Editor’s Note: Timothy Naftali is an associate clinical professor of public service at New York University and a CNN presidential historian. As the former director of the Presidential Recordings Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, he worked with the Lyndon B. Johnson tapes. Read more opinion on CNN. To learn more about LBJ’s career, tune into “LBJ: Triumph & Tragedy” premiering Sunday, February 20 and Monday, February 21 at 9 and 10 p.m. ET on CNN.

Although Americans can and do disagree about the individual achievements of our presidents, we still share a habit of comparing and contrasting them, of seeking for every new chief executive a twin or parallel among past occupants of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. President Joe Biden is most often compared to and judged against President Lyndon Baines Johnson, the architect nearly two generations ago of the modern American social safety net and a powerful warrior against poverty and racial injustice.

Although flawed, this comparison tells us as much about ourselves as these two presidents.

On the eve of the 1964 election, sensing the massive political victory to come, President Lyndon Johnson told his supporters in Austin, Texas, “I have spent my whole life getting ready for this moment.” Still grieving the shocking murder of John F. Kennedy, LBJ’s America yearned for national leadership in an era defined by a powerful and growing nonviolent civil rights revolution at home and fears of a Cold War becoming a hot war abroad. And LBJ was eager to provide that leadership.

Although never as certain of victory, Joe Biden could be forgiven for believing by January 2021 that his long public service was reaching a similar crescendo of immense promise and opportunity. He took the Oath of Office amid a pandemic that had already killed 400,000 Americans, after months of huge peaceful demonstrations across the country bespeaking the urgency of finally eliminating racial injustice, and only days after a violent right-wing insurrection in Washington DC, inspired by an outgoing President who refused to accept his electoral defeat.

Besides this shared sense that they were qualified for the immense challenges of their time, Biden and LBJ also both believed that the country craved more than the competent pragmatism that had defined their long tenures as US Senators. Both men thought the national traumas that gave birth to their presidencies would create a magnetic pull to the left.

They both ran on platforms that were more progressive than the legislation they had championed in their years in Congress and more ambitious than the agendas put forward by the younger, more charismatic (yet more cautious) men to whom they had been loyal vice presidents. LBJ embraced civil rights reform specifically designed to destroy the Jim Crow South whose voters he had represented all of his adult life. And he tirelessly fought to achieve the Great Society, an expansion of the New Deal social safety net that contrasted sharply with his bipartisan cooperation in the 1950s with the cost-cutting Eisenhower administration.

For his part, once he secured the Democratic nomination, Joe Biden became the cheerleader for policies introduced to mainstream US politics by his more progressive former rivals Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren – student debt forgiveness, managed trade, free Pre-K and federal paid family leave.

But, so far, the legislative comparison stops there: with ambition, not achievement. The similarities and the differences between these two Presidents tell the story of our own political moment and should be a cautionary tale about the conditions that usually produce transformational change in this country.

The next LBJ?

In a burst of legislative activity rivaled only by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first term, LBJ converted his potential into a new relationship between the American people and their national government. By the time LBJ hit his first major post-election roadblock (Congress’ refusal to endorse home rule for the District of Columbia in the fall of 1965), Johnson had signed into law a new Social Security Act that introduced guaranteed health care for the elderly (Medicare) and the poor (Medicaid), the Voting Rights Act, the Immigration and Nationality Act, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Housing and Urban Development Act, the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act, the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act and the text of what would become the 25th Amendment of the Constitution (on presidential succession and disability).

At the beginning of his term, Biden sounded unmistakably Johnson-esque: “The biggest risk is not going too big… It’s if we go too small.” Influential progressive Democrats echoed his ambition and its implied optimism – leaving behind, at least publicly, their earlier skepticism of Biden’s commitment to their agenda. The leader of the powerful Congressional Progressive Caucus, Rep. Pramila Jayapal, told The New Yorker, “It’s a progressive moment. It’s a populist moment. It’s an urgent moment.”

