Lia Thomas stood tall and smiled wide atop the championship podium, her nearly 6-foot-4 frame pushing her head past the top of the Ivy League’s green photo backdrop.

With one hand she held a placard reading “Ivy 2022 Champion,” and with the other shestuck up two fingers in that classic sign of victory. Her hair nestled alongside the medal around her neck as a blue University of Pennsylvania jacket hung from her broad swimmer’s shoulders.

Inside Harvard University’s Blodgett Pool, not far from a large banner reading “8 Against Hate,” referring to the Ivy’s eight schools, her victories in the 500-yard freestyle on Thursday, the 200-yard freestyle on Friday and the 100-yard freestyle on Saturday showed a star athlete going about her business. The crowd of family and friends cheered politely, and Thomas posed for photos with Penn teammates and shook the hands of her closest competitors.

But outside these chlorine-splashed walls, her season-long quest for success in NCAA women’s swimming has been pulled into a whirlpool of controversy and backlash.

With each victory, Thomas, a transgender woman who previously swam for Penn’s men’s team, has brought renewed attention to the ongoing debate on trans women’s participation in sports and the balance between inclusion and fair play.

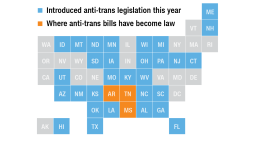

Her face has been prominently featured on Fox News and right-wing news sites critical of society’s changing views on sex and gender. In the past couple of years, Republican-led states across the country have passed laws to keep trans women and girls from participating in girls’ and women’s sports in the name of “fairness,” and Thomas quickly became the personification of those fears. Last week, a Republican Senate candidate in Missouri featured Thomas in a campaign ad and asserted that “Women’s sports are for women, not men pretending to be women,”a transphobic trope belittling trans women.

Yet Thomas’ success has vexed even those who say they support her transition, including some of her fellow swimmers. An anonymous letter purportedly written on behalf of 16 of her 40 Penn teammates earlier this month criticized what they saw as her “unfair advantage,” saying they supported her gender transition out of the pool but not necessarily in it.

Swimming star Michael Phelps, too, expressed his hesitations on the topic in an interview with CNN in January.

“I believe that we all should feel comfortable with who we are in our own skin, but I think sports should all be played on an even playing field,” he said when asked about Thomas. “I don’t know what that looks like in the future. But it’s – it’s – it’s – it’s hard. It’s a really … honestly … I don’t know what to say,” he said, stumbling over his words. “It’s very complicated.”

Phelps is one of many athletes and regulatory bodies struggling to figure out how to include and accommodate transgender athletes in an elite field where tenths of seconds can mean the difference between winning and losing.Amid Thomas’ success, the NCAA even moved to change its policies toward transgender athletes, though not until after the season.

Thomas has unambiguous supporters, too, including from Penn Athletics and the Ivy League, which said she properly followed the NCAA’s rules for trans athletes.

“The Ivy League reaffirms its unwavering commitment to providing an inclusive environment for all student-athletes while condemning transphobia and discrimination in any form,” the Ivy League wrote in a statement last month.

In addition, over 300 current and former swimmers, collegiate and elite, signed their names to an open letter defending her ability to compete. One of her most vocal supporters said there was no room for compromise.

“There isn’t a middle ground,” said Schuyler Bailar, who is a trans man. “You don’t get to slice me in half and be like, ‘Yes, you are a man here but not here,’ or, ‘Yes, Lia is a woman but not here.’ We don’t exist in parts. Our transness is not something we can just take off and put over here. We are whole people.”

Thomas has not spoken publicly since an interview with the SwimSwam podcast in December. In that interview, she nodded in the direction of the controversy but did not engage.

“We expected there would be some measure of pushback by some people. Quite to the extent that it has blown up, we weren’t fully expecting,” she said. “I just don’t engage with it. It’s not healthy for me to read it and engage with it at all, and so I don’t.”

Through an Ivy spokesperson, she and Penn coach Mike Schnur declined to be interviewed for this story, as did several of her closest competitors on other teams.

