Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on June 23, 2022. It has been updated to reflect recent developments.

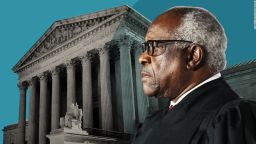

While Justice Clarence Thomas spent 63 pages in a 6-3 majority opinion Thursday painstakingly explaining the court’s reasons for striking down a New York conceal carry gun law and changing the way judges will analyze a host of other gun regulations going forward, his colleague Samuel Alito took a different tack.

In a sparse but relentlessly caustic concurring opinion, the conservative Alito criticized his liberal colleagues for their dissent, blasting them for attempting to “obscure” the specific question the court had decided, and for referencing the recent mass shootings that have shocked the nation.

The fact that Alito, who joined Thomas’ opinion in full, chose to also strike out alone against the dissenters highlights the current tension on the court triggered by a blockbuster docket and the unprecedented leak of a draft majority opinion in May overturning Roe v. Wade.

Alito authored that draft opinion, and Friday’s bombshell ruling triggered an angry dissent from the court’s liberal justices.

But already, the liberals and conservatives have openly sparred in opinions. On Tuesday, for instance, Justice Sonia Sotomayor ended one dissent in a religious liberty case that broke down along ideological lines with this warning: “With growing concern for where this Court will lead us next, I respectfully dissent.”

On Thursday it was Alito’s turn – and in a case that he had won.

In his concurrence in the gun case he took on the liberal dissent penned by Justice Stephen Breyer and joined by Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan.

“Much of the dissent seems designed to obscure the specific question that the Court has decided,” Alito complained.

Breyer did begin his dissent with a focus not on the gun law at issue, but gun violence in the country, noting in his first line that in 2020, 45,222 Americans were killed by firearms. For Breyer, the most important part of the majority’s opinion was not how it disposed of the New York law, but in how it changed the framework courts should use going forward in deciding gun cases.

Instead of a focus on a state’s reason for passing the law, the majority said courts should consider whether modern firearms regulations are consistent with the Second Amendment’s text and historical understanding.

Breyer said such an approach would hurt state efforts in a broader context and referenced the fact that since the start of the year there have been 277 reported mass shootings.

“Many States have tried to address some of the dangers of gun violence just described by passing laws that limit, in various ways, who may purchase, carry or use firearms of different kinds,” Breyer said. “The Court today severely burdens States’ efforts to do so.”

Alito, in his concurrence, seemed at first to ignore the framework issue and contend that the only thing the majority had really done was strike down the New York law.

“That is all we decide,” Alito wrote. “Our holding decides nothing about who may lawfully possess a firearm or the requirements that must be met to buy a gun.”

Turning to Breyer, Alito wrote that “it is hard to see what legitimate purpose can possibly be served by. most of the dissent’s lengthy introductory section.”

“Why, for example, does the dissent think it is relevant to recount the mass shootings that have occurred in recent years?” Alito asked.

But critics say Alito was cherry picking from the majority opinion, arguing that the court’s new test will apply to all gun laws down the road.

“Justice Alito is ignoring the fact that in addition to striking down New York’s law the Court is announcing a new standard for Second Amendment cases unlike anything the court has ever applied before,” said Jonathan Lowy, chief counsel at Brady. He said the new standard is going to apply to “every sort of gun law going forward.”

For Alito, the New York conceal carry law in front of the court had an attenuated relationship with the mass shootings.

“Does the dissent think that laws like New York’s prevent or deter such atrocities?” he asked.

“How does the dissent account for the fact that one of the mass shootings near the top of its list took place in Buffalo? The New York law at issue in this case obviously did not stop the perpetrator,” Alito said.

He also took Breyer to task for using statistics about the use of guns during suicide.

“Does the dissent think that a lot of people who possess guns in their homes will be stopped or deterred from shooting themselves if they cannot lawfully take them outside,” he asked.

And Alito criticized Breyer for citing statistics on children and adolescents killed by guns.

“What does this have to do with the question whether an adult who is licensed to possess a handgun may be prohibited from carrying it outside the home?” he asked.

“Our decision, as noted does not expand the categories of people who may lawfully possess a gun and federal law generally forbids the possession of a handgun by a person who is under the age of 18,” he said.

The George W. Bush-appointee finally turned to a point he made at oral arguments – the fears of law-abiding citizens who want to protect themselves. He said that the dissent failed to understand those fears.

“Some of these people reasonably believe that unless they can brandish or, if necessary, use a handgun in the face of attack, they may be murdered, raped, or suffer some other serious injury,” he said.

He said the “real thrust of the dissent” was that “guns are bad.”

Breyer – in writing what may be one of his last big dissents before retirement – struck back.

“I am not simply saying that ‘guns are bad,’” he said.

But he said that balancing “lawful uses” against the “dangers of firearms” is primarily the responsibility of elected bodies such as legislatures.

“Justice Alito asks why I have begun my opinion by reviewing some of the dangers and challenges posed by gun violence,” he said.

Breyer said he did so because the “question of firearm regulation presents a complex problem – one that should be solved by legislatures and not courts.”