics seeps into every single part of life, the stakes of our elections become untenably high. We must unstuff the pinata by reducing the size and scope of the government.

That means eliminating giveaways to corporations and other favored groups, as well as strengthening protections for economic and civil liberties in order to dramatically expand the sphere of privacy. With less power over others at stake, the temptation to cheat (or accuse the other side of cheating) is reduced.

This task isn’t easy, but it makes all subsequent policymaking much easier. I disagree with 69% of both Republicans and Democrats – nothing unusual there since I am a libertarian – and don’t think our democracy is on the brink of collapse. But I do think we are asking too much of our politicians and our political system, and that we shouldn’t be surprised when they act like spoiled children.

Katherine Mangu-Ward is editor in chief of Reason magazine and co-host of The Reason Roundtable podcast.

Larry Diamond: Eliminate the party primary

Today, our congressional (and state) representatives are nominated in low-turnout party primaries, in which the most highly motivated, partisan voters predominate. Increasingly, the nominees that emerge from that process – particularly in Republican primaries – are the most uncompromising.

Then, in November, elections are a “first past the post” contest only between the Republican and Democratic nominees, because a vote for a third-party or independent candidate is seen as wasted. This system stifles political choice and innovation – and leaves voters unsatisfied.

There is an alternative: ranked choice voting (RCV) with open primaries. Step one is a non-partisan “blanket” primary that advances the top four or five finishers to the November election. Pragmatic representatives couldn’t be knocked out at this stage because they would win enough votes from party moderates and independent voters to finish among the top four or five.

In the general election, RCV also would be used to choose the winner. Voters would rank their choices among the final five, and the winning candidate would need an absolute majority of votes. If no candidate won a majority of first-preference votes, the weakest finisher would be eliminated – and their preferences would be transferred to their second choices. This would continue until a candidate won a majority.

In this way, voters would be freed to vote for moderates and independents without fearing that they would be electing the candidate they most dislike. And pragmatism and flexibility would be encouraged because the process would tend to choose the most broadly appealing candidate.

Some states are already moving in this direction. As a result of a 2020 voter initiative, Alaska is using the “top four” RCV system this year for its executive, legislative and US House and Senate elections, and Nevada is voting this November on an initiative to adopt “top five” RCV voting for its future elections.

Larry Diamond is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, the Mosbacher Senior Fellow in Global Democracy at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) and a Bass University Fellow in Undergraduate Education at Stanford University.

Debra Cleaver: Make voting as easy as possible

The ability to vote is the most crucial component of a functioning democracy. Yet voting rights are under constant attack – more than 440 restrictive bills were introduced during the 2021 legislative session alone – and the integrity of election results are being called into question by some of the very people we elected into public office.

In order to ensure that US democracy doesn’t just survive, but thrives, we need first to rebuild trust in the electoral process itself to increase voter turnout. We can easily remove many of the existing barriers which have been built to impede one’s ability to vote by implementing modern, proven, common sense solutions.

For example, Arizona first pioneered online voter registration in 2002. Yet 20 years later, states such as Arkansas, Mississippi and Texas still refuse to offer this service. Online registration not only increases voter participation among under-represented minority communities but also lowers administrative costs for state and local governments.

Enforcing arbitrary registration deadlines weeks before an election only serves to compound the voter registration problem. These deadlines could be eliminated entirely if all states adopted same-day registration (or Election Day registration). Especially in states with strict voter ID requirements, such as Indiana, it’s a straightforward process to implement – and one which could enfranchise exponentially more voters than are disenfranchised by these ID laws. It’s also been shown to radically increase voter turnout and overall confidence in election results.

These simple and practical solutions must be made available to all eligible voters nationwide – both to increase voter participation and to rebuild their trust in our democracy.

Debra Cleaver is the founder and CEO of VoteAmerica, a nonprofit which builds technology to simplify political engagement, increase voter turnout and strengthen American democracy.

Ken Burns: Remind Americans of history’s greatest lesson

As told to CNN Opinion

Like many historians, I am an optimist. And American history provides a good baseline to assess the country’s potential. Given that the US has weathered three great crises – the Civil War, the Great Depression and World War II – there is reason to believe America can survive its latest crisis.

But this crisis – a loss of faith in American democracy – reflects a deep-seated anxiety about the very institutions this nation was founded on. In recent years, elements of democracy we took for granted, such as free and fair elections and the peaceful transfer of power, have been called into question.

