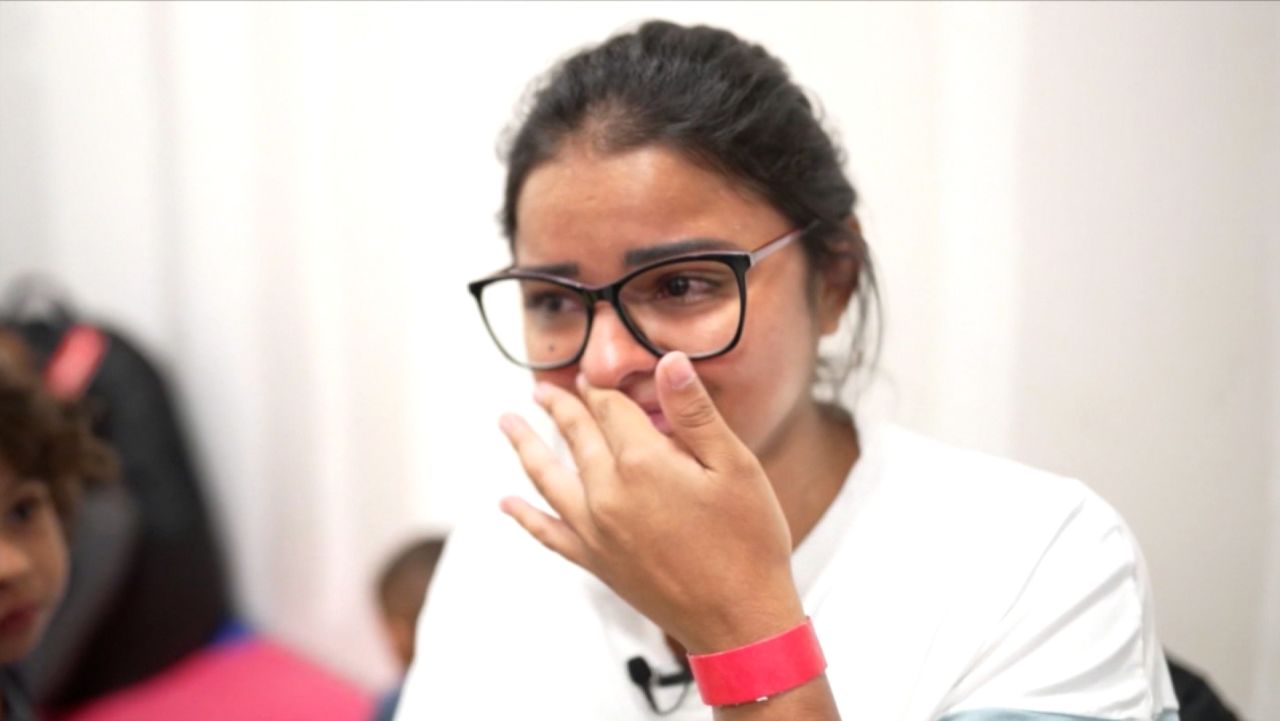

A 4-year-old girl wipes her mother’s tears inside a migrant respite center in El Paso, Texas. An act of love this mom says her daughter has made more times than she can remember since they left their native Nicaragua.

“She would tell me, ‘Mom, don’t cry.’” Yensel Castro says.

Castro wipes away more tears as she recounts the dangerous journey through Mexico with her daughter Camila.

“I witnessed a rape. It hurts my soul,” Castro says, crying. Little Camila looks at her mom with a sense of worry as Castro shares the horrific story.

Castro believes she was likely spared from rape on their journey because she had Camila with her. She says those are the risks women take to flee “dictatorship and much poverty” in her home country, where people have no “freedom of expression.”

The Castros were among the more than 580,000 migrants who were apprehended at the US southern border by Border Patrol, processed and released by immigration authorities into the United States this fiscal year pending immigration proceedings, according to US Customs and Border Protection data.

In August alone, immigration agents encountered more than 203,000 individuals at the southern border. Migrants from just three countries – Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba – made up about 56,000 of those encounters, or about 28 percent, federal data shows.

After an encounter at the border a migrant could be detained, immediately expelled from the US or released pending immigration proceedings.

Among the latest arrivals were the roughly 50 asylum hopefuls – mostly Venezuelans – sent from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, last month on flights organized by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis – part of a series of moves by Republican governors to transport migrants to liberal areas to protest what they describe as the failure of the federal government to secure the southern border.

Attorneys for the migrants have filed a class action lawsuit, saying they were misled in agreeing to the flights and had been told that they would arrive to find housing, jobs and help with the immigration process.