After a year’s worth of effort – despite some smaller victories in fighting poverty and inequality with the Covid-19 relief bill and the infrastructure bill – the President seems no closer to fulfilling the achievements that he touted as signatures of progressive success. Initially presented with a $3.5 trillion dollar price tag, his Build Back Better initiative shrank with each successive effort to negotiate a version that could pass in the Senate. Last month the President effectively declared the latest version, weighing in at about $1.75 trillion, dead on arrival due to persistent opposition from Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. Whereas there remains some hope that pieces of the initiative, perhaps designed to harness federal resources to fight climate change, may be achieved as stand-alone bills, there appears to be no hope of passing a 21st century voting rights bill in honor of the civil rights hero John Lewis to undo the erosion of the rights guaranteed in the LBJ moment.

What went wrong? Some observers, such as Robert Reich, labor secretary in the Clinton administration, have focused on Biden himself as the problem. “It’s time for (Biden) to assert the kind of leadership LBJ asserted more than a half-century ago on civil and voting rights,” he wrote last spring.

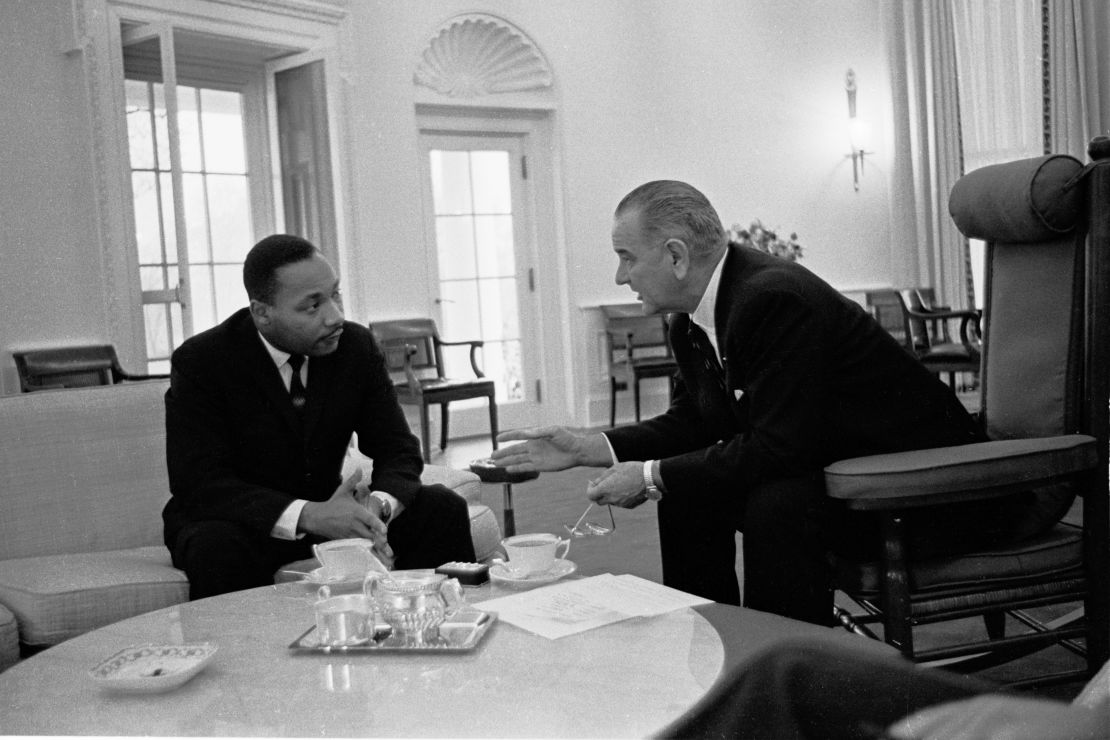

Johnson used every tool at his disposal, described by journalist Mary McGrory as “an incredible, potent mixture of persuasion, badgering, flattery, threats, reminders of past favors and future advantages.”

