When Dr. Nesli Basgoz met her patient for the first time in May, he had been admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital with symptoms that were quite common for many infectious diseases – fever, rash, fatigue, sweats.

Basgoz and her colleagues at the hospital tested the patient for chickenpox. He was negative. They tested him for syphilis. He was negative.

The doctors still treated him with antibiotics and antivirals that are used for common infections while they waited for his various test results – but his condition did not improve in response to those treatments.

As days progressed, Basgoz noticed that the patient’s rash changed in appearance. At that moment, she knew he did not have a common illness.

Her mind raced, putting together pieces of a medical puzzle.

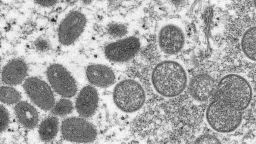

“Some of the skin lesions, called the pustules, started to have indentations in them, and that’s a feature that can be seen in pox viruses,” Basgoz, the hospital’s associate chief and clinical director of the infectious disease division, told CNN.

“The combination of not improving when he was treated for common things; the results of testing for common infections coming back negative; and some change in the appearance of the rash – all sort of raised the possibility that this could be a pox virus,” she said. That was her ah-ha moment.

The patient, whom Basgoz described as “a relatively young and healthy man,” had traveled to Canada before becoming the first person to be confirmed with monkeypox in the United States this year as part of an ongoing global outbreak. So far in the outbreak, global health officials have identified more than 1,200 patients across at least 31 countries, as of Friday.

Why symptoms in current outbreak appear more subtle

Monkeypox “wasn’t initially on our radar screen,” Basgoz said about treating the first US case.

As the monkeypox virus spreads, some doctors and public health officials have noticed that patients are presenting with milder symptoms that could be mistaken for other illnesses. Two factors could help explain why the disease sometimes presents in more subtle ways, Basgoz said.

“One major reason is that the main strain associated with this outbreak is the West African clade, and that’s associated with milder disease,” Basgoz said, compared with the other, which is the Central African clade.

“The second is so far, of the patients who are reported, there are a large number of relatively young and otherwise healthy persons,” Basgoz said. “When you see an infection in relatively young and otherwise healthy people, it is often milder than when you see it in people who are older or who have other medical conditions.”

Monkeypox spreads through direct contact with body fluids or sores on the body of someone who has been infected, or through direct contact with materials that have touched body fluids or sores, such as bed sheets or clothing, according to the CDC.

The spread of monkeypox through small virus particles that linger in the air “has not been reported,” the CDC said in guidance posted Thursday. It may spread through “saliva or respiratory secretions” during face-to-face contact, but these secretions “drop out of the air quickly,” and this method of transmission seems uncommon.

The CDC has said that the risk to the general public remains low, but health care providers should be alert for patients who have rash or illness consistent with monkeypox.

“Historically, people with monkeypox report flu-like symptoms, such as fever, body aches and swollen glands, before a characteristic often diffused rash appears on multiple sites of the body, often on the face, arms and hands. But during the current outbreak, some patients have developed a localized rash, often around the genitals or anus, before they experienced any flu-like symptoms at all, and some have not even developed such flu-like symptoms,” CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said in a news briefing Friday.

She added that for some patients, the rash doesn’t always extend beyond its initial site to other parts of the body, or might appear on only a few sites of the body.

“This could look like a whole lot of different things – the fevers, chills, body aches, headaches that we’ve talked about with Covid-19 also can occur as the prodrome, the first signs or symptoms, of monkeypox,” Dr. Christina Wojewada, chair of the College of American Pathologists’ microbiology committee and director of clinical microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center, who was not involved in the CDC’s guidance, told CNN.

“The lesions themselves can get confused with the lesions of herpes or chickenpox, or syphilis, and so sexually transmitted disease clinics might be seeing more of these patients for that, because they can present similarly to those diseases,” Wojewada said. “So, I think it’s important both for patients and clinicians to give a full history of your potential exposures so that, if appropriate, testing for monkeypox can be performed.”

Increased monkeypox testing needed

The 45 monkeypox patients who have been identified in the United States so far are located across 15 states and Washington, DC, and the virus does not seem to be spreading in “one particular area” of the country, a CDC official said in Friday’s news briefing.

“We don’t have an area identified right now in the United States that seems to be having an urban outbreak, like what has been reported for Montreal and some other places. We don’t have one area where it looks like there’s a lot of community transmission happening,” Dr. Jennifer McQuiston, a veterinarian and deputy director of the CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said in the briefing.

Most cases in the United States – 75% or more – are still reporting that they may have been exposed to the virus during international travel, McQuiston said. Some other patients have reported contact with a known monkeypox case, and they were identified through contact tracing.

But there are also some patients who are not sure how they acquired monkeypox, “and that might suggest that there is some community transmission happening at levels that are below what’s coming to the attention of public health officials,” McQuiston said.

“There are just these occasional sparse cases that are not sure how they acquired monkeypox,” she added. “In all likelihood, they acquired it from someone who recently traveled but they’re just not sure – and that’s the situation we’re in in the US right now. This could change. We could start to have community spread, and I think that we need to make sure our testing is increasing and that we’re able to catch it when it happens.”

CDC researchers and health officials published a report last week describing how among 17 cases described in the report across nine states, all experienced rash as a sign of illness and most of the cases have been diagnosed in men who identify as gay, bisexual or men who have sex with men (MSM).

“The high proportion of initial cases diagnosed in this outbreak in persons who identify as gay, bisexual, or other MSM, might simply reflect an early introduction of monkeypox into interconnected social networks; this finding might also reflect ascertainment bias because of strong, established relationships between some MSM and clinical providers with robust STI services and broad knowledge of infectious diseases, including uncommon conditions,” CDC researchers wrote in the report.

“However, infections are often not confined to certain geographies or population groups; because close physical contact with infected persons can spread monkeypox, any person, irrespective of gender or sexual orientation, can acquire and spread monkeypox.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Basgoz, of Massachusetts General Hospital, hopes that while people are aware of what monkeypox symptoms can look like in this outbreak – they understand the risk is low and do not stigmatize the disease.

After all, viruses are all around us, she said, and trillions of microorganisms even live in our bodies without us realizing it, with viruses outnumbering bacteria.

“They’re everywhere,” Basgoz said. “Most of them don’t make us ill, but occasionally they do, and so, I really like to put this in context for people.”

CNN’s Michael Nedelman contributed to this report.