In a year when all Xi Jinping craved was for things to be stable, 2022 is shaping up to be anything but.

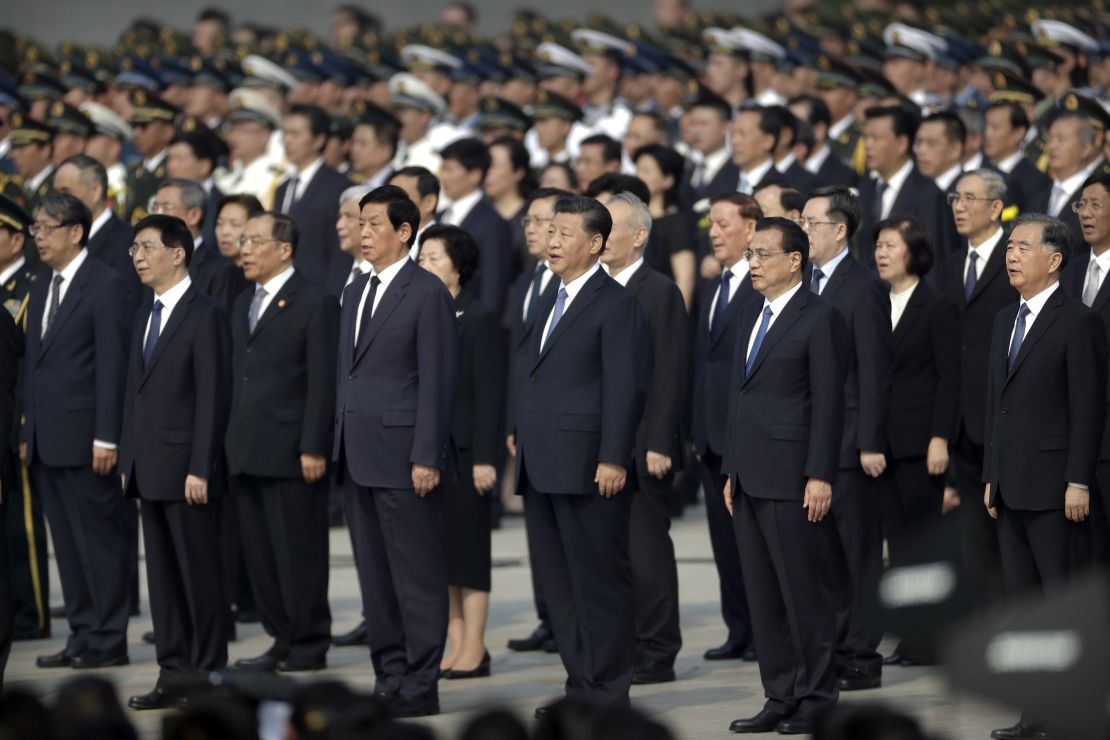

After years of careful preparation, the Chinese leader is expected to step into an almost unprecedented third term at the helm of the country and its Communist Party this fall.

But instead of a smooth ride, dual crises are threatening to upend the status-quo, with China’s largest outbreak of Covid-19 in two years emerging at home while overseas, Russia embarks on a brutal, widely denounced invasion of Ukraine.

The war comes just weeks after Beijing declared a limitless partnership with Moscow, putting China’s diplomats on the back foot and pushing China to make an existential choice about its future international role.

While Xi’s path to a third term may not be imperiled by these twin crises, both will need to be navigated carefully as the 68-year-old leader steers the country toward its twice-a-decade leadership reshuffle at the 20th Party Congress this fall.

“From Beijing’s perspective there is no higher priority than stability ahead of the Party Congress – as we all know it’s by no means an election, but this is the closest you might come to seeing a ‘campaign season’ in China,” said Natasha Kassam, director of the Public Opinion and Foreign Policy Program at the Australia-based think tank the Lowy Institute.

“We know that most opposition to Xi has been eliminated … but there is still the expectation of delivering on particular needs for the majority of people,” she said.