In response to the lawsuit, DeSantis’ office repeated what was previously said: The transportation of migrants from Texas to Martha’s Vineyard “was done on a voluntary basis.”

CBP Commissioner Chris Magnus says the latest wave of migration is mostly driven by people fleeing the “failing communist regimes” in Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba, which is complicating the processing and removal of those individuals once they arrive in the US, as they are generally not subject to Title 42.

Title 42 is the pandemic public health order that since 2020 has allowed immigration authorities to swiftly expel some migrants to Mexico or their home countries.

Rising levels of repression, food shortages and economic stability are motivating Venezuelans and Nicaraguans to flee their homelands said Doris Meissner, who directs US immigration policy work at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute in Washington. “These populations … require different kinds of response,” Meissner told CNN recently. “We have not established an asylum system that is in any way up to the level of the challenge that this change brought about.”

‘I don’t think this is sustainable long term’

In Del Rio, Texas, a small border town of about 35,000 residents, border patrol vans and buses constantly drop off migrants who have been processed by immigration agents at the Val Verde Border Humanitarian Coalition – the one migrant respite center in town. So far this year, more than 32,000 migrants have come through the center, a nearly 40% increase over last year’s total, according to Tiffany Burrow, the center’s director of operations.

“It’s just been so consistently growing that we’ve been able to adapt. But I don’t think this is sustainable long term,” Burrow told CNN.

El Paso, which is about 400 miles northwest of Del Rio, opened its own migrant respite center last month after shelters there reached maximum capacity and people started pitching tents on the street.

That’s where CNN first met Yensel Castro and her daughter, in the children’s play area of the center.

Castro’s voice broke and her eyes flooded with tears as soon as she started talking about her mother waiting for her in Chicago.

“I miss her so much,” she said between sobs, explaining that she had no money to travel to Chicago, where her mom was waiting for her. She said her mother left Nicaragua for Chicago five months ago and had been working to rent a home for the three of them.

A short drive from the respite center, El Paso’s Border Patrol Sector recently erected an open-air triage-style processing center under a highway overpass to help process migrants faster.

CNN got access to the center, which includes sections for intake, medical care and a waiting area, last month. Buses equipped with processing technology were parked on-site. Migrants don’t stay there very long, a few hours at the most. They are swiftly processed and divided into two groups, those who will be expelled to Mexico under Title 42 and those who are allowed to stay, pending their immigration proceedings.

“It’s like a mobile command center,” Magnus told CNN during an interview on-site. Magnus explained that people are given the opportunity to seek asylum, they are being vetted, and criminal backgrounds are being checked.

Far from the border, other Texas cities are responding to the crisis. San Antonio recently opened a respite center and another one is in the planning stages in Houston. Chicago, New York and Washington, DC have been forced to respond after several Republican governors transported migrants in buses to their cities unannounced.

America’s backlogged immigration system

The recently arrived migrants and asylum seekers are entering a highly complicated and backlogged immigration system. This fiscal year alone, U.S. immigration Courts recorded over 819,000 new immigration cases.

At the end of August, there were nearly 2 million immigration cases pending in immigration courts. That total includes 743,250 cases in which asylum claims have been made and are still pending, according to an analysis of government data by Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. There are hundreds of thousands more asylum cases going through US Citizenship and Immigration Services, the USCIS ombudsman told the National Law Review in July.

“It can take many years for the government to even call them [asylum seekers] for an interview or to go to court,” says Conchita Cruz, the co-executive director of the Asylum Seeker Advocacy Project (ASAP), a non-profit organization with more than 400,000 asylum seeker members from 175 countries.

In late May, the Biden administration launched an effort to speed up some types of asylum claims. The rule authorizes asylum officers – and not just immigration court judges – to consider asylum claims for those who assert a fear of persecution and pass the credible fear screening.

The effort, which is being implemented in a phased manner, is expected to shorten the process of some asylum applications, from several years on average to several months, according to the DHS.

But while that program rolls out, frustration over asylum application delays is compounded by another layer of the process. Individuals going through the asylum process have to apply separately for the right to work legally.

Cruz says asylum seekers are eligible to apply for a work permit 150 days after they file for asylum and, under the law, the federal government has 30 days to process applications.

At the end of March about 443,000 work permit cases were pending, according to a USCIS spokesperson.

That month USCIS established new goals to reduce the agency’s pending caseload, the spokesperson said.

ASAP and various other non-profit groups are in an ongoing legal battle with the federal government over work permit delays for asylum seekers. Cruz and her legal team are asking a judge to order USCIS to process its members’ work permit applications in 30 days, as the law requires.

“The government should comply, and process asylum seekers’ work permits as quickly as possible whether they’re forced to by a federal judge and a court order or not,” Cruz said.

