Carjackings have risen dramatically over the past two years in some of America’s biggest cities.

Just outside Chicago, a state senator’s car and other valuables were taken at gunpoint in December, and a group of children, one just 10 years old, carjacked more than a dozen people. A rideshare driver being carjacked shot his attackers earlier this month in Philadelphia. Last March, a 12-year-old in Washington, DC was arrested and charged with four counts of armed carjacking.

“The majority of it is young joyriders. They’re not keeping the cars. They’re jacking cars to commit another crime, typically more serious robberies or shootings, or joyriding around for the sake of social media purpose and street cred,” said Christopher Herrmann, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “It’s a disturbing trend.”

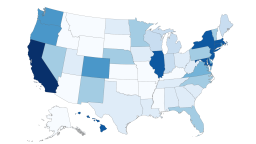

Comprehensive national data isn’t available because the FBI’s crime reporting system doesn’t track carjackings. But large cities that track the crime reported increases in 2020 and 2021, especially as the pandemic took hold of the country.

- The number of carjackings quadrupled in New York City over the last four years, according to data released by the NYPD. The city recorded more than 500 carjackings in 2021, up from 328 in 2020, 132 in 2019, and 112 in 2018.

- Carjackings in Philadelphia nearly quadrupled between 2015 and 2021, according to figures released by the city’s police department. They recorded more than 800 last year, up from about 170 in 2015.

- In New Orleans, there were 281 carjackings last year, up from 105 in 2018, the earliest year of available data. The city has also seen a string of carjackings this year, with NOPD reporting 39 as of January 21.

- More than 1,800 carjackings were reported in Chicago last year, the most of any large city, according to data released by police departments to CNN. Chicago’s 2021 tally was the most on record over the last 20 years. Carjackings had been steadily declining in the city after 2001, hitting a low of 303 in 2014, but began to tick upward before skyrocketing to 1,400 in 2020 following the onset of the pandemic. Last year saw more than five times as many carjackings as in 2014.

‘We recognize the fear and uncertainty’

“It is lawless,” said Raymond Lopez, an alderman for Chicago’s 15th Ward. “It doesn’t feel lawless. It is.”

Chicago’s clearance rate for carjackings is low, and has further declined during the pandemic. According to the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab, only 11% of carjacking offenses resulted in an arrest in 2020, down from 20% in 2019. Just 4.5% of offenses resulted in charges approved by the State Attorney’s Office.

Chicago, a city of 2.7 million people, recorded more than three times as many carjackings as New York, where the population is almost three times higher. Chicago police officials declined to comment.

Philadelphia police posted a message on Facebook telling residents they were prioritizing the solving of carjacking cases and that more officers had been dedicated to that task.

“We recognize the fear and uncertainty these incidents bring, as the victims in these cases have touched nearly every demographic,” the statement read. “The PPD has deployed additional resources to investigate these incidents and apprehend offenders.”

In December, Pennsylvania Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (D) was carjacked at gunpoint in Philadelphia – a 19-year-old from Delaware was later arrested for the crime. News outlets in Philadelphia have reported more than 100 carjackings have already taken place so far this year.

There are problems tracking data

Many cities do not have data on carjackings readily available, as police departments will often categorize these crimes as robberies or assaults. It’s difficult to understand the scope of the problem at a national level because the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program, which law enforcement agencies voluntarily submit their crime data to, does not track carjackings.

However, more agencies are beginning to track carjackings separately. Dallas began classifying these crimes separately from robberies in their data last year and reported 453 carjackings in 2021. The Metropolitan Police Department in DC last year created a task force dedicated to addressing carjacking and auto thefts. Reports of auto thefts are also up across the country and are more reliably tracked than carjackings.

Kim Smith, director of programs at University of Chicago’s Crime Lab, says that tracking crimes in greater detail is a key part of finding solutions.

“I do think it’s important to be as granular as possible when you’re collecting data on crime,” she told CNN. “Who are the victims? Where do things take place? A lot of carjackings are done with a gun. If we’re trying to address gun violence, then we need to be as granular as possible.”

More detailed reporting also makes it easier to spot trends and patterns – in its 2021 report, “How the pandemic is accelerating carjackings in Chicago,” the Crime Lab found that the majority of carjackings were concentrated in the south and west sides of the city, where gun violence is disproportionately high. The majority of the victims of carjackings were Black or Hispanic.

Smith says she hopes the detail provided in the Crime Lab report can encourage officials in other cities to take a closer look at the circumstances under which these crimes occur. “There’s a lot that surprised us in the analysis, and I do think some of this is a call to action,” she said.

Some ‘emboldened to be repeat offenders’

Shifting attitudes toward the juvenile justice system, and Covid-related restrictions aimed at reducing the number of people in county jails or juvenile facilities, has created a situation where accused criminals who’d normally be held in custody are free while awaiting trial, experts told CNN.

That’s created a “revolving door” situation where “some were emboldened to be repeat offenders,” said Jeffrey Norman, chief of the Milwaukee Police Department. “We saw this on a higher level in 2020 and 2021.”

In Chicago, Lopez said people arrested and sent home with electronic monitoring sometimes reoffend while awaiting trial for something they’ve been arrested for.

“It’s like the perfect storm, where all these soft on crime policies have come to a head during this pandemic,” he told CNN.

The Crime Lab’s study of Chicago’s carjackings found that almost half of all carjacking arrestees in Chicago in 2020 were under 18. Between 2019 and 2020, there was a 104% increase in the number of arrestees who were minors. For many of them, it was their first contact with the criminal justice system, according to Smith.

The increase in carjackings committed by minors underscores the extent to which the pandemic has impacted young people in America – especially in areas that were already struggling. The report states that carjackings occurred with more frequency in areas with poorer internet access and lower school attendance.

Smith noted that kids living in areas with lower internet access had fewer opportunities to engage in school, remote learning and program providers over the past two years. “The impact of the pandemic, I think, can’t be overstated,” she said.

Lopez said the choice to not take crime seriously among young teens will have consequences years later when they age out of the juvenile justice system.

“When you have carjackers who are 15 on their third car, that’s a problem,” he said.

Norman, the Milwaukee chief, said it would take a multi-faceted approach to begin addressing the rise in carjackings.

“You’re not going to police your way out of this,” Norman said. “Everyone has to share responsibility when it comes to kids.”

Norman said that the behavior of children in a community were like “canaries in a mine. When a community has issues, kids are falling to particular types of behaviors.

“This is my thing. When a child doesn’t love himself or herself, I worry about the community that has that child. That’s no holds barred behavior that child will be engaged in,” Norman said. “A hungry kid will do whatever it takes to put food in his stomach.”

The closure of schools and advent of remote learning, the stress within households related to that and economic insecurity, and the pandemic stress on other institutions have all contributed to teens having more free time and less stability in their lives.

“You don’t take care of basic things, you can’t get to self-realization,” Norman said. “Not every kid is out doing things to put food in their stomach. But there are things not being take care of – whether it’s having positive mentorship, or areas of socialization not (being) available.

“It’s sad seeing despair and the lack of resources any normal kid should have,” Norman said. “As the old saying goes, ‘Idle hands are the devil’s work.’”

CNN’s Christina Carrega and Pervaiz Shallwani contributed to this report.