That may be especially true for a leader who has spent years consolidating power and oversaw the removal of constitutional term limits on the presidency – paving the way for him to stay on top in the closed-door, elite political process that decides who will lead China for the next five-year term.

In doing so, Xi has placed himself at the center of the party and state in a way not seen since Communist China’s founding father Mao Zedong decades ago – a position from which the country’s successes can rest on his shoulders, but so too can its failures.

Complicated friendship

As Russian tanks, soldiers and fighter planes advanced into Ukraine from multiple sides last month, China appeared to some observers to have either been playing along – or played.

Days before the invasion, Beijing continued to publicly dismiss US intelligence that a Russian assault of its neighbor was imminent, despite Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin earlier that month signing a 5,000-word joint joint statement that included an expression of their shared disapproval of NATO expansion – an issue that’s been key to Putin’s rationale for his assault on Ukraine.

The importance of that meeting – the 38th between the two leaders since 2013 – was only underscored by the fact it was Xi’s first in-person summit with another head of state in nearly two years, as China has maintained stringent control over its border during the Covid-19 pandemic.

While views diverge on how much Xi may have known about Putin’s true plans, as Russia’s unprovoked invasion wears on, China’s position of both saying it respects international norms, while not condemning Russia, is growing increasingly untenable.

“Now this (situation) is impossible for China – China will either have to be in support of global institutions or it will be against them. That’s it,” said Victor Shih, a professor at University of California San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy. “(For China, it’s turned) into a diplomatic and potentially economic headache.”

That risk for China, and by extension Xi, is two-fold: on the one hand, if it violates a raft of stringent sanctions imposed by the West in order to lend support to Russia, Chinese enterprises involved could be hit by secondary sanctions – potentially signing their economic death on the global market.

But more pressing is the risk Beijing’s stance could sink relations between China and its major trading partners in the West. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, these ties were seeing significant strain. Washington and Beijing have been at loggerheads for several years over issues like trade, Taiwan, and China’s human rights record, and there were signs Europe was moving in a similar direction.

Last year, a highly anticipated investment deal between the European Union and Beijing stalled as tensions flared over China’s alleged human rights abuses against Muslim minority groups in its western region of Xinijang.

And when it comes to Ukraine, pressure is already very much on China to choose a side, with US officials saying this week that Moscow has asked Beijing for military aid – a claim both China and Russia deny.

US State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Monday the United States is “watching very closely the extent to which the (People’s Republic of China) provides any form of support, whether that’s material support, whether that’s economic support, whether that’s financial support to Russia.”

On Tuesday, Qin Gang, China’s ambassador to the US, pushed back on “assertions that China knew about, acquiesced to or tacitly supported this war” in an op-ed in the Washington Post, saying instead “had China known about the imminent crisis, we would have tried our best to prevent it” and that Beijing was committed to working for peace.

All this may be making some people in Xi’s China uncomfortable.

“There are certainly differences of opinion (among) Communist Party members and the business community, who are concerned with China being tied to a pariah state and concerned about falling foul of very dramatic sanctions,” Kassam said.

“China’s trade relationship with the world’s democracies is many magnitudes larger than it is with Russia,” she said. Trade between the European Union and China topped $800 billion last year and US-China trade was over $750 billion, according to China’s official data, while its trade with Russia was just under $150 billion.

An example of these differing opinions was on show in a commentary published last week by Shanghai-based scholar Hu Wei, vice-chairman of the Public Policy Research Center of the Counselor’s Office of the State Council, who warned China’s path of not condemning Putin could lead to isolation.

“If China does not take proactive measures to respond, it will encounter further containment from the US and the West,” Hu wrote in a piece published in Chinese and an English translation in the US-China Perception Monitor, a publication of the US-based nonprofit The Carter Center – which said the Monitor’s website was blocked in China not long after the piece was published.

“China should avoid playing both sides in the same boat, give up being neutral, and choose the mainstream position in the world,” Hu said.

