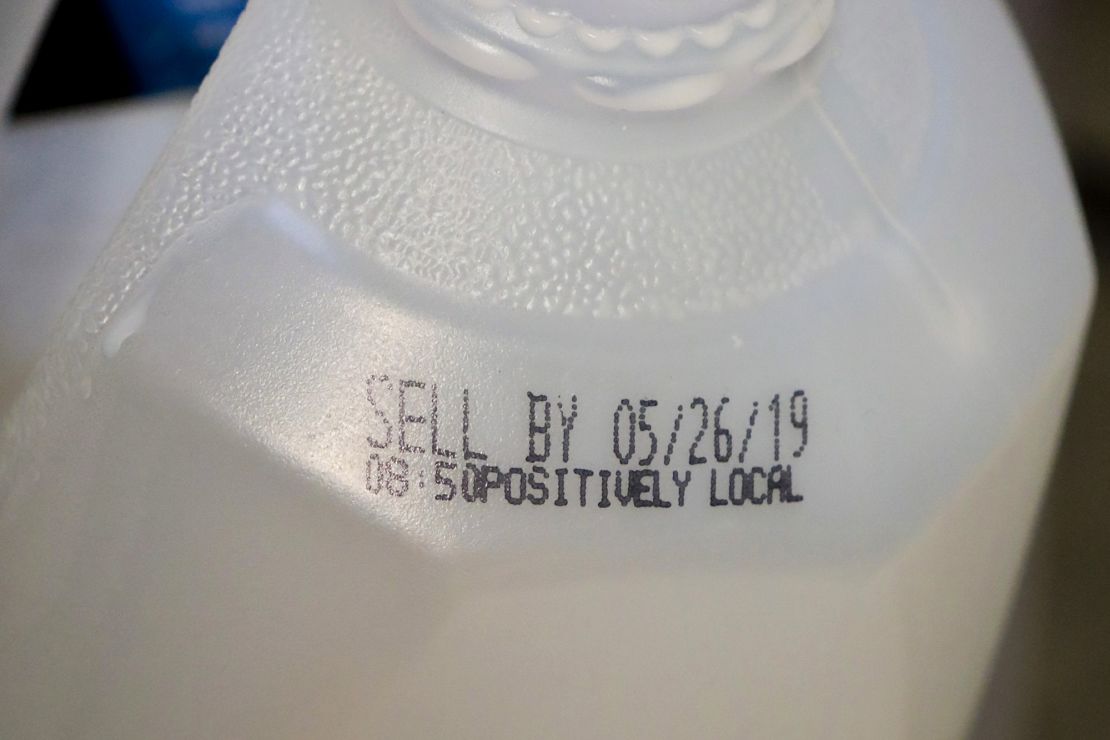

When you walk into a supermarket and pick up an item — anything from milk to cereal to a can of beans — you’ll likely see a little date on the package preceded by “enjoy by,” “sell by,” or a similar phrase.

You might think that date is the absolute last day that food is safe to eat. You’d be wrong. But you wouldn’t be alone in coming to that mistaken conclusion, because the system behind food label dates is an absolute mess.

There’s no national standard for how those dates should be determined, or how they must be described. Instead, there’s a patchwork system — a hodgepodge of state laws, best practices and general guidelines.

“It is a complete Wild West,” said Dana Gunders, executive director of ReFed, a nonprofit trying to end food waste. And yet, “many consumers really believe that they are being told to throw the food out, or that even when they don’t make that choice, that they’re sort of breaking some rule,” she said.

For food makers, sell-by dates actually are more about protecting the brand than safety concerns, explained Andy Harig, vice president of sustainability, tax and trade at FMI, a food industry association.

The sell-by date, often referred to as the expiration date, is the company’s estimate of when a food item will taste best, its optimal date. “You want people to eat and enjoy the product when it’s at its peak, because that’s going to increase their enjoyment, [and] encourage them to buy it again,” he said.

The main consequence of this unclear labeling? Food waste. Lots of it.

“Consumer uncertainty about the meaning of the dates … is believed to contribute to about 20 percent of food waste in the home,” the Food and Drug Administration wrote in a 2019 post.

Wasted food often ends up in landfills, making it a major contributor to climate change. By some estimates, food loss and waste makes up 8% of global greenhouse-gas emissions.

Wasting food also means wasting money, which many consumers can’t afford, especially now as grocery prices soar. And food that is thrown out is diverted from food banks, where it is desperately needed.

Making sense of dates

Though many companies put dates on their products, baby formula is the only food that is required to have use-by dates in the United States, said Meredith Carothers, a food safety expert with the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service.