A swimmer since age 5

Thomas first launched into the public eye with a stunning performance at the Zippy Invitational in Ohio in December.

There, she dominated the women’s field in the 200-yard freestyle, 500-yard freestyle, and 1,650-yard freestyle races, beating the second place finisher by about 7 seconds, 15 seconds and 38 seconds, respectively. Her times in the 200 and the 500 in particular set pool and meet records, qualified her for the NCAA championships, and remain the best women’s time in the nation this season.

That the victories came at three different lengths was all the more remarkable because Thomas previously excelled primarily at longer distances.

The Austin, Texas, native began swimming at 5 years old and was a star athlete long before her gender transition. Thomas arrived to Penn in 2017 and quickly made a mark on the men’s team as a freestyle distance swimmer in the 500-yard, 1,000-yard and 1,650-yard races.

As a freshman, Thomas set a time of 8 minutes and 57.55 seconds in the 1,000-yard freestyle, the 6th-fastest men’s time in the country. Her times in the 500-yard freestyle and the 1,650-yard freestyle were among the top 100 in the country. The next year, Thomas took second place at the 2019 Ivy League championships in the men’s 500-yard, 1,000-yard and 1,650-yard freestyle, shaving seconds off her earlier times.

Yet the improvements in the pool belied internal turmoil. Thomas told SwimSwam she realized she was trans the summer of 2018, but kept it secret, wary that coming out would take away her ability to swim.

“I was struggling, my mental health was not very good. It was a lot of unease, about basically just feeling trapped in my body. It didn’t align,” she said.

She started on hormone replacement therapy in May 2019 and came out as trans that fall, yet she still had to compete on the men’s team. It was awkward and uncomfortable, she said, and her speed suffered as her muscles weakened from the hormone therapy.

At the time, the NCAA required that transgender athletes have one year of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to be cleared to participate. So after a year of HRT, Thomas submitted medical documentation and was approved to compete for the women’s team for the 2020-21 season, she said.

She took the year off of school and competitive swimming due to the pandemic and returned for this season on the women’s team, after about 2 and a half years of HRT.

Despite her success this year, her raw times are significantly slower than they were before her transition. Still, she said she was in a better head space after coming out.

“I’m feeling confident and good in my swimming and in my personal relationships, and transitioning has allowed me to be more confident in all of those aspects in my life where I was struggling a lot before I came out,” she told SwimSwam.

A history of scrutiny in women’s sports

Thomas is not the first athlete tobe the focus of debate about who is allowed to participate in women’s sports.

Since at least the 1930s, the bodies of elite women athletes have been publicly scrutinized, leading athletic bodies like the International Olympic Committee to implement various forms of sex testing to determine if women were eligible to compete. In the 1990s, both the International Association of Athletics Federations and the IOC ended mandatory sex testing but continued to conduct medical evaluations on a case-by-case basis.

Some of these examples have become particularly high-profile. In the 70s there was Renée Richards, the trans ophthalmologist and tennis player who successfully sued to compete in the women’s categoryat the US Open. Competing in her 40s, she rose to become the 20th-best woman tennis player in 1979.

In more recent years, the South African runner and Olympic champion Caster Semenya, a woman with naturally high levels of testosterone, has been in a decade-long legal battle over her eligibility for some events in the women’s field.

Nancy Hogshead-Makar sees eligibility rules as vital to the continued success of women’s sports. The three-time gold medalist swimmer, civil rights lawyer and CEO of the non-profit advocacy group Champion Women has become a spokesperson of sorts for frustrated Penn swimmers and their parents.

Last month she wrote the letter, purportedly on behalf of 16 unnamed Penn swimmers, who said Thomas had an unfair advantage. The identities of the teammates were not revealed, and CNN has not been able to independently verify the number of teammates.

The letter also indicated they believe sex should be considered separately from gender identity during competition.

“We fully support Lia Thomas in her decision to affirm her gender identity and to transition from a man to a woman. Lia has every right to live her life authentically,” the letter says. “However, we also recognize that when it comes to sports competition, that the biology of sex is a separate issue from someone’s gender identity.”