But while such concerns may be bubbling under the surface, experts remain skeptical they represent a strong or even dominant view in the Communist Party, given Xi’s own personal embrace of Putin in recent years.

And to move away from Putin would be to risk questioning Xi. “In the short term, (Beijing) cannot change its ‘no limits’ partnership with Russia because it will imply that Xi was wrong to get China into the difficult position in the first place,” said Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Washington-based Stimson Center think tank.

“Xi is aiming for the third term, and this would be a main stain on his record.”

Covid crisis

But looming concerns about whether China’s economy could be impacted by global turmoil sparked by Russia’s war, or any penalties from a further break with Western partners, are coupled with another challenge to stability – both economic and political – on China’s home front.

There, new Covid-19 cases have been reported in the thousands for several days in the largest outbreak in roughly two years. It’s a sharp jolt for a country that has assiduously maintained a “zero-Covid” posture at great cost – shutting its borders to most foreigners since March 2020, rolling out a complex digital tracking system for each individual, and enacting mass testing and snap lockdowns even when a handful of cases were found.

China’s leaders have freely equated that policy, and its relative success at controlling Covid-19, to what they claim is the superiority of the Chinese system over that of Western democracies, where the virus spread rampantly. Such rhetoric has not only played out on Chinese state media – where the horrors of Covid-19 overseas are voraciously covered – it’s also been part of Xi’s own case to the world about why China is an exemplary global leader and force for good.

For more than a year, analysts have suggested China would not relax its stringent zero-Covid policy, even as the rest of the world opens up, until after 2022’s Party Congress was over and Xi cemented his third term – as a widespread outbreak would challenge that carefully cultivated image.

“The last thing that the Chinese leaders want is to have a nationwide, major Covid-19 outbreak that overwhelms the hospitals … and could contribute to social and political instability,” said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“A government failure to effectively respond to such a crisis could translate into a legitimacy crisis (ahead of the Party Congress),” he said.

But now that risk is playing out in real time as authorities around the country race to lock down cities and stamp out cases – with no guarantee these measures will be effective against the newer and highly infectious Omicron variant.

As of Tuesday, five Chinese cities with more than 37 million residents were under various forms of lockdown, and concerns have been growing over the economic fallout from China’s stringent control measures.

At least one major company, Apple supplier Foxconn, suspended operations in Shenzhen, before moving into a “closed loop” system where employees who live on campus can work, as the tech hub went under a soft lockdown after recording 66 Covid-19 cases on Saturday.

A research note from analysts at financial services group Nomura on Friday said the costs of China’s zero-Covid strategy “will rise significantly as its benefits decline,” making it “much harder for Beijing to achieve its “around 5.5%” GDP growth target for 2022” – a figure that was already the country’s lowest official growth target in three decades.

But China’s leaders, and Xi, may be worrying about more than the macro-economic outlook ahead of the Party Congress, according to Lowy Institute’s Kassam. If sustained, widespread lockdowns could strike at the welfare and livelihoods of the more economically vulnerable in the country – groups whose economic security has been part of Xi’s well publicized signature focus through his first two terms as President.

That could see the government more willing to roll out tools to prop up the economy this year than in the past if Covid-19 is not brought under control swiftly, Kassam said.

“Because this one will impact ‘everyman’ first …and if we come back to this idea that we are in ‘campaign season’ – so to speak – that becomes really important.”

While headwinds from these events may have an impact on “everyman,” in China there is one man who is carefully surveying the landscape and pulling the strings.

As these dual crises evolve during a highly sensitive year, experts will be watching closely to see to what extent Xi moves to recalibrate China’s positions both overseas and at home to ensure there are no threats posed to his historic transition into a third term.

Because, as China’s latest government work report – often seen as the Chinese equivalent of the State of the Union address in the US – repeatedly made clear: Xi Jinping is the “core” of the Communist Party leadership. And it is of the highest priority to “maintain overall social stability to welcome the victory of the 20th Party Congress.”