Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has joined an institution of isolated chambers and archaic procedures. It is also a place that has lost the public’s trust. So, as she navigates the cloistered corridors, she’ll also have to watch her footing in the ongoing debate over the institution’s legitimacy.

In some respects, Jackson begins the new session Monday with advantages her recent predecessors lacked. She moved into her expansive, freshly painted chambers weeks ago. She had the summer to bone up on cases. And she has hired, among her clerks, a lawyer who previously served the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

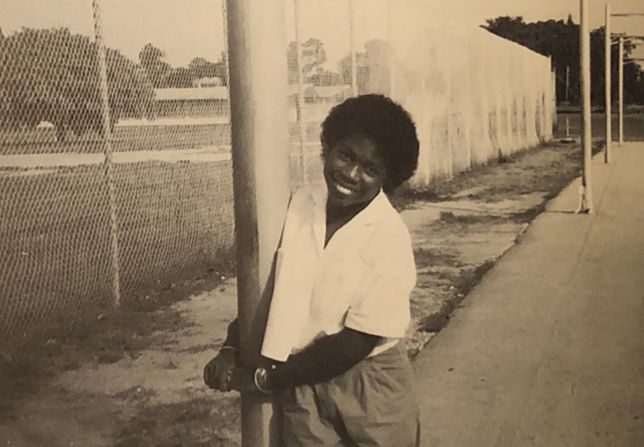

Jackson, 52, took the ceremonial oath on Friday but officially assumed her position on the nation’s high court in June and was able to begin reviewing the cases for the 2022-23 session.

RELATED: The Supreme Court is fighting over its own legitimacy

The three prior appointees – Amy Coney Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch – were seated as cases were already underway and had little time before facing difficult votes. Barrett and Kavanaugh were confirmed in October 2018 and 2020, respectively, after oral arguments had begun, and Gorsuch was seated in April 2017.

Once into a routine, justices say it can take years to build confidence.

“I do think it takes three to five years,” Stephen Breyer, whom Jackson succeeded, said in a CNN interview last year. “Justice (William O.) Douglas said three years, (David) Souter thinks it’s five. … I was pretty nervous the first three years at least, and maybe a little longer … Can I really do this job? And then you begin to absorb the mores of the institution.”

Those mores exist in an atmosphere distinct to the Supreme Court, one that can be disconcerting, irrespective of experience as on lower federal courts (as Jackson had for nine years) or service as a Supreme Court law clerk (as Jackson and five other current justices were early in their careers).

And here’s a new twist: Since last session’s decision reversing nearly a half-century of abortion rights, and other decisions rolling back precedent, public approval of the court has plunged.

A new Gallup poll shows a record high number of people, 58%, said they disapproved of the job the Supreme Court was doing.

Justices have gone public with conflicting views about such numbers and whether the court’s legitimacy can be questioned, escalating the tensions as they’ve gone along. This week Justice Samuel Alito warned of criticism that “crosses an important line.”

Jackson has not commented on the boiling issue and has no speeches scheduled for the remainder of 2022.

Her past judicial record would naturally align her with fellow liberal Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, who referred last year about the “stench” of politics permeating the court.

But it is not known how Jackson will present herself in the public eye regarding the ideological and partisan divisions.

It is difficult to know, more broadly, how Jackson may interact with fellow colleagues, beyond the geniality she showed at the Senate confirmation hearings last spring. She operated solo for eight years as a federal trial court judge in Washington, DC. Her few months on the US appeals court for the DC Circuit, hearing cases in three-judge panels, did not test her as dealing with eight colleagues on all cases will.

Hiring clerks and diving into the ‘cert pool’

At the outset, one of the most daunting tasks involves the screening of the hundreds of appeals (known as petitions for certiorari) received each week from people who have lost their cases in lower courts.

Jackson has joined the “cert pool,” by which justices’ law clerks band together to screen these petitions and write memos summarizing whether the cases should be granted and scheduled for oral arguments or outright denied.

