Labor unions haven’t had this much success in decades.

After years of failed organizing efforts and a long, steady decline in the number of private sector workers represented by unions, two grassroots upstart groups have scored recent victories at two of the nation’s largest employers: Amazon and Starbucks.

Both efforts represent only a tiny fraction of those companies’ total employees. But they also represent a sea change in the mainstream conversation about American labor — and they could inspire more union efforts.

“I think it’s very significant, even though it’s a small percentage of the workforces so far,” said Alexander Colvin, dean of Cornell University’s Industrial and Labor Relations School. “I do think that’s a real shift we’re seeing.”

The National Labor Relations Board reports that from October 2021 through last month, 1,174 petitions were filed at the agency seeking union representation.That’s up 57% from the same period a year earlier — and the highest level of union organizing in 10 years.

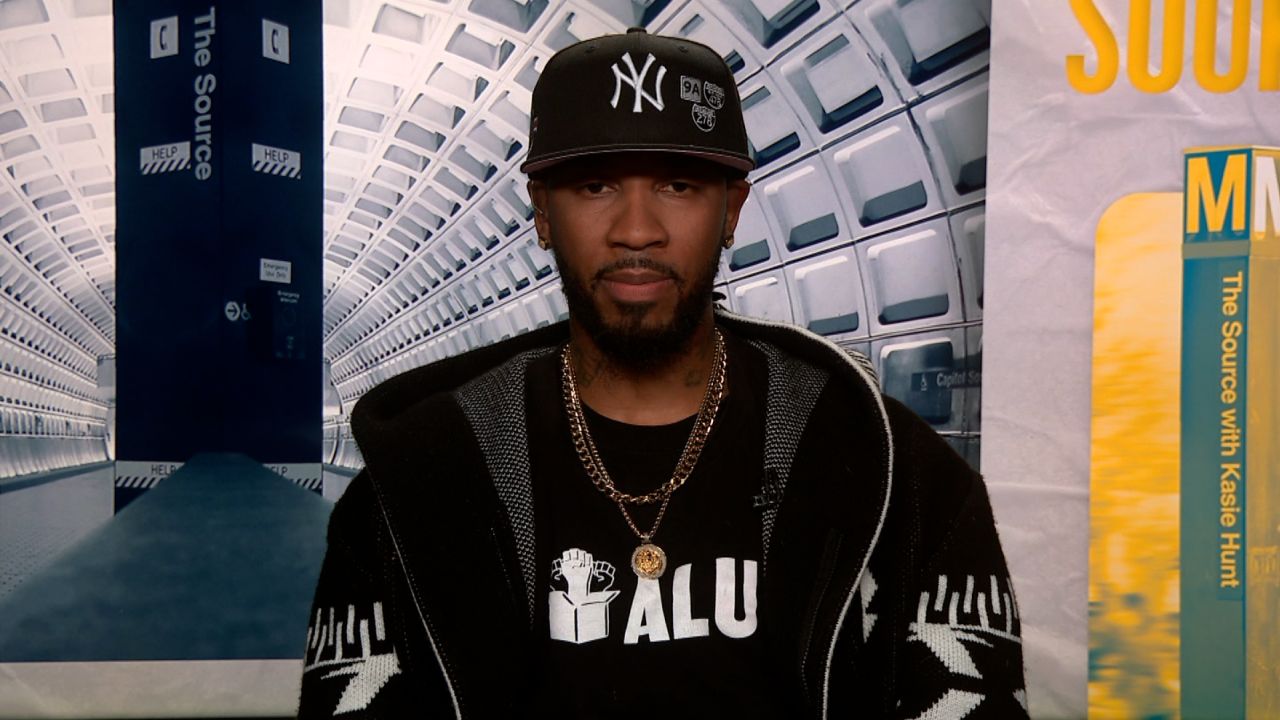

The Amazon and Starbucks victories are important to union organizing efforts, Colvin said. That sentiment is echoed by Chris Smalls, who went from fired Amazon employee to the the leader of the Amazon Labor Union, which recently became the first union to win a representation vote at one of Amazon’s facilities.

Since that vote at Amazon’s Staten Island, New York, facility where Smalls used to work, he has talked to workers at 50 other Amazon facilities nationwide who want to hold their own union votes. Another vote is scheduled for later this month at a different Staten Island Amazon facility.

“I think what we did … is a catalyst for a revolution with Amazon workers, just like the Starbucks unionizing effort,” he said on an interview on CNN+ last week. “We want to have the same domino effect.”