In a statement to CNN, USCIS said the agency does not comment on issues directly related to pending litigation; but the agency acknowledged the “historic volumes of employment authorization requests” and noted its efforts to curb delays.

“USCIS set new agency-wide backlog reduction goals, expanded premium processing to additional form types, and implemented efforts to improve timely access to employment authorization documents. The agency remains committed to upholding America’s promise as a nation of welcome and possibility with fairness, integrity, and respect for all we serve,” a spokesperson told CNN by email.

The faces of America’s new asylum seekers

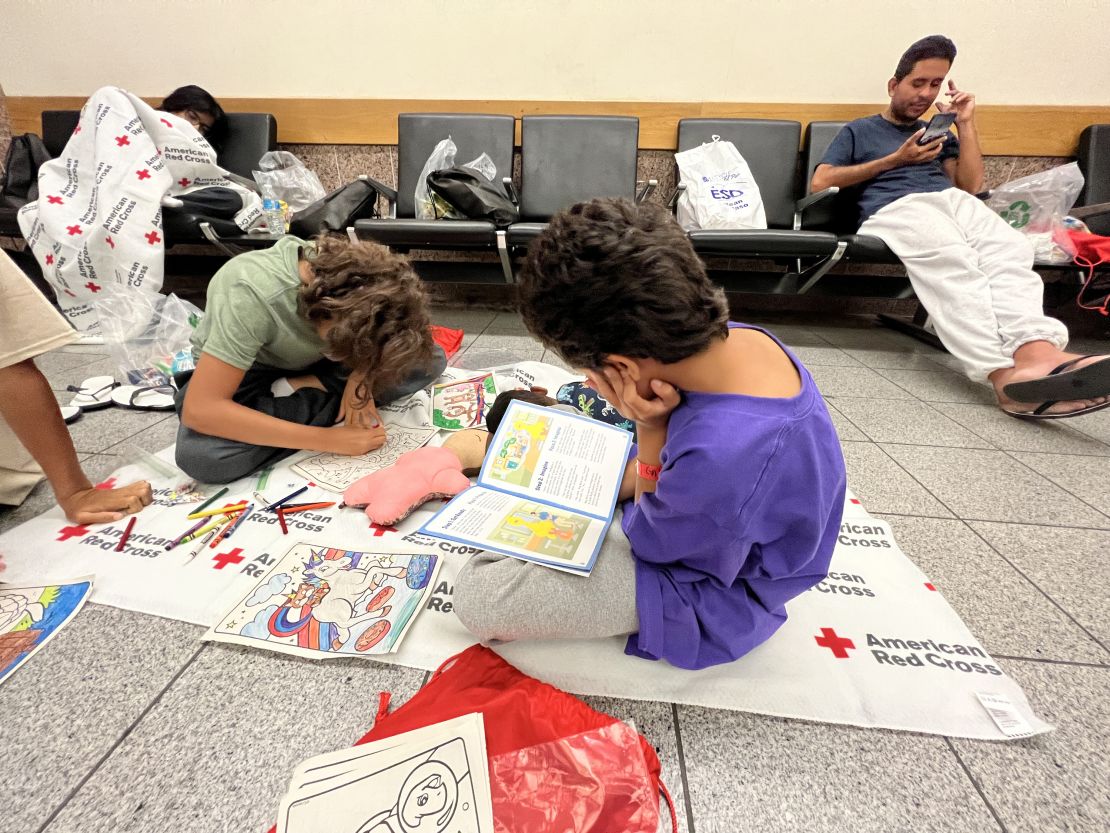

CNN has met dozens of migrants and asylum hopefuls in respite centers and shelters along the US southern border in the past few months. It’s at these centers that migrants get the opportunity to charge their cellphones, contact family to let them know they’ve been processed by immigration authorities and released into the United States, and where they take buses and planes to the interior of the country.

Ismael Martinez says he was a professional artist from Venezuela. He was processed by immigration authorities in Texas in April. He has since moved to New York, where he is selling hand-made jewelry on the street. He is renting a room for $1,000 per month. He has started his immigration proceedings and is waiting to file his asylum claim.