That said, this isn’t the Weimar Republic in 1929, and there is still hope for American democracy. It begins by acknowledging that freedom has a cost, and it requires constant vigilance. In an era in which we are distracted by transactional opportunities – and not transformative ones – we lose sight of that fact.

We must ask ourselves where we wish to live. Think of the film “It’s a Wonderful Life.” The larger question of that film is whether we want to live in Bedford Falls, a largely welcoming and friendly town, or Potterville, a dark and hateful place. Most Americans would likely choose the former.

The only way we get to Bedford Falls is not through argument, but through story, conversation and connection. The novelist Richard Powers says, “The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.”

I’m in the business of trying to tell good stories. And my hope is that with each film I make, I move viewers. While I cannot control how they interpret the film, if I succeed, and the story lands some place inside of them, there is the potential for transformation.

Though every story is different, the one commonality among them is really American resilience – how in the face of adversity, much internally-borne, America managed to survive and thrive. And it certainly can again.

To paraphrase historian Deborah Lipstadt who appears in my latest project, “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” the time to save a democracy is before it is lost – and that requires people paying attention, filtering sources of news and beginning a politics of compromise built on conversation and storytelling now.

Ken Burns is an award-winning documentary filmmaker who has been making films for PBS for more than 40 years. He recently released “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” a three-part, six hour series that examines America’s response to the Holocaust.

Liza Donnelly: End ‘my way or the highway’ approach to politics

Liza Donnelly is a cartoonist and writer for The New Yorker and many other publications. Her history, “Very Funny Ladies: The New Yorker’s Women Cartoonists,” was published in 2022.

Mark Schmitt: It’s time for multi-party democracy

To break the deadly cycle of hyper-partisan polarization that threatens American democracy, we should have a system that creates and supports more viable political parties, simply by allowing parties to cross-endorse candidates.

Notice that I didn’t say that we need a new party. In the current system of winner-take-all elections and single-member congressional districts, just creating a party isn’t enough. A third party’s candidates will often be spoilers, in many cases benefiting the party its voters like least. Instead, we need a system that encourages the formation of one, three or many new and lasting parties that can better represent the complex views of all voters at the local, state and national levels.

With more than two political parties, some might represent factions of existing parties, such as non-MAGA Republicans or political moderates, while others might try to put particular issues on the agenda, such as universal basic income or marijuana legalization. They would bargain and form coalitions where they agreed – and differ where they didn’t – creating some of the dynamics of a parliamentary democracy.

There’s just one modest step that could help us move toward that ideal of multi-party democracy: States should allow parties to nominate anyone who is eligible for the office, even if they have already been nominated by another party. This practice, known as “electoral fusion,” would let new parties emerge that might sometimes cross-endorse candidates from one of the major parties, if they agreed with them, sometimes run their own candidates or sometimes stay out of a race altogether.

They wouldn’t be spoilers unless they chose to be. Using fusion, new parties could influence the two major parties, even if they weren’t yet big enough to win elections on their own. In states with a tradition of fusion, such as New York and Connecticut, the Working Families Party exercises such a role – and other parties have done so in the recent past.

All but eight states enacted laws to prohibit parties from cross-endorsing candidates – mostly around the turn of the 20th century. Letting parties nominate whomever they want, including a candidate from another party, is just a partial step toward the fluid multi-party democracy we’ve had in the past. But it would restore some of the bargaining and compromise that we’ve been missing for the last several decades.

Mark Schmitt is the director of the Political Reform Program at New America, a nonpartisan policy research organization.

Cecile Scoon: Each state needs a citizens’ initiative process

Threats to democracy are often examined through a national lens. However, a state approach can help strengthen democracy. For the past 50 years, pursuant to Florida’s state constitution, citizens have had a right to propose constitutional amendments for all Floridians to vote on. This process is called the “citizens’ initiative” process.

Through this process, Floridians have proposed whether to expand enfranchisement by restoring voting rights to persons who complete felony sentences, protect natural resources and ensure fairness in our political districts. These amendments, which all passed, have helped improve the lives of everyday Floridians and protect core facets of our democracy.

Unfortunately, our state legislature continues to attempt to chip away at our precious citizens’ initiative process by proposing legislation that ultimately seeks an all-out elimination of our ability to propose meaningful constitutional amendments or willfully ignores laws already adopted by voters.

