A Nobel Peace Prize will be awarded in Norway on Friday, as Europe’s biggest war for seven decades rages on the continent.

Russia’s ongoing conflict in Ukraine means that this year’s announcement will rank among the most closely watched – and complicated – decisions made by the Norwegian Nobel Committee in recent times.

The award of the peace prize – one of humanity’s most coveted accolades – often serves as an offer of hope in uncertain times. But experts in the fields of peace and security warn that the bleak geopolitical picture may muddle 2022’s award.

“Sometimes, it’s hard to figure out who might get the prize because there are so many possible candidates,” said Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

“This year, it’s hard to figure out who might get the prize because there’s so little good that is happening in the world of peace and security,” Smith told CNN.

The Nobels are notoriously difficult to predict, and the thought process behind each selection is shrouded in secrecy. But experts have highlighted a short list of frontrunners – while reserving the right to be surprised by a left-field decision.

The impact of the war in Ukraine

No peace prize was awarded throughout most of the First and Second World Wars, and on a handful of other occasions. But the prize has frequently been used to highlight other ongoing conflicts, or to provide a beacon of hope when the world encountered grim times.

That question will have been front and center among decision makers in Oslo, Norway, who have been tasked with picking a symbol of peacemaking even as a bordering country wages war on the continent.

The conflict “would weigh enormously on their minds,” Smith said.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky sits atop many bookmakers’ list of favorites to win the prize, and some companies also list as frontrunners the general population of Ukraine and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which has aided people displaced by the war.

There have been previous occasions where the committee has become involved in ongoing conflicts.

“Sometimes the prize is about sending a message in a quite specific sense,” Smith said. He cited the 1993 award to Nelson Mandela and Frederik Willem de Klerk, who at the time were negotiating for South Africa’s first open elections following the end of apartheid.

“That process was ongoing and the committee at the time wanted to influence it,” he explained.

But bookmakers’ odds are rarely a reliable guide to the victor, experts say, because they tend to overstate the relevance of topical events.

And an award that directly wades into the Ukraine conflict is considered unlikely.

“Zelensky is a war leader, and what is happening at the moment is war. You can admire or not admire the action he’s undertaking, but it’s about war and the armed defense of his country,” Smith said. “That’s a fact that should be respected in and of itself.”

“Hopefully, the war will come to an end and they will make peace,” he added. “If Zelensky or somebody else can contribute to making that peace, then there will be time to acknowledge that enormous achievement.”

Kremlin critics highly tipped

Critics of the Russian regime and its allies are among those many expect to clinch the award.

Alexey Navalny, the Kremlin critic and opposition leader who was sentenced to jail on fraud charges by a Moscow court this year, features atop many experts’ predictions.

Navalny is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s most prominent domestic critic, and his dissenting views have nearly cost him his life. He was poisoned with a nerve agent in 2020, an attack several Western officials and Navalny himself openly blamed on the Kremlin. Russia has denied any involvement.

After a five-month stay in Germany recovering from the Novichok poisoning, Navalny last year returned to Moscow, where he was immediately arrested for violating probation terms imposed from a 2014 case.

But some expect even his path to the award to be a narrow one. “Navalny I think is heroic, (but) he’s a political leader,” Smith said. That has not stopped some politicians, like US President Barack Obama, from being honored, but with Navalny imprisoned his opportunity for real-world peace-making may be considered too small.

“It’s a prize that is to be awarded not for how great you are, but for how great the things you’ve done are,” Smith said.

Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is also generally seen as a strong contender. The dissident was forced into exile in Lithuania after running against strongman leader and Putin ally Alexander Lukashenko in an August 2020 election denounced by the international community as neither free nor fair.

A joint win for Tsikhanouskaya and Navalny is predicted by Henrik Urdal, the director of the Peace Research Institute Oslo, who draws up a shortlist of frontrunners for the prize annually.

“Both Tsikhanouskaya and Navalny are vocal critics of the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Urdal wrote this year. “A shared Nobel Peace Prize between them would be seen as a clear protest of the Russian aggression and the assistance by Belarus, and as support of democratic and non-violent alternatives to Lukashenko and Putin.”

A surprise is possible

The Nobel Peace Prize is not always a reactionary award, and a strong possibility remains that the committee will look beyond the current geopolitical climate and highlight another field.