Yet it is safe to say that Reich’s recipe would not have produced the required results this time around. To understand why Biden has fallen short of expectations and rhetoric, we need to know what made LBJ and the liberal legislative achievements of 1965-67 possible. They came in the wake of LBJ’s landslide victory. LBJ pummeled the Republican Barry Goldwater, winning 61% of the popular vote and 486 electoral votes. Outside the South, where Goldwater was admired for his opposition to federal civil rights legislation, the GOP nominee carried almost no congressional districts. This was the most definitive endorsement of a Democratic candidate since the height of FDR’s power in 1936.

Even more importantly as an explanation of the legislative achievements to follow, LBJ had coattails. By expanding their control of the Senate by two, 68-32, and gaining 37 seats in the House to command a 295-140 majority, LBJ’s Democrats were in their best position in a generation to break the stranglehold of the bipartisan Conservative coalition in Congress, which in the House controlled at least 100 Southern Democratic votes and over 100 Midwestern and Western GOP votes. The newly elected LBJ Democrats came from outside the South and supported liberal legislation.

How the Master of the Senate took control

Johnson had longed to have this opportunity. In 1959 and again in 1960, as Senate Majority Leader and then vice presidential candidate, LBJ had deployed “The Johnson Treatment” – a tactic of knowing each legislative leader’s pressure point and driving home the need for a vote – in support of liberal legislation and failed epically so long as southern Conservatives could use the filibuster in the Senate and had a stranglehold on the Rules Committee in the House and Eisenhower had the veto pen. As president, and with a larger liberal caucus within the Democratic caucus, Johnson would try again.

“Now, the sky’s the limit for you,” Johnson told his younger vice president, Hubert Humphrey, in a conversation he recorded in March 1965, as their administration began its push for the Great Society: “There are 104 bills, and they’re all yours and mine on the ticket, because that’s what we ran on; that’s our platform; that’s our program. You’re half of it, and you’re there every day. And you just help us if you can. And when you get it passed … you can say, ‘We passed education. We passed Appalachia. We passed medical care.’ And if you give me those, I’ll get – I’ll have a majority two years from now.”

And for a time, magic happened. The 89th Congress went on to approve 68.4% of Johnson’s proposals in 1965, according to Rowland Evans’ and Robert Novak’s book about LBJ. In 1963, just two years earlier with Kennedy in the White House, the number had been an anemic 27.2%.

As my CNN colleague Julian Zelizer makes crystal clear in his insightful “The Fierce Urgency of Now,” this achievement came less from the force of his character or personality and more from the power he suddenly wielded. In arguing for a less “Johnson-centric view,” Zelizer underscored the importance of the mandate that LBJ and Democrats, in general, received both in the streets and at the polls in 1964.

In 2020, Joe Biden won a solid victory over Donald Trump, but nothing about it was massive; he gained 51.3% and not 61% of the popular vote. His was not the kind of landslide that puts the fear of God – or of the president – in legislators. And his coattails were slender. Democrats did not win in a similar fashion in Congress. Nancy Pelosi’s caucus shrank by 13 to 222. Chuck Schumer became Majority Leader but with an evenly divided Senate, 50-50. Unlike Barry Goldwater in 1964, Donald Trump was not repudiated. He beat Biden in 210 congressional districts, which meant representatives from those areas had little reason to be concerned about bucking the new sheriff in town.

That wasn’t Biden’s only political handicap. Although Johnson’s Democratic Party, which included White supremacists as well as liberals, was more deeply divided than today’s Democratic Party, LBJ had a governing majority in Congress for his agenda. He could rely on enough crossover voting from liberal Republicans in the House and Republican allies of civil rights in the Senate. Thirty GOP senators and 112 members of the House supported the Voting Rights Act. Seventy Republicans joined 189 Northern and Western Democrats to pass Medicare in the House and 13 Republicans voted “aye” in the Senate.

When the Congressional Progressive Caucus, comprising 95 of Pelosi’s 222 votes in the House, held up the Senate’s bipartisan infrastructure bill until there were promises from every Democrat in the Senate to pass the $2 trillion version of the Build Back Better Bill, the Speaker could not fill the gap with Republican votes.