An instance of this can be easily exemplified. In 2010, more than 60% of Floridians voted for a pair of “fair districts” amendments. These amendments require our legislature to draw nonpartisan redistricting lines and protect minority voting power by prohibiting the diminishment of voting strength for racial or language minorities.

In 2012, the state legislature blatantly ignored these requirements and passed partisan, gerrymandered maps. After the League of Women Voters of Florida and others sued and won, the Florida Supreme Court upheld these amendments in 2015 and fair maps were enacted.

In 2022, the Florida legislature has again gutted the same fair districts amendments. Legislators have enacted a map drawn by our governor that cuts minority voting power in half and gives a stark advantage to one political party. The League and others have sued the legislature once more for violating the will of the people. This case is ongoing.

It is time Florida’s legislators stop ignoring successful citizens’ initiatives and stop attempting to pass laws that further limit the process. Other states without any sort of similar process should consider creating their own to allow the direct voices of the people to be heard.

Cecile M. Scoon, a lawyer, is the president of the League of Women Voters of Florida.

Yuval Levin: Make Congress actually… work

There is no silver bullet for the problems confronting our democracy, but it is crucial to begin by recognizing that the political arena is intended to be a venue for disagreement and contention. Our political system now feels dysfunctional – not because we have forgotten how to agree with each other but because we have forgotten how to disagree constructively. Our two major parties spend too much time talking about each other and not enough time talking to each other.

At the national level, only Congress can change this. Congress is designed as an arena for productive disagreement, where members who represent the diversity of the American polity can make accommodations and come to agreements on behalf of their disparate constituents. When it works properly, Congress builds common ground in American life.

It would be an understatement to say that Congress does not do this today. And it is hard to see any way we could improve the health of our democracy without helping Congress function better. That could mean creating incentives for people more inclined toward legislative bargaining to run for Congress – for instance by experimenting with electoral reforms like ranked-choice voting. And it could mean reforming the work of the institution to make traditional legislative negotiation more appealing to the ambitious men and women who run for Congress – for instance by re-empowering the committees.

More specifically, committees in both chambers could be given some direct control of floor time, as happens in some state legislatures, so that the work the committees do wouldn’t feel like a dead end. Or Congress could eliminate the boundary between authorizing bills (which create programs) and appropriating bills (which spend money) so that all members, and not just the few who are appropriators, could be involved in meaningful legislating with real-world consequences.

There is no shortage of ideas about how to move power from party leaders to rank-and-file legislators, but there has long been a shortage of will. Yes, electoral and congressional reform isn’t exciting work, but it’s essential for the future of our democracy. And we should want our politics to be a little less exciting anyway.

Yuval Levin is the director of Social, Cultural, and Constitutional Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, where he also holds the Beth and Ravenel Curry Chair in Public Policy.

Michaela Terenzani: Model the change you wish to see in the world

When the Soviet Union collapsed some 30 years ago, people in Slovakia – my home country – looked to the American model of democracy as they built a new country founded on the principles of rule of law, human rights and civil liberties. The United States even aided those efforts, providing grants, training and exchange programs to guide our democratic efforts.

Of course, Slovakia is far from perfect. It has made mistakes along the way – including in its use of police violence against the Roma minority, which a 2014 State Department report said was a hindrance to its democratic development. But the US has also lost the high ground on this issue, particularly in the wake of George Floyd’s death and other incidents of violence by the police against American minority populations.

Simply put, how can we, Slovaks, accept advice or criticism from Americans, when they seem to be struggling with the same problems – and yet have a democracy that is over 200 years older than ours?

If the US wants to regain trust abroad – and to continue to inspire young democracies to believe in its form of governance – it needs to lead by example. In the case of police violence, there may not be a simple solution, but the US can put forward solutions.

President Joe Biden has taken positive first steps by signing an executive order advancing accountability in the police force and criminal justice system. Congress should follow with a more comprehensive bill that includes specific training, instruction and incentives for law enforcement facing this issue.

Americans may not realize how much those of us beyond their borders look to the US to lead the democratic world. But it’s a truth worth reminding my American friends. Your country can be imperfect, but it should be at the forefront of putting forward ideas that address those imperfections – and guiding young countries like mine toward becoming more inclusive nations.

Michaela Terenzani is the editor in chief of The Slovak Spectator, Slovakia’s English-language newspaper.