A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here

Perhaps the most striking element of CNN’s new film, “Navalny” – which is available now on CNNgo and HBO Max and is about the Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny – is his decision to return to Russia, after his poisoning, to face prison or death.

While Navalny is facing years in a Russian penal colony and only sporadically able to communicate with the outside world, his chief of staff and others carry on his work, largely with posts to YouTube.

I talked to Maria Pevchikh, head of investigationsfor Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, about how the work continues, whether it’s seen in Russia and why the word “politician” has a very different meaning there.

Excerpts of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

‘Politician’ means something different for Russians

WHAT MATTERS: One remarkable thing is Navalny’s willingness to sacrifice his freedom and safety to return to Russia. That is something that is so foreign, I think, to so many Americans. How do you explain that willingness to give himself up to Westerners who live in more open societies?

PEVCHIKH: Well, “politician” means very different things in the Western world than in Russia …

The American politicians that we see in the movies or in the culture or just the real ones, actually … sometimes these people sacrifice big corporate careers in order to become to become politicians, to run for Congress or to become a member of parliament. So that’s the Western understanding of “politician,” a person who maybe has made a career choice.

Whereas in Russia, a politician is like a warrior and a fighter and a person who has absolutely no perception of risk or threats and all of that …

If you want to call yourself a politician in Russia, you can be poisoned with a chemical weapon.

If you want to be a politician in Russia, you can be shot on the bridge right outside the Kremlin, like (Boris) Nemtsov was in 2015.

If you want to be a politician in Russia, you need to be prepared to go to prison, spend your time there. You need to be prepared for your family being arrested and sent to jail just because of what you do …

This is the price of calling yourself a politician in Russia. And Alexey is exactly like that …

He knew perfectly what was going to happen to him when he landed in Moscow … that he would be arrested. It was a conscious decision, a conscious choice that he made in order to stand by the principles that he is committed to, in order to stand by the words that he was saying to the people as a politician, in order to lead by example.

So I think, I don’t know, it’s a language issue – and it’s two different words for “politician” in the Western understanding and the Russian understanding.

And the Western audience, whoever watches this film, will just have to accept that this breed of politician exists.

How is Navalny’s work continuing while he’s in prison?

WHAT MATTERS: With Navalny in prison, tell us how his fight is being carried on.

PEVCHIKH: We continue to work as hard, probably harder than we worked when he was around, just to show a very clear message that imprisoning Alexey is not going to solve the problem. You can take him away from us, but it doesn’t mean that our anti-corruption work will stop.

So we’re probably doing more than we did before the imprisonment, and that applies to the … anti-corruption investigations that we do.

And that also applies to our YouTube work. We have just launched a new YouTube channel with news on the situation in Ukraine, mainly, and it already got over a million new subscribers in like six or seven weeks.

So we are trying to not only continue what we were doing when Alexey was around, but also kind of broaden the scope of our work.

Where is the Russian protest movement now?

WHAT MATTERS: Watching the film, I was impressed by the large numbers of people who show up in the streets and at the airport to back Navalny. Are his backers the same people we have read about protesting the war in Ukraine

PEVCHIKH: I would imagine that it’s pretty much the same people. It’s those people who are probably the bravest people in the country who are willing to risk their own freedom for a bigger cause, for something meaningful.

The story has changed a lot, because you’ve seen the huge crowds in the film and that was probably the last mass protest we saw in Russia. And these protests were violently dealt with.

All those people that you’ve seen in the movie, they ended up spending 15, 20, 30 days in detention centers. And those people who organize those protests, like my colleagues, some of them ended up spending a year under house arrest for this.

The situation has changed. I’m sure that now the same amount of people still support the anti-war movement. But I don’t think that we see them in the streets anymore, because now it’s no longer just 15 days in the detention center.

Now you’re risking 15 years in prison for your anti-war activity. This is the new law. The risks for everybody who’s willing to protest in the street has increased dramatically, but they still do that.

You see from Russia when some extremely brave people – by themselves, just on their own – they go into the square and just stand there with a poster. So it’s still there. It’s very frightening and it’s very scary for people to protest right now.

How can the opposition grow in a repressive regime?

WHAT MATTERS: Navalny is in prison. We saw this week another politician who was poisoned, Vladimir Kara-Murza, returned to Russia only to be arrested after talking on CNN. How can the opposition movement communicate and grow in these conditions?

PEVCHIKH: Well, I don’t think there is a recipe for that. The Russian opposition needs to grow and exist despite everything. I think this is a crisis situation, when whoever has any energy and power and convictions left – you just have to kind of scramble everything together and do at least something every day …

I don’t think that at this time of all the volatility (Russian President Vladimir)Putin will allow for any type of grassroots protesting to emerge. But that doesn’t cancel the fact that we just have to plow through this darkest time in the best way that we can.

And each of us, whoever considers him or herself in opposition, needs to invest this little bit every day like a little drop in the ocean that theoretically one day should convert into these big, collective efforts. So that is going to put an end to this nightmare.

How is the message getting through to Russians?

WHAT MATTERS: The independent media has essentially shut down in Russia, where protesters are being arrested. It’s hard for us in the West to know what’s going on there. Are you able to talk to people in Russia? What do they tell you about life right now?

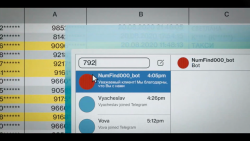

PEVCHIKH: (Here she explains that the Anti-Corruption Foundation sped up plans to launch a political YouTube channel and now broadcasts nightly streams on Ukraine that are available in Russia with a virtual private network, or VPN, connection.) There is definitely a market left behind by those independent media outlets that were shut down. And we’re trying to fill this void.

And even those media channels that have been shut down, they are now kind of reassembling a little bit, and I can see them starting their new media outlets from abroad.

So I don’t think that it’s possible to just shut down independent information completely. Those who look for it, they will find it …

One of the biggest goals that we have when it comes to (this)work is to break through this wall of propaganda … hoping that every day there is someone new watching our show, and that someone new will probably bring tomorrow a friend or two who will also join and watch it – and that will just eventually snowball into something important.