The puzzle of Biden’s missed moment

The puzzle is why this President and his most activist allies so misjudged 2021. Part of the answer can be found in the difficulties of differentiating between social and political power. The vote totals after the 2020 election and the razor-thin nature of the Democrats’ Congressional majority made clear that it wasn’t 1964, when social change and activism and political action went hand in hand.

But nonetheless, many held a belief that – especially in this social media age – Congress could be moved by the powerful mobilization of the base of the majority party after the murder of George Floyd and the disgust among many following the January 6 insurrection. Both suggested a possibility for a new kind of grassroots-led governing coalition in Congress, that perhaps the TikTok Nation could overwhelm the Trump Nation despite lacking a sweeping mandate at the polls.

In this analysis, though it wouldn’t have been an LBJ moment, it could have been a Biden-and-Democratic-progressives moment, something new in US political history. In its first weeks, the 117th Congress passed a huge pandemic relief bill, with elements that temporarily addressed some social inequities, and though the ultimate bipartisan infrastructure bill was slimmed down, it still represented the largest capital investment in the nation’s transportation and communications networks in 60 years. Like LBJ, Biden sought more.

But Biden couldn’t get more. Here the comparison with LBJ is instructive. Six decades ago, the Texan had an advantage in dealing with his divided party that Biden lacks: LBJ was trusted by those from whom he needed compromise for Congress to pass his reforms. Although he angered fellow Southerners, he was one of them. And if he couldn’t get their support for civil rights, he might have it for anti-poverty programs that would help their constituents.

Biden, whose career in the Senate was marked by pragmatic compromise, is not trusted by progressives. Although we need to learn more to be sure, Biden’s strategy of going for broke may have been his way of building that trust, even though the strategy itself held out little hope of legislative success.

It’s not 1965 anymore

Indeed, that strategy weakened Biden’s ability to seek GOP votes and delayed getting any piece of social legislation while Biden was still enjoying his modest honeymoon period. Republican support was key to LBJ’s landmark successes in the Great Society. But Biden is governing in a much more partisan time than 1965. With a few exceptions, his bills have to pass with Democratic votes or not at all, meaning that the party’s intramural struggle ultimately defines success.

Congressional politics alone doesn’t explain the inability to turn popular dissatisfaction with the status quo into legislative achievement. For presidents to overcome the procedural conservatism (traditional stand-pat-ism) of congressional leaders, those leaders need to fear the wrath of their supporters for inaction. Biden hasn’t been able to generate that fear on Capitol Hill because he has never been as popular a president as LBJ was when he started out.

Biden’s opposition is also much more robust, unified and effective than Johnson’s. Although disgraced, the losing candidate in 2020 and his would-be successor clones retain a huge influence on Capitol Hill. As the 89th Congress began passing the Great Society programs, Barry Goldwater wasn’t a factor. LBJ’s approval rating hovered in the mid to high 60s. By comparison, Biden didn’t even start his presidency with 60% approval and once the Delta variant upended optimistic predictions of a vaccine-induced end of the pandemic and the administration suffered a self-inflicted humiliation in Afghanistan, support for Biden dipped below 50%, and now resides in the low 40s.

So, to no one’s surprise, Biden’s first year wasn’t 1965. The surprise for some may be that our times also didn’t reflect the end of all of the rules of political gravity that traditionally affect presidential performance in Congress. This isn’t like the moment that LBJ mastered so brilliantly. It is much, much harder, politically, and Joe Biden is not LBJ.

Instead, Biden should be assessed on his own terms and in the context of his own time. With almost no margin for error in either House of Congress, an ideologically diverse (let alone iconoclastic) caucus, a partisan Republican bloc, and amid a politically divisive pandemic, it is remarkable Biden got much of anything passed. It turned out he had and may still have a pragmatic governing majority. The President and his congressional allies might keep that in mind as they consider how to make effective use of the power they do have before the midterms this November, when they will face the voters again and ask for more.