Students in Flint Community Schools have only been in the classroom about six months over the past two years due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and after the district’s announcement last week that distance learning would continue until further notice, some families – including some still dealing with the city’s water crisis – aren’t sure how much longer they can keep it up.

“I have to be able to make a living so that I can pay for a roof over our heads, so I can pay for food. And if I can’t have someone who can sit with the kids during their school hours then I have to, so I am not going to work,” Lakia Cannon told CNN after helping her children, Khaterius, 9, and Kalia, 8, with their homework.

Citing a recent surge in Covid-19 cases, Flint Community Schools announced Wednesday it’s unknown when students will return to the classroom. They were originally slated to return to in-person learning Monday.

The decision is a contrast to school districts in cities including Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York, where officials have pushed to keep schools open amid rising case numbers.

Cannon said she appreciates the district is trying to keep students safe, but she struggles with the indefinite extension of remote learning. “I am conflicted. We need more options. We need more flexibility. We need something to help us out in this,” she said.

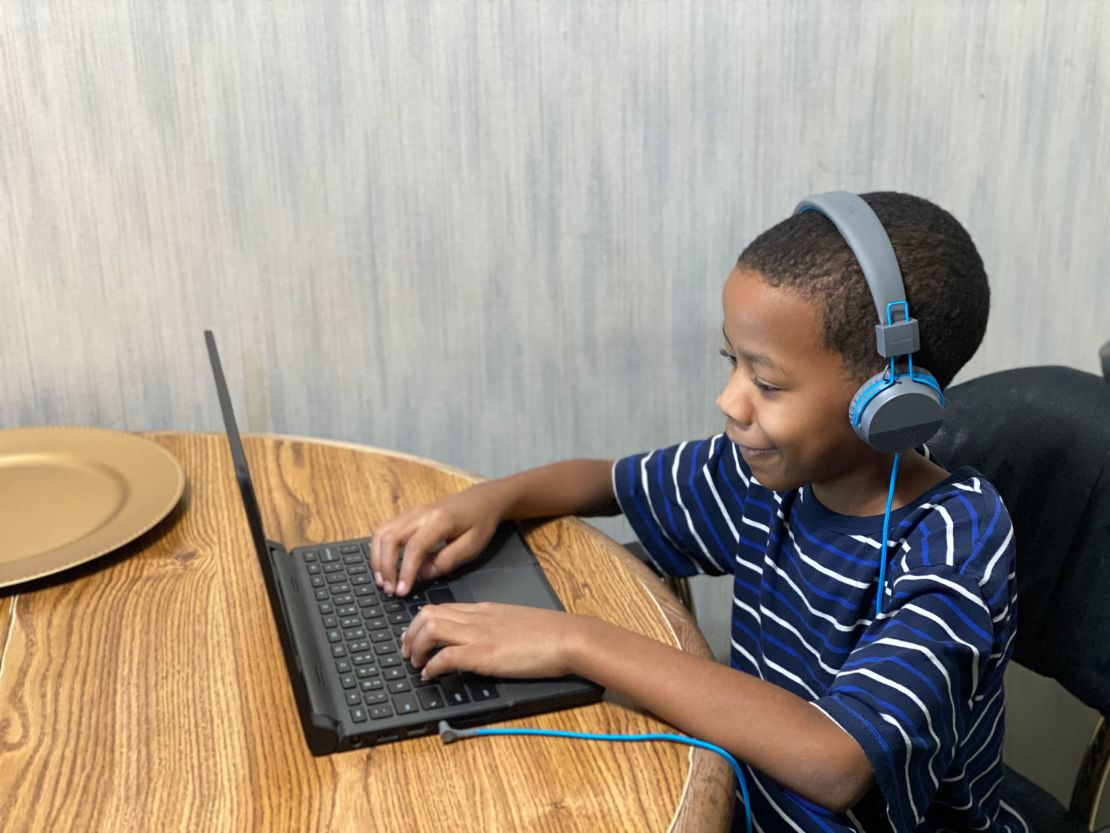

Cannon’s mother, Beverly Lewis, helps out by bringing the children to a local senior community center where she is the director. They study in a conference room across the hall from Lewis’ office. It’s an option many families don’t have.

“It really creates issues for us at home … We are very limited on who we can have be home with them to make sure that they are doing their school the way that they need to or to give them a little push if they need some pushing or assistance,” Lewis said. “It has been very difficult.”

“I want to go back to regular school,” Khaterius said while working on a science presentation for this fourth grade class. He said he misses his teacher and extracurricular activities like breakfast club, the most. His sister, Kalia, said she misses talking to and eating with her friends.

Superintendent says safety comes first

The week the school district decided to continue remote learning, January 12-18, Michigan’s statewide seven-day average test positivity rate hovered just above 33%, according to the University of Michigan’s MI Safe Start dashboard. Genesee County, where Flint is located, reported an average positivity rate of 38.9%, the data showed. The county is currently classified as having a high rate of transmission, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC has said multiple studies show transmission of Covid-19 in school settings is usually lower than or similar to community transmission when districts put the right prevention strategies in place.

But the superintendent of Flint Community Schools, Kevelin Jones, stands by his decision to continue remote learning indefinitely.

“We didn’t want to have our scholars out for two weeks and then, all of a sudden in the middle of a surge, we send them back to school,” Jones said. “And so we made the decision to have them out until this surge begins to decline.”

The hope is that students will not be out for the remainder of the school year, he said. “Absolutely not. It is our goal to have our scholars in school, however, safety is first for Flint Community Schools.”

The decision to continue remote learning comes with guidance from city health officials and support from the school board, he added.

The district was allocated nearly $150 million in federal funds to make improvements to slow the spread of the virus, Jones said. There are air purifiers in each classroom, but the HVAC systems are currently being upgraded.

“Our ventilation is not where it needs to be to ensure total safety, and so we are working at that and we’ve been working at that for the last year or so,” Jones said. “We are doing renovations, purchasing PPE supplies, technology for scholars and medical assistants, etc. It’s not just for air quality.”

“You can have all the money in the world. But if you don’t have the people there to enforce the distancing rules, if you don’t have teachers …. because they’re at home sick, then what good is money?” Carol McIntosh, a Flint Board of Education member and trustee, said.

“At the end of the day, we need educators available and our teachers are paying the price … Some of our teachers might not be able to make it back from Covid and we already have a teacher shortage in the country,” she said.

McIntosh also said she understands the concern among parents, adding she has received criticism from people outside of the district about the decision.

“We believe that the best form of teaching our scholars is having them face-to-face,” she said. “But we also understand that if we send sick kids home, it is a chance that those kids could become orphans. And I think that is just too high of a price to pay at this time.”

Jones, whose own children are among the district’s 3,000 students, said he isn’t willing to risk losing anyone again.

“I lost my father. I lost my hero. I hear him in the back of my head saying ‘Make sure you’re doing what’s best for children,’” he said, adding that Covid-19 also killed his uncle and nephew a week after his father died.

A Covid survivor himself, Jones said distance is the best option right now.

“To our scholars, you’re going to be able to see your friends, you’re going to be able to mingle, but right now, let’s just stay safe. Hang in there,” he said.