Billionaire Elon Musk tweeted, not for the first time, that “population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming.” Climate change is a serious problem facing the planet and experts say it’s difficult to compare problems.

What is clear, demographers say, is that the global population is growing, despite declines in some parts of the world, and it shouldn’t be collapsing any time soon – even with birth rates at lower levels than in the past.

“He’s better off making cars and engineering than at predicting the trajectory of the population,” said Joseph Chamie, a consulting demographer and a former director of the United Nations Population Division, who has written several books about population issues.

“Yes, some countries, their population is declining, but for the world, that’s just not the case.”

Population projections by the numbers

The world’s population is projected to reach 8 billion by mid-November of this year, according to the United Nations. The UN predicts the global population could grow to around 8.5 billion in just 8 years.

By 2080, the world’s population is expected to peak at 10.4 billion. Then there’s a 50% chance that the population will plateau or begin to decrease by 2100. More conservative models like the one published in 2020 in the Lancet anticipate the global population would be about 8.8 billion people by 2100.

It’s true that what’s driving current population growth is not a higher birth rate. What drives global population growth is that fewer people are dying young. Global life expectancy was 72.8 years in 2019, an increase of nine years since 1990. That is expected to increase to 77.2 years by 2050.

Globally, the fertility rate has not “collapsed,” nor should it, according to the UN, but it has dropped significantly.

In 1950, women typically had five births each; globally, last year, it was 2.3 births. By 2050, the UN projects a further global decline to 2.1 births per woman.

In some countries, it is lower. In the US the 1950s, it was 3.6 births per woman, it slipped to 1.6 in 2020, according to the World Bank. In Italy, it was 1.2; in Japan, it was 1.3; in China, 1.2. In January 2022, the country announced the birth rate fell for the fifth year in a row, even with the repeal of the one child policy, allowing couples to have up to three children as of 2021.

“Virtually every developed country is below two, and it’s been that way for 20 or 30 years,” Chamie said. Most countries have gone through what’s called a demographic transition.

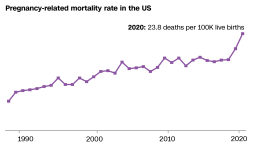

The only continent that hasn’t finished this transition, he said, is parts of Africa, where there are 15 to 20 countries where the average number of children couples have is five. But in those countries, children still face high death rates. The infant mortality rate for kids under 5 is 8 to 10 times higher than in developed regions, and maternal mortality is more than double, Chamie said.

If women in these African regions had more access to contraception, education, and health care, these problems could be addressed and the global population could decline further – but people would be better off in terms of individual health.

The ‘gold medal’ century

In terms of population growth, the 20th century was an anomaly.

“That century was the most impressive demographic century ever. It had more gold medals than all the other centuries,” Charmie said.

The human population nearly quadrupled, something that had never happened before in recorded history. That’s largely because of improvements in public health.

The world has antibiotics, vaccines, public health programs and improved sanitation to thank for people living longer and more mothers and children surviving birth.

With contraception, especially in 1964, when the oral pill was widely introduced in the US, couples were now better able to determine when and how many children they had.

“Contraception, the oral pill had a much more significant effect on the world than the car,” Charmie said.

As more women got an education, worked outside the home and got a later start on children in many countries with access to contraception, couples had fewer children and the population started to decline.

In 2020, the global population growth rate fell under 1% for the first time since 1950.

The picture in the US

In the US, the fertility rate is down in part due to what Ken Johnson, a senior demographer at the Casey School of Public Poilcy and a professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire, characterized as a “significant” decline in teen births.

“Most demographers would see that as a good thing,” he said.

He said the other driver was a decline in the number of births to women in their 20s. That trend has been around since 2008. People put off or decided not to have babies in part because of the recession, he said. Covid then exacerbated this trend.

Between July of 2020 and 2021, the growth rate of the US population was the lowest it’s been in probably 100 years he said.

“Is it a collapse of the number of births? No, I wouldn’t say that,” Johnson said.

He said there are a few factors at play in the low US growth rate: fewer births, fewer immigrants due to Trump-era policies, and more deaths as the US population is ages. Covid-19 contributed to higher deaths, too.

“It’s almost like a perfect storm if you will,” Johnson said. “Births are way down, Covid pushes deaths way up, and then immigration is quite slow, too, so it is no wonder that the population growth rate is so low when you bring all those factors together at the same time.”

Preventing population problems down the road

As the population ages and birth rates decline in some areas of the globe, that could put strain on social systems.

The share of the population over age 65 will rise from 10% in 2022 to 16% in 2050. That’s twice the number of kids under age 5.

Globally, the trick to make such a population age imbalance work, is that governments will need to be proactive, the UN says. Countries with aging populations need to adapt public programs that will support this growing population of older people. That means shoring up programs like social security, pensions and establishing universal access to health care and long-term care.

In the US, William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow with Brookings Metro, said he doesn’t see the need for more couples to have more babies to address the age imbalance in the United States. Policies that would support couples that want children – affordable daycare and family leave policies, for example – could help, but that that hasn’t made a big difference in terms of fertility rates.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Fertility is below the replacement rate in the US, meaning couples are having fewer than two children each, but the rate is not as low as it is in most of Europe, he said.

“I don’t think in the US it’s an issue of collapse, because we can certainly open the faucet for more immigrants anytime we want to,” Frey said. “We’ll have no paucity of people who want to come through the door to immigrate here in the future. Immigrants and their children are younger than the population as a whole and so that will help to keep the population from aging as well.”