Some suggested the Covid-19 pandemic, which has rocked global security for the past two years, would factor into the mindsets of Nobel decision makers over the past two years – but instead, awards in 2020 and 2021 highlighted food insecurity and threats to press freedom, respectively.

This could be the year that efforts to end the pandemic are recognized – but it would set a drastic precedent since no previous awards have specifically focused on the arena of public health, Smith said.

When there are few obvious individuals expected to win, global institutions have frequently benefited. The United Nations, and several of its related humanitarian bodies, have earned the trophy, most recently the World Food Programme in 2020.

Urdal has suggested the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as a winner this year, should the committee decide to highlight conflict resolution.

“While a Nobel Peace Prize to ICJ would largely be seen as uncontroversial, on March 16 the court ordered Russia to ‘immediately suspend the military operations’ in Ukraine. The Nobel Committee could emphasize this ruling as an attempt to stop the illegal war,” he wrote.

Urdal also suggested Indian human rights activist Harsh Mander as a winner, and raised pro-democracy demonstrators in Hong Kong and figures resisting China’s suppression of Uyghurs as other names worthy of recognition.

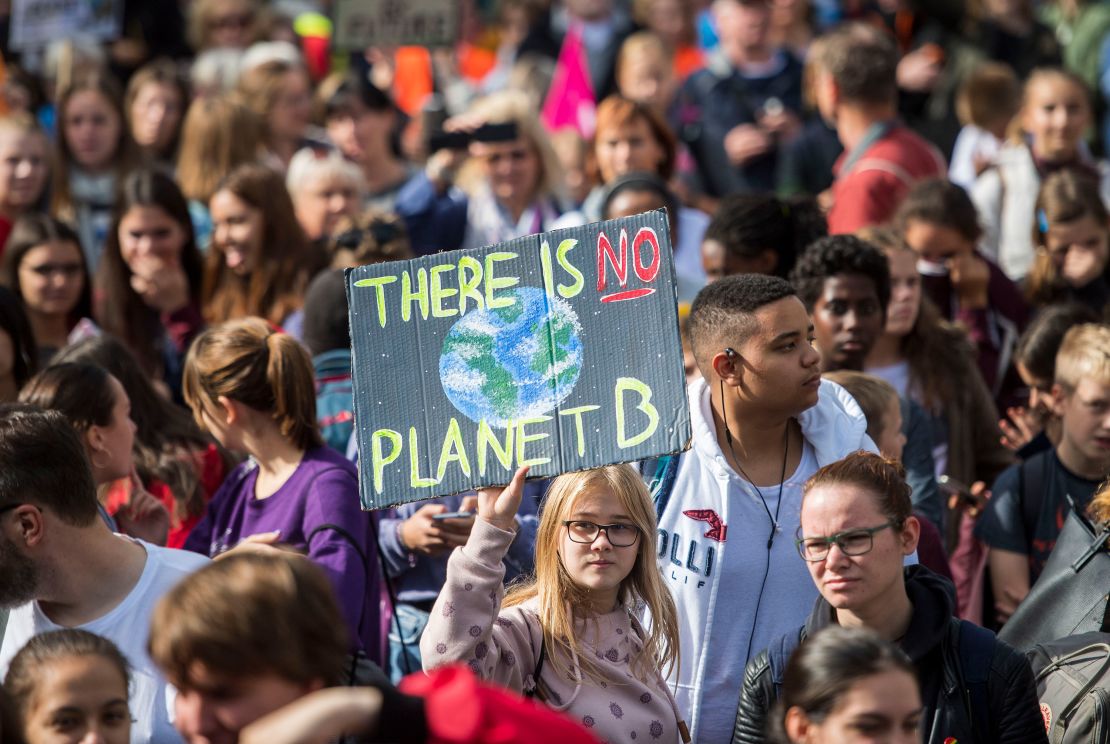

The committee may alternatively return to the theme of climate change if they struggle to find a peace-making accomplishment achieved in the past year. Teenage campaigner Greta Thunberg is perennially raised as a contender, along with several other climate activists.

But there remains a high likelihood that the name – or names – read out on Friday will be little-known to experts or viewers.

“One thing the peace committee has been quite good at doing, when it wants to, has been to really surprise us all,” Smith said. He raised Nadia Murad’s win in 2018 for working to end sexual violence as one such example.

“Perhaps they will take somebody who has been working quietly and without a lot of visibility for peace – maybe at a community level – and focus attention on that,” he suggested. “I quite admire them for the way that they do that.”