Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

For years, researchers have sought to understand why Vikings abandoned one of their settlements in Greenland after centuries of success. While some experts have suggested that dropping temperatures may have been the cause, new research suggests the cold wasn’t a factor.

Instead, the Vikings faced a new adversary they couldn’t defeat: drought.

A study detailing the findings published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The colder temperature hypothesis has persisted for years because of something called the Little Ice Age that occurred between 1300 and 1850, when cooling temperatures persisted in the North Atlantic region.

The Vikings established their settlement, known as the Eastern Settlement, in southern Greenland in 985. They cleared out shrubs and planted grass for their livestock to graze. The settlement grew to hold around 2,000 Norse.

The settlement was abandoned by the early 1400s. The exceptionally cold weather brought on by the Little Ice Age, which was not a true ice age because it didn’t happen globally, made the Norse agricultural and farming life unsustainable, scientists believed.

But there was no actual evidence to support this reasoning for why the Vikings cleared out. Ice cores used in previous research to show Greenland’s historical temperature range were collected from more than 621 miles (1,000 kilometers) away and 6,561 feet (2,000 meters) higher in elevation.

“Before this study, there was no data from the actual site of the Viking settlements. And that’s a problem,” said study coauthor Raymond Bradley, distinguished professor of geosciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in a statement. “We wanted to study how climate had varied close to the Norse farms themselves.”

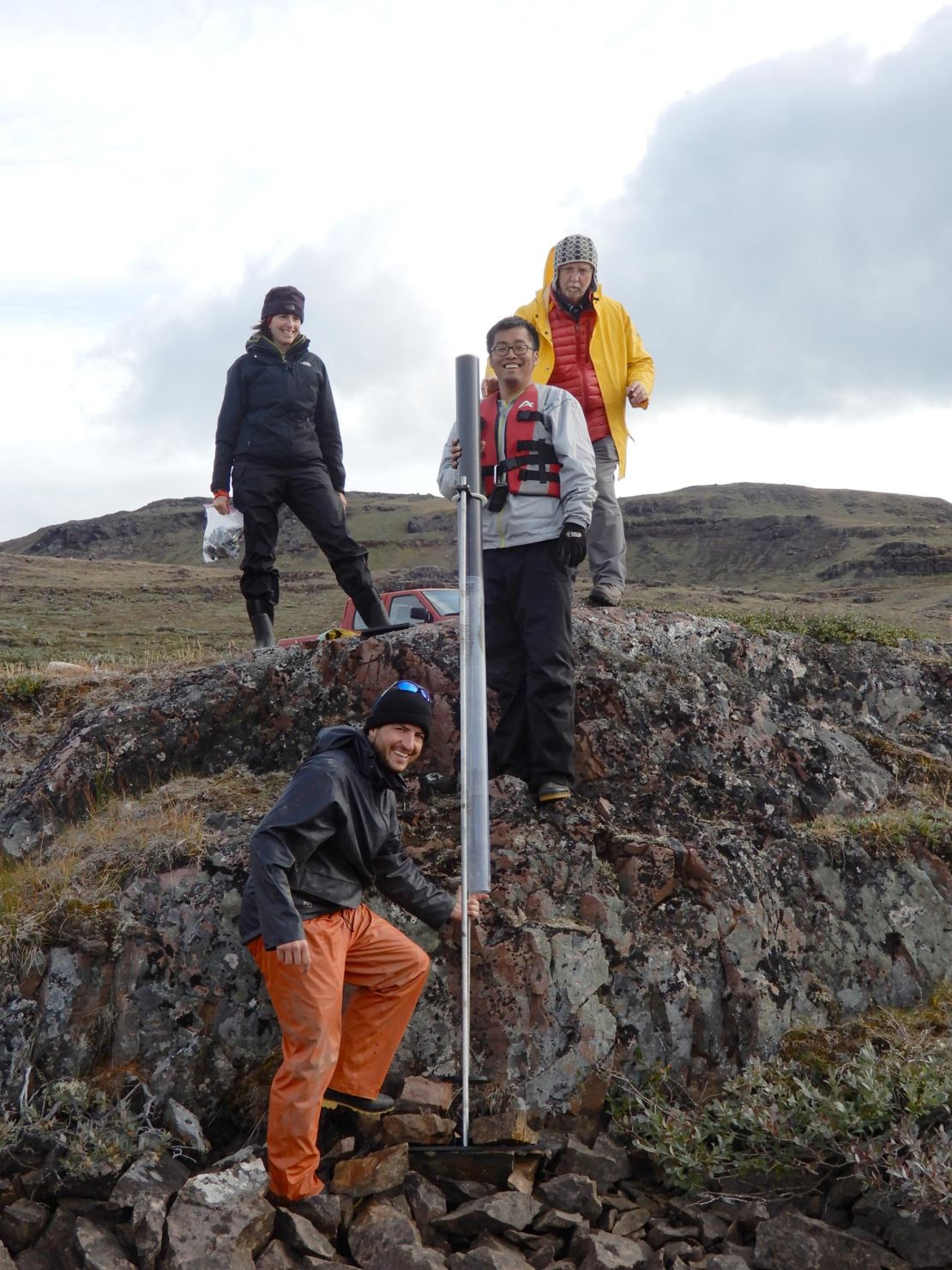

Bradley and the research team set out for Lake 578, which was once close to one of the largest groupings of farms in the Eastern Settlement. It’s also adjacent to a former Norse farm.

For the next three years, the team collected sediment samples from the lake to construct a climate record representing the past 2,000 years.

“Nobody has actually studied this location before,” said lead study author Boyang Zhao, a postdoctoral research associate at Brown University in Rhode Island, in a statement. Zhao conducted the research for his doctorate in geosciences while at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The lake samples were analyzed for elements that could help the researchers reconstruct what the climate and environment were like when the Vikings lived at the settlement. One was a lipid, or an organic compound, called BrGDGT. Produced by bacteria, branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers can be used to identify historic temperatures.

“If you have a complete enough record, you can directly link the changing structures of the lipids to changing temperature,” said study coauthor Isla Castañeda, professor of geosciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in a statement.

The second element came from a waxy coating on plant leaves, which helped the researchers determine how much water was lost by grass and other plants through evaporation. This coating can be used to tell how dry it was when the plants were growing.

“What we discovered is that, while the temperature barely changed over the course of the Norse settlement of southern Greenland, it became steadily drier over time,” Zhao said.

The drier climate trend continued and peaked in the 1500s. Drought can reduce the growth of grass, which is a crucial food source for livestock to get through the winter.

Norse settlers had already experienced farming and raising livestock in other challenging environments, like Iceland and Norway, before they landed in Greenland.

During the winter, Norse farmers would keep their livestock in warm sheds along with stored fodder, like dried grass. By the spring, the cattle were usually too weak to move, so the Vikings would actually carry them back out to the pasture once the snow melted.

These were common practices during times without environmental or climate stressors, so an extended drought along with any other economic and social pressures could have turned the Eastern Settlement into a place the Vikings wished to abandon.

The researchers also found evidence that the diet of the Vikings changed over time, turning from livestock to marine food sources. This forced the Norse to “hunt sea mammals, which was a more dangerous and uncertain activity,” according to the study authors.

There was also an increase of sea ice, which likely made fishing and marine hunting even more difficult.

Drought still occurs during the summer in southern Greenland today. Now, farmers can just import hay, but that wasn’t an option for the Vikings.

The study authors hope their research not only shifts our understanding of the Vikings, but how climate and environment have and continue to impact our lives.