Domino effect

Over at Starbucks, since December workers at 17 stores from Boston to its hometown of Seattle have voted to be represented by Starbucks Workers United — a separate grassroots union effort that has filed to hold votes at more than 100 additional stores.

Starbucks has about 235,000 workers spread across 9,000 company-operated US stores. Fewer than 1,000 workers at the 17 stores have voted for the union. It’s similar at Amazon, where some 8,300 hourly workers were eligible to vote at the Staten Island facility. That’s not even 1% of the company’s US workforce of 1.1 million employees, including both warehouse and office workers.

But the votes have grabbed headlines, and the Labor Board figures suggest the efforts Amazon (AMZN) and Starbucks (SBUX) may be inspiring others.

Union leaders talk of wanting not just better pay and benefits, also but improved job security, staffing levels and workplace safety measures — as well as better working conditions overall and a voice in how workers are treated. Employers generally tend to argue workers are better off with no “third party” standing between workers and management.

“While not all the partners supporting unionization are colluding with outside union forces, the critical point is that I do not believe conflict, division and dissension – which has been a focus of union organizing – benefits Starbucks or our partners,” said CEO Howard Schultz in a message to the company’s employees, who are referred to as “partners,” shortly after reassuming the CEO position at the company.

Still, the efforts seem to be having an effect. Starbucks recently announced it suspended repurchases of its stock, a move that would benefit primarily its shareholders, in order to invest more in its employees. The company also instituted two wage increases in the last 18 months, and in October said it would raise wages to at least $15 an hour for baristas, with most hourly employees earning an average of nearly $17 an hour by this summer.

Many of the unions’ demands stem from the difficulties of working during the pandemic during the last two years, said John Logan, professor of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University.

Covid-era changes

“Part of what’s changed is we’re just in a different moment, [with] frontline workers feeling they were not rewarded or treated with respect during the pandemic,” said Logan. “I think something has really changed in the consciousness of young workers.”

The very tight labor market — with more job openings than there are job seekers and a record number of workers quitting — is making it easier to organize today, said Colvin. While workers don’t want to lose a job at the company they’re trying to organize, the fact that other jobs are available can make them more willing to take that risk.

A more union-friendly NLRB under the Biden administration is also a factor. Amazon appealed the vote at the Staten Island facility, alleging the labor board acted “unfairly and inappropriately” and delayed investigating what it calls “frivolous” unfair labor practice charges.

In a statement Kayla Blado, the NLRB’s press secretary, said the board “is an independent federal agency that Congress has charged with enforcing the National Labor Relations Act,” and its enforcement actions against Amazon are “consistent with that.”

“Things are changing for the better for workers. They’ve implemented remedies that make easier to organize,” said Amazon Labor Union president Smalls. “We still have a long way to go.”

Perhaps the biggest potential change under the new, more labor-friendly NRLB is a recent opinion by its general counsel that management should no longer be able to require workers to sit through presentations about the company’s union stance, arguing that doing so violates workers’ right to refrain from organizing-related activities. Such meetings are central to management efforts to defeat union organizing efforts.

Smalls called the compulsory meetings one of the biggest challenges the union faced. “They have 24-hour access to the workers. You can’t compare and compete with that,” he said.

The opinion doesn’t change current law, which allows for those meetings, although Colvin said it wouldn’t surprise him if the Democrat-controlled NLRB votes to change it. From there, it’s a likely court battle that could go all the way to the US Supreme Court, which has already indicated it is far less supportive of unions.

Decline in union membership

Even with the recent wins for unions, there are numerous long-term trends still in place that have reduced union membership to only 7% of private sector employees over the last 50 years. A main reason is the shift from manufacturing to service-sector jobs like those at Starbucks and Amazon, said Colvin.

Other factors contributing to declining union membership include the rise of nonunion competitors, automation, the building of facilities in less union-friendly Southern states and shifting production overseas.

Finding ways to organize at Amazon and Starbucks and other service sector companies in fields like technology, finance and retail is a key to turning around those long-term trends, experts say.

It’s an uphill battle for unions to win new members, but that doesn’t mean they can’t succeed, said Erik Loomis, a labor historian and associate professor at the University of Rhode Island.

“Amazon is the GM or the US Steel of our time — and it took decades to organize those places,” he said last month, before the vote results at Amazon were known. “It took many different forms of campaigns led by different ideologies, different modes of organizing … before these kind of companies were finally successfully organized.”