A child’s tooth unearthed from a French cave has revealed the earliest evidence of humans – Homo sapiens – living in western Europe.

The discovery of the molar from Grotte Mandrin, near Malataverne in the Rhône Valley in southern France, along with hundreds of stone tools dating back about 54,000years ago, suggests that early humans lived in Europe about 10,000 years earlier than archaeologists had previously thought.

What’s more, the Homo sapiens tooth was sandwiched between layers of Neanderthal remains, showing that the two groups of humans coexisted in the region. These findings challenge the narrative that the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe triggered the extinction of Neanderthals, who lived in Europe and parts of Asia for about 300,000 years before disappearing.

“We’ve often thought that the arrival of modern humans in Europe led to the pretty rapid demise of Neanderthals, but this new evidence suggests that both the appearance of modern humans in Europe and disappearance of Neanderthals is much more complex than that,” said study coauthor Chris Stringer, a professor and research leader in human evolution at the Natural History Museum in London.

It’s the first time archaeologists have found evidence of alternating groups of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals living in the same place, and they rotated rapidly, even abruptly, at least twice, according to the study that published in the journal Science Advances on Wednesday.

Previously, the arrival of early humans in Europe was dated to between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago, according to remains found in Italy and Bulgaria – not long before the last surviving Neanderthal remains dating back 40,000 to 42,000 years ago were found. This time frame had led many to think the arrival of Homo sapiens and the disappearance of Neanderthals were inexorably linked.

Humans and Neanderthals, who we know from genetic analysis encountered one another and had babies, resulting in Neanderthal traces in our DNA, overlapped for a much longer period in Europe, this study suggests.

Clues from ancient stone tools

Did humans and Neanderthals hang out together in this French cave overlooking the Rhône valley? The researchers don’t have any hard evidence of interaction between the two groups.

The tools found in the layers representing the Homo sapiens and Neanderthal occupations are distinct in style and don’t show any sign that they taught one another knapping or flaking stoneworktechniques. The stone tools associated with humans, known as Neronian tools, are smaller than those used by Neanderthals, known as Mousterian tools.

But the authors feel that it’s likely that the two groups must have bumped into one another in the neighborhood – even if direct contact didn’t take place in this particular cave.

The hundreds of stone tools found at the site suggest that the rock shelter was occupied intensively by both groups of humans – and was not just a place for an occasional stopover.

Astonishingly, the team was able to determine that the period between the Neanderthals relocating and the first modern humans moving into the cave 56,000 years ago was just one year. The researchers did this by mapping and analyzing soot deposits from fires made by humans in the cave.

“The soot is deposited to the roof of the rock shelter, and when there was a period of no one living there, there’s no soot deposition,” explained Stringer.

Lead author Ludovic Slimak, a researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and the University of Toulouse who has been working on the site for 30 years, said he believed the two groups must have exchanged knowledge in some way.

Right from the beginning of their occupation, Slimak said, the modern humans were using flint sourced from hundreds of kilometers away, the stone tools found in the cave show. That knowledge likely came from the indigenous Neanderthals, Slimak explained.

“The territory appears to be immediately well known by Homo sapiens, and they immediately know flint sources that are very localized,” he said.

“What precisely was the interaction? We just don’t know. We have no idea whether it was good relationship or a bad relationship. Was it a group exchange or did they have (Neanderthal) scouts to show and guide them?”

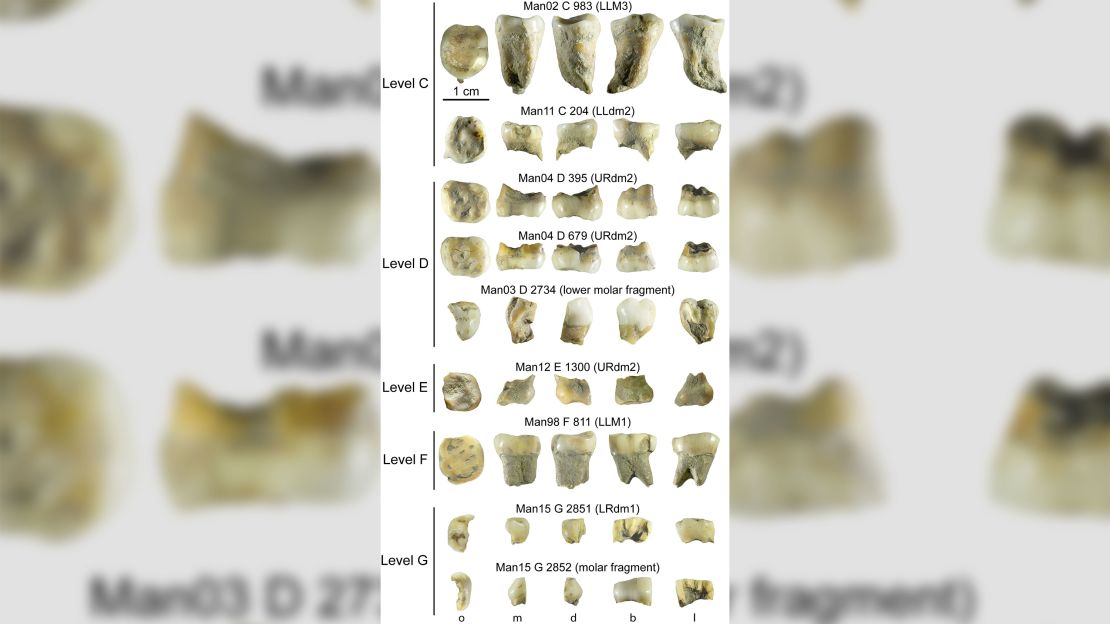

The researchers dated the site’s layers using radiocarbon and luminescence techniques, which measure the last time grains of mineral in rock were exposed to sunlight. The layer containing the Homo sapiens child’s tooth spans 56,800 to 51,700 years ago. In different layers, the scientists discovered eight other teeth that belonged to Neanderthals.

Untangling the human story is a complicated endeavor, but it’s largely accepted that modern humans originated in Africa and made their first successful migration to the rest of the world in a single wave between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago.

Different ancient hominins existed and coexisted before Homo sapiens emerged as the lone survivor, and there was interbreeding between different groups of early humans. Some of these groups – like Neanderthals – are easily identified through the fossil record and archaeological remains, but others – like the Denisovans – have been largely identified by their genetic legacy.

DNA could flesh out the story

Marie-Hélène Moncel, a research director at the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris, said that the discovery of just one modern human tooth wasn’t enough to definitively push back the dates of the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe. She said other fossilized human remains were needed to be sure of this paper’s findings.

“Teeth are not enough, we must find post-cranial or cranial remains to be sure,” said Moncel, who wasn’t involved in the research.

It’s possible that DNA – either directly from the teeth or through groundbreaking new techniques that allow DNA found in sediment to be sequenced – could flesh out the story and tell us how the pioneering group of early modern humans were related to the ones that arrived later and whether the Neanderthals who lived in the cave had the same origins.

The DNA might show evidence of interbreeding between the two groups. In Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria, where the previously oldest evidence of Homo sapiens in Europe was found, the DNA of those early modern humans was about 3% Neanderthal.

Teeth preserve well in the fossil record, and their bumps and groves are a bit like fingerprints for archaeologists, giving clues to ancestry and behavior. The shape of the tooth and its internal structure strongly suggested it belong to a modern human child even though the tooth was damaged, the researchers said.