Editor’s Note: Nikos Tsafos is the James R. Schlesinger Chair in Energy and Geopolitics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own.

In a matter of weeks, the war in Ukraine has upended an energy relationship between Europe and Russia that goes back decades. Europe understands that it cannot sever ties with Russia overnight, as it still needs Russian energy. But Russia’s role in the European and global energy system has been shaken. This is a profound shift that will mark the end of Russia as an energy superpower.

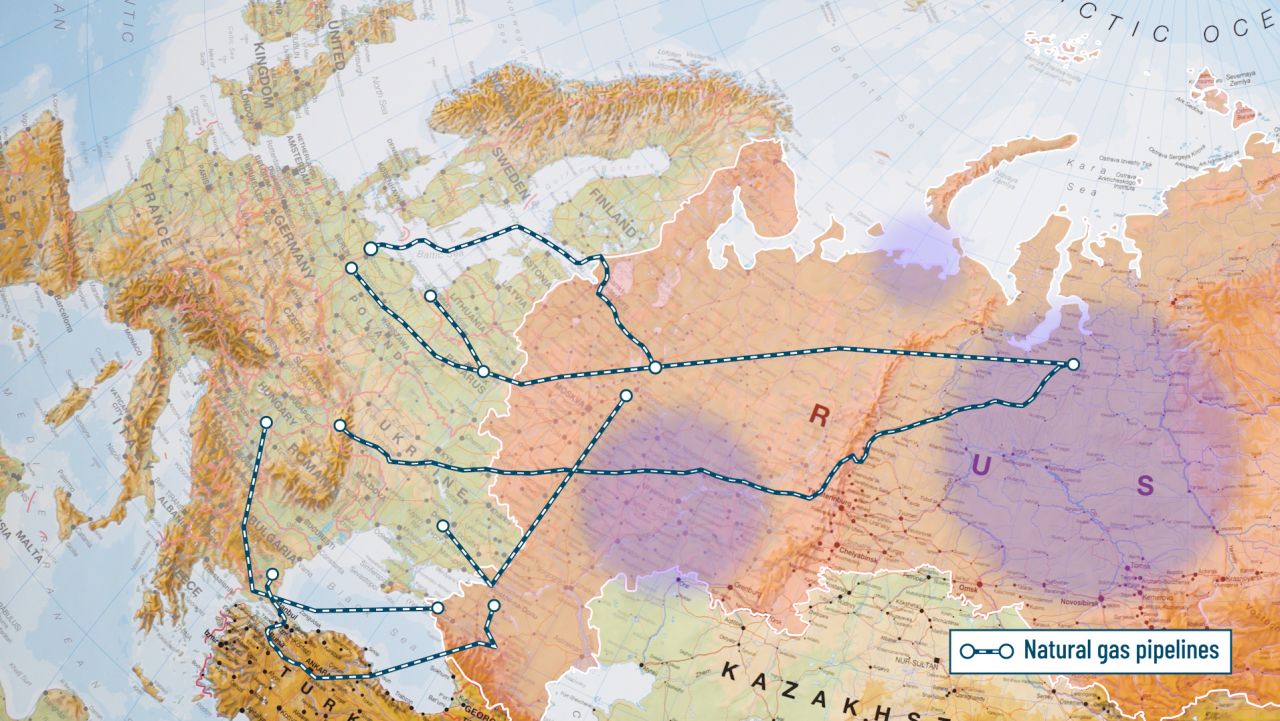

Russia is central to the global energy system. It is the world’s largest exporter of oil, making up about 8% of the global market. And it supplies Europe with 45% of its natural gas, 45% of its coal and 25% of its oil. Likewise, hydrocarbons are the lifeline of Russia’s economy. In 2019, before Covid-19 depressed prices, revenues from oil and natural gas accounted for 40% of the country’s federal budget. And oil and gas accounted for almost half of Russia’s total goods exports in 2021. It is hard to imagine what the Russian economy looks like without oil and gas.

Since the invasion, Europe has been scrambling to come up with a new energy security strategy. Most European countries had assumed that the dependence on Russian energy was a risk they could manage, uncomfortable as it was at times. They believed that Russia was a rational actor that wanted to earn money selling its energy. But the largest land war in Europe in generations has produced a rapid reassessment of those assumptions. Europe was accustomed to dealing with an adversary; now it must deal with an enemy.

To be sure, the European response has been swift. Europe outlined an ambitious plan to cut Russian gas imports by two-thirds in 2022, with a goal to phase out Russian oil and gas by 2027. European leaders are meanwhile debating proposals for an immediate ban on Russian oil imports. The United Kingdom already said it would eliminate imports of Russian oil by the end of 2022. Germany halted approval for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline and said it would invest in infrastructure to import liquefied natural gas (LNG). A new import facility for LNG is now being built in the Netherlands. The turn away from Russia is happening fast.

Major energy companies like Shell, ExxonMobil and Equinor are walking away from investments that go back decades. Public opinion is constraining their willingness to buy Russian oil on the open market, which is shrinking Russia’s footprint on the energy stage.

But Europe is now in a tough spot. Russian oil and gas is indispensable. But relying on Russia is no longer tolerable given Russia’s atrocities in Ukraine and the fear that it might shut off gas supplies at any moment. So Europe wants out of the relationship.

These opposing forces create a gap between where Europe is and where it wants to be. How this is resolved in the next few years is unclear given that alternative supplies are limited in the short term. For now, the European Commission has called on companies to secure supplies from countries like the United States, Qatar and Egypt, a move that could cause prices to rise further as demand pushes up against limited supply. But what comes after this adjustment period is clear enough: Europe’s energy trade with Russia will eventually dwindle to near zero.

Russia will turn elsewhere for customers. Around 20% of Russia’s oil heads to China, and its natural gas sales there are sure to rise, courtesy of a pipeline that runs more than 8,100 kilometers. But Russia’s turn to the East is limited by geology, geography and geopolitics. Russia has more oil and gas resources in West Siberia than in the East, making it harder to serve Asia. The existing infrastructure is also set up to send energy to Europe. China’s willingness to finance a shift of this magnitude — re-wiring Russia’s export infrastructure to head East — is unclear. Will China take a bargain deal if it is offered? Probably. Will it choose to depend heavily on Russian energy? Probably not.

A decade from now, these dynamics will change Russia’s position in global energy and the world economy. Russia will not be cut out from the global energy market completely, but its role will shrink considerably. This war has done irreparable damage to Russia’s brand as an energy provider.

Some strategists argue that Russia’s capacity to wage war will be diminished without the fossil fuel revenues to fund its military. This is true — to an extent. But Russia has been involved in European affairs for centuries. Russia’s aggression, insecurity and meddling in Europe will persist long after the hydrocarbon era. After all, a Russian economy that is isolated from global markets is unlikely to be a pliant neighbor. The war will accelerate the end of the era where Russia is an energy superpower. But whether the new Russia is any better — that is impossible to know.