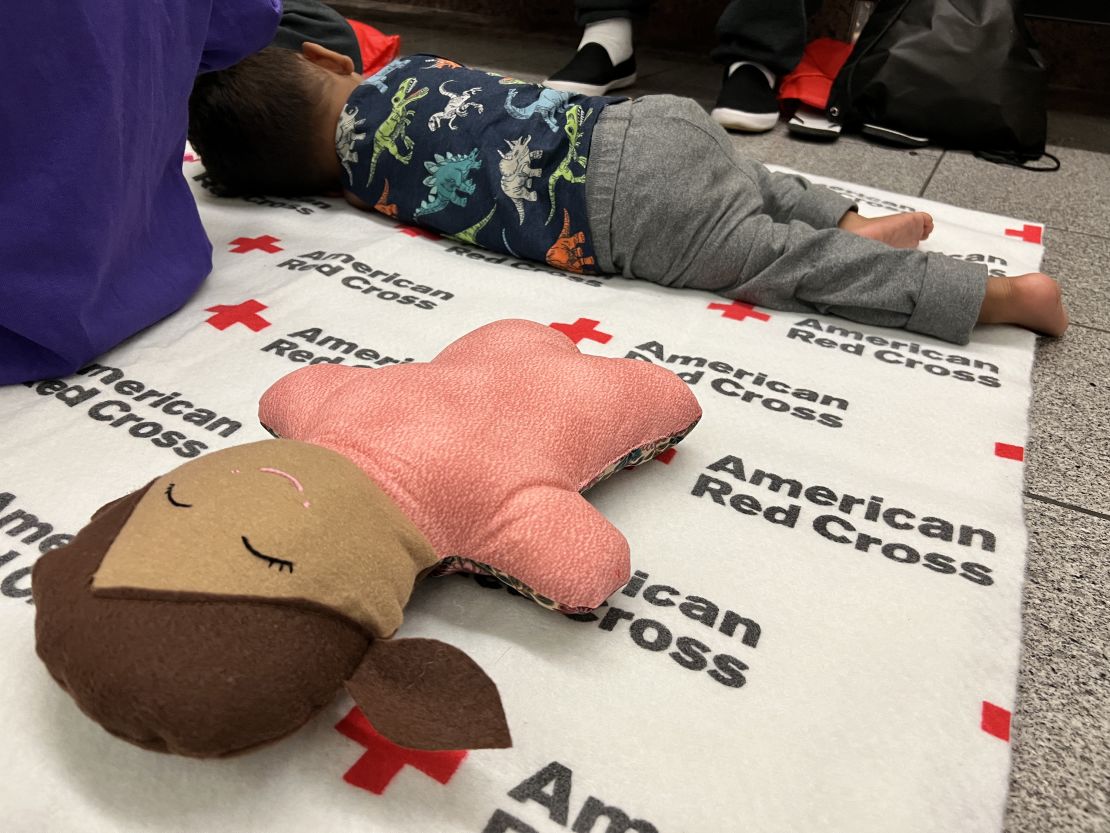

Franklin Delgado and his four children, ages 1 to 12, were processed by immigration authorities in El Paso last month. He says his wife couldn’t make the dangerous journey from Venezuela on foot because she is partially paralyzed. The family slept at the airport while they waited to fly to Atlanta. Delgado plans to start his immigration proceedings and enroll the children in school.

Jessy Amaya says he was a paramedic in Venezuela before he migrated to the United States in April. He lived in a homeless shelter in San Antonio for a while until he started working construction. Since then, he has purchased a vehicle to get around and rented a two-bedroom home for $800 per month. He has started his immigration proceedings and is waiting to file his asylum claim.

‘I’m starting from zero and it’s very tough’

For Yensel Castro, the migrant who said she witnessed the rape on her journey to the US with her child, reuniting with her mother in Chicago has been a rollercoaster of emotion. She was able to catch a bus, provided by the City of El Paso, the day she spoke with CNN. But the reunion was not what she expected. Castro says she was surprised to learn that her mom was very sick with arthritis and can no longer work.

“I’m in a very complicated situation,” Castro says.

Castro says she was processed by immigration authorities and released into the country last month. But she still has to go through her immigration proceedings, file an asylum application and get a work permit. And she is responsible for taking care of both her ailing parent and Camila.

“I thought it would be easy, that upon arriving I’d be working the next day,” Castro said. “I’m starting from zero and it’s very tough.”

Castro says she’s so desperate for help that when a woman she met at the grocery store offered her a bag of hand-me-down clothes for Camila, she walked for two hours, one hour each way, to get the items.

Once home, Castro showed her daughter each piece of clothing one by one. She took video of the moment and shared it with CNN.

Camila’s face lit up with excitement when her mom pulled out a long-sleeved shirt with a Christmas tree surrounded by presents and a puppy.

“Do you like it?” Castro asked.

“Yes,” Camila said. “It fits me.”

In the video, Camila holds up the shirt basking in joy that seemed unimaginable just a few days earlier at the migrant respite center – where her journey in the US began.

CNN’s Rosalina Nieves and Julia Jones contributed to this report.