In a phone call with CNN, Hogshead-Makar said it’s important to consider why we have women’s sports in the first place.

“The gap between men’s and women’s athletic performance was so big that if you didn’t give women a special team – their own team – that they would not have opportunities in sports,” she said.

“I want trans people to be loved and accepted and be productive in society and be their true selves,” she added. “I’m talking a small slice of competitive sports.”

‘We express our support for Lia Thomas’

The anonymous teammate letter did not go unanswered. Days later, over 300 current and former NCAA swimmers put their names on a supportive letter in response.

“With this letter, we express our support for Lia Thomas, and all transgender college athletes, who deserve to be able to participate in safe and welcoming athletic environments,” the letter said.

The letter was organized by the organization Athlete Ally and Schuyler Bailar, a former Harvard swimmer who became the first transgender man to compete on a NCAA Division I men’s team in 2015.

Bailar told CNN he organized the message of support because he felt the anonymous open letter was irresponsible and bullying.

“I read that and I cried,” he told CNN on Friday morning at a coffee shop in Somerville, Massachusetts.

When Thomas first decided to come out, she reached out to Bailar on Instagram for guidance about how to move forward with her swimming career, Bailar said. They have remained in contact, though he declined to go into detail on their conversations.

A trans rights activist, Bailar said the outrage against Thomas’ inclusion on the team was not really about questions of sporting fairness.

“It’s not about fairness. It’s about policing women’s bodies,” he said. “It’s about transphobia.”

He pointed out that trans people are actually underrepresented in sports. For all the fear of trans people excelling in women’s sports, there have been only a few Olympians who publicly identify as trans among the tens of thousands of athletes who compete every two years.

How the NCAA deals with transgender athletes

Because there are so few elite trans athletes, there is very little hard data comparing performance between transgender athletes and cisgender athletes.

Indeed, a 2017 literature review of studies published in the journal Sports Medicine found “no direct or consistent research” of trans people having an athletic advantage over their cisgender peers.

“In relation to sport-related physical activity, this review found the lack of inclusive and comfortable environments to be the primary barrier to participation for transgender people,” the authors wrote.

For over a decade, the NCAA has required transgender women to be on testosterone suppression treatment for a year before they are allowed to compete on the women’s team.

Yet in January, a month after Thomas’ record-setting pace at the Invitational, the NCAA said it would take a sport-by-sport approach to its rules on transgender athletes’ participation and defer to each sport’s national governing body.

USA Swimming then released a set of stricter guidelines that require elite trans woman athletes to have three years of hormone replacement therapy and to prove to a panel of medical experts that they do not have a competitive advantage over cisgender women.

The new rule threatened to make Thomas ineligible to compete at NCAA championships in March. However, the NCAA said those rules will be instituted in a phased approach over the coming seasons rather than in the middle of this season.

Despite the out of pool controversy, Thomas showed no outward signs of stress or frustration at the Ivy League’s women’s swimming championships this week. With a calm and cool demeanor, she did precisely what was expected of her. She cheered on and high-fived teammates, chatted with coaches and fellow swimmers and sped past the competition on her way to three individual titles.

She is not even the lone trans athlete to win a race in the same pool at Harvard. Yale’s Iszac Henig, a transgender man, won the 50-yard freestyle in a pool-record 21.93 seconds on Thursday and came in a close second to Thomas in the 100-yard freestyle. The NCAA allows trans men to compete on the women’s team so long as they have not had hormone therapy.

On the far side of the pool, Thomas closely watched the end of the 50-yard freestyle race and clapped in excitement upon Henig’s win, a rare display of enthusiasm from Thomas at the meet. A day later, Henig and Thomas struck up a conversation at the far end of the pool, chatting and laughing as they leaned against the pool ropes.

They spoke for a few minutes until Thomas took off to get back to her work. She had more laps to swim.

CNN’s Elizabeth Wolfe contributed to this report.