Companies choose dates based on when they think an item tastes best. But FSIS has its own safety recommendations. Many canned goods can last on shelves for anywhere between one and five years, according to the agency, if properly stored. Under the right conditions, packages of rice and dried pasta can last about two years. The FDA offers food storage tips and guidelines on its website.

But the rules are wildly different for many perishables.

While consuming shelf-stable items after a “best if used by date,” is likely fine, fresh meat and poultry could go bad even before the date on the label. That’s because store refrigerators tend to be colder than our home fridges, explained Carothers.

Once consumers take meat and poultry home, they should follow home-storage rules, she said. The FSIS instructs people to cook or freeze some meats within two days of bringing them home from the store.

How we got here

Manufacturers began printing sell-by information on products in the early 20th century. At first, the date was written in code: Retail employees had to match each code to a date using a key, but to customers the codes were incomprehensible.

In the 1970s, grocery shoppers clamored for more information about the quality of food on supermarket shelves. Under pressure from activists, including the distribution of pamphlets deciphering sell-by codes, food makers began to put dates on their labels.

At first, this “open dating” tactic appeared to be working.

In February 1973, The New York Times ran an article headlined “Food Dating is Found to Please Customers and Reduce Losses.” The piece pointed to a study conducted by the USDA and the Consumer Research Institute, a group backed by food manufacturers, which concluded that open dating had slashed by half the number of consumer complaints of purchasing stale or spoiled food.

But by the end of the decade, those examining the system were less convinced of its merits.

A 1979 study by the now-defunct Office of Technology Assessment noted that open dating may not have been the right way to quell consumer fears.

“There is little evidence to support or to negate the contention that there is a direct relationship between open shelf-life dating and the actual freshness of food,” the study found.

There’s no way to “accurately determine dates for various products, no consensus on which type of date or dates … to use for which product, or even which products to date at all, and no real guidelines as to how to display the date,” the report’s authors wrote.

Decades later, we’re still in the same boat. “There are no uniform or universally accepted descriptions used on food labels for open dating in the United States,” according to the USDA’s current guidance.

The FDA said that manufacturers can’t place false or misleading information on labels, but that “they are not required to obtain agency approval of the voluntary quality-based date labels they use or specify how they arrived at the date they’ve applied.” Carothers, from the FSIS, reiterated that dates can be applied as long as they don’t mislead customers and comply with the service’s labeling regulations.

Where we go next: The sniff test

To avoid food waste, some advocates encourage people to rely on their senses when determining whether certain foods are safe to eat.

The British retailer Morrisons said early this year that it is removing “sell by” dates from some of its branded milk, switching instead to “best before” dates and encouraging customers to decide whether to discard the product based on how it looks and smells.

Morrisons offered these guidelines to consumers: if it looks curdled or smells sour, ditch it. If it looks and smells okay, you can consume it even after the date.

“When food is decayed past the point where we’d want to eat it, our defenses work very well,” said ReFed’s Gunders. “If food doesn’t look good, if it doesn’t smell good, if it doesn’t taste good, if it’s slimy … then absolutely, we should not eat that food.”

In general, Gunders recommended that those who are concerned about food safety remain strict about consuming food before the sell-by date if it has a “higher potential to carry listeria.” One way to identify those items? They’re the foods that pregnant women are told to stay away from, she said.

Another way to prevent confusion, experts say, is to regulate the language used to describe these dates.

“Best by” versus “Use by”

The Food Date Labeling Act of 2021, introduced in December of last year, wants manufacturers to use “use by,” or “best if used by” only before dates on labels. The bill is the latest in a series of legislative efforts to make a national labeling standard.

Here’s the logic: Companies that decide to put a date on labels have to make clear to consumers whether the item is potentially unsafe after that date, or if it just tastes a little off. If it’s a safety issue, they have to use “use by.” If it’s about food quality, “best if used by” is the way to go.

Gunders and agencies like the FDA and USDA point to this label harmonization as a good solution. Many companies have already made the transition.

Del Monte, which sells canned fruits and vegetables among other products, uses “best if used by.” In an email, the company explained that the dates “are a guideline.” Dole, which has dates on its packaged salads, also uses the “best if used by” label.

Even if the bill becomes law and all companies make the same changes, there will still be a missing piece of the puzzle: Alerting consumers to the shift and what it means.

After all, consumers who pick up an item today won’t necessarily know that “use by” is distinct from “best if used by,” or if either of those are different from something like “enjoy by,” or “sell by.”

To make the dates clearer to the public, there needs to be a “consistent and engaged effort to help consumers think through this,” said FMI’s Harig. “I think it’s going to take some work to figure it out.”