The justices take up less than 1% of the cases that come their way, hearing and resolving only about 60 each annual session. Justices primarily look for instances in which lower courts have issued conflicting decisions (seeking to resolve those conflicts) or cases that test the reach of federal power.

The “cert pool” began in the 1970s as a way to ease the court’s workload, and not all justices have joined over the years. Some justices thought it would add a level of bureaucracy or lead to manipulation of the review process. For instance, Justice John Paul Stevens, who served from 1975 to 2010, never joined the pool.

More often than not, however, justices have joined the pool through the years, including Roberts, who himself was part of it when he served as a law clerk to then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist in 1980 and 1981.

Gorsuch is a more recent exception. He opted against it, and after a few years of participation in the pool, Alito has also pulled out.

Most new justices try to pick up at least one former clerk, and among the four law clerks that Jackson has hired for her inaugural term is Michael Qian, who worked for Ginsburg during a tumultuous 2019-2020 session that happened to be Ginsburg’s last. Two other Jackson clerks served with her when she was a district court judge.

Kagan, who had not been a judge on any bench before her 2010 appointment, succeeding Stevens, described recently, at a judicial conference in Big Sky, Montana, enlisting three clerks with prior experience, from the chambers of Ginsburg, Breyer and now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy. She said she depended on them – up to a point.

Whenever she would have to make a decision regarding an internal procedure, she would inevitably get three “entirely different” views. “So I would sort of listen to them, and say, ‘Why don’t we do that one.’ … Sometimes I would be happy with my choice, and other times we would do it that way, and I would think: that is the worst way of doing things.”

Seniority is everything

Seniority reigns at the Supreme Court. In the justices’ private conferences, held in an oak-paneled room off Roberts’ chambers, the justices proceed in order of rank as they offer their views of cases and cast votes, beginning with the chief justice.

Not only does she speak ninth, Jackson also has the junior-justice chore of taking notes of the proceedings. (No one other than the nine is allowed into these sessions.) If someone knocks on the door, to deliver a book, document or forgotten pair of reading glasses, answering the door falls to Jackson, too.

Her first session of oral arguments will be Monday, and she will take the freshman seat at the end of the bench, to the chief justice’s far left, next to Kavanaugh. Barrett will now be on Roberts’ far right. (The justices sit at the mahogany bench in alternating order of seniority: the more tenure, the closer to the chief justice, in the center chair, a justice moves.)

In the past, some new justices have held back at oral arguments, waiting to make sure more senior members can get their questions in. This has reflected personal style, rather than any ideology. Gorsuch, as well as Ginsburg, who served from 1993 until 2020, jumped into the fray early and often, while Alito, who joined the court in 2006, initially asked few questions.

In the beginning, Alito also had trouble with the microphone in front of him, sometimes accidentally hitting it with his hand or bumping his head against it. “It is in the way,” he told me in his early months regarding the placement of the microphone. “Then you can’t help hitting it when you gesture. It’s kind of awkward.” Alito used to lean in close to the bench. He now sits back a bit.

Beyond the new patterns in the justices’ consideration of cases, a delicate dynamic can emerge among the nine in extracurricular matters when a new justice arrives. Roberts himself told C-SPAN in 2009 that the arrival of a new justice can be “unsettling,” and in 2017, he and Gorsuch fell into some early squabbles, including over Gorsuch’s decision to skip a private justices’ session, soon after his confirmation, because of a previously scheduled commitment.

Back in the early 1980s, after Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman justice, joined the bench, she inadvertently irritated Justice Harry Blackmun by settling into a small justices’ private library.

Blackmun had been the only justice who used the private quarters at the time, and once O’Connor began using it, the sometimes-prickly Blackmun made sure she and the rest of the justices knew he considered it an intrusion.

But such griping eased over time. The justices, all appointed for life, often speak of learning to live with each other.

Breyer happened to succeed Blackmun in 1994. Asked this week whether his predecessor had any advice at the time, Breyer responded: “Justice Blackmun told me: “You’ll find this an unusual assignment.’”