The last four times a president went into midterm elections holding unified control of the White House, Senate and House of Representatives, as Joe Biden and Democrats do now, voters have revoked it.

It happened to Donald Trump in 2018, Barack Obama in 2010, George W. Bush in 2006 and Bill Clinton in 1994: All lost control of at least one congressional chamber, crippling their ability to advance their legislative agendas. In fact, no president who went into midterms with unified control of government has successfully defended it since Jimmy Carter in 1978, when Democrats were still cushioned by the enormous margins they amassed in the backlash against Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal.

That’s the foreboding history heightening Democratic anxiety about their struggle to move the key pillars of their economic and voting rights agenda past the resistance of Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona.

Over the past roughly 50 years it has grown much more difficult that it was earlier in the 20th century for either party to achieve, and especially to sustain, simultaneous control of the White House and both congressional chambers. Moreover, since the 1970s, neither party has regained unified control of government faster than 10 years after losing it.

With unified control now typically expiring quickly and returning only slowly, both parties have felt enormous pressure to squeeze as much of their legislative agendas as possible into the brief, and widely separated, windows when they hold all the levers of government.

That instinct has fueled the Democratic urgency about passing Biden’s sweeping Build Back Better bill – which represents a compendium of party priorities that have accumulated since Democrats last held unified control of government, in Obama’s first two years – as well as the twin voting rights bills nearing make-or-break Senate votes later this month. It also explains why Democrats are so nervous about the possibility that resistance, in various forms, by Manchin and Sinema could block either or both of those huge party priorities.

Among Democrats, there’s a widespread fear that if Manchin and Sinema prevent them from moving these bills into law in the current legislative session, it may be years before they get another chance. The difficulty both parties have faced holding unified control for any sustained period over the past half century suggests that anxiety is entirely justified.

Unified government was more the norm

Divided government – in which one party holds the White House and the other holds one or both chambers of Congress – has become so routine in modern politics that it’s easy to forget what a departure it represents from the dynamics through the heart of the 20th century. For most of those decades, the country’s default instinct was to give one party the keys to government and say, in effect, you drive for a while.

From 1896 to 1968, one party or the other simultaneously controlled the White House and both congressional chambers for 58 of those 72 years. Unified control was not only common, but it also was often extended. Early in that period, Republicans held a governing trifecta for 14 consecutive years (1896 to 1910) under Presidents William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft; later Democrats matched that achievement under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman from 1932 to 1946. Republicans controlled all three branches for the entire decade of the 1920s; Democrats controlled all three branches from 1961 through 1968.

Since 1968, the story has been very different. One party or the other has held unified control of government for just 16 of these past 54 years. Neither side has maintained unified control since 1968 for more than four consecutive years. Carter did that throughout his only term (though his congressional majorities depended on very conservative Democrats from what was then still the one-party South who often voted against him.) Bush also had a four-year span of control.

(Bush’s story is complicated: After the razor-thin 2000 election, he came into office with unified control but lost it within months when disaffected GOP Sen. Jim Jeffords of Vermont quit the Republican caucus and shifted the majority in the previously 50-50 Senate to the Democrats. In the post-9/11 election of 2002, Republicans maintained control of the House and regained the majority in the Senate. Bush defended those majorities in his 2004 reelection, but in 2006, the first time he went into a midterm with unified control, Republicans lost both chambers.)

Bush’s loss of his congressional majorities in the 2006 midterms was typical of the modern experience. Clinton, Obama and Trump all came into office with unified control of government and then lost it in their first midterms, with Obama and Trump surrendering the House and Clinton losing both chambers, to the other party.

Veterans of both the White House and congressional leadership agree that growing awareness of these trends has encouraged each side to front-load as much of its legislative agenda as possible into its first two years. David Axelrod, the top political strategist for Obama, who’s now a CNN senior political commentator, says that administration was “unequivocally” aware of the likelihood it would not preserve unified control past its first midterms.

“Even before we took office, we knew the economic catastrophe we were inheriting, which promised to be long and deep, meant we faced a calamitous midterm,” Axelrod told me in an email. “That meant if we wanted to accomplish anything meaningful, it would have to come in the first two years, when we had large majorities in both chambers. It’s why President Obama moved the Affordable Care Act when he did.”

Brendan Buck, the counselor to House Speaker Paul Ryan when Republicans held unified control under Trump in 2017, likewise says that “we were well aware … that our time was fleeting and the window was closing just as soon as we took over. That shadow of history was hanging over us the entire time. … It made us aware that this was the window we have and we are going to throw everything we have on it.”

Biden has clearly followed these tracks, reaching a bipartisan agreement to increase infrastructure spending, consolidating a wide range of Democratic domestic priorities into his sweeping Build Back Better bill and now pushing hard to pass new federal voting rights legislation, even if that requires changing the Senate filibuster rule.

“Today, the White House and Democrats rightfully suspect that at least the House will turn in ’22, so this brief moment of one-party control, albeit narrow, offers the last, best hope for the president and members to get big priorities done,” Axelrod says. “That’s why there is such urgent anxiety about loading up the Build Back Better Act with so many planks.”

Does chasing big legislative wins help or hurt?

While the shift in strategy is visible, less clear is its effect. Political practitioners and political scientists alike divide over whether passing a big agenda will improve Biden’s odds of defying these trends and maintaining unified control past 2022 – or compound the risk that he will surrender it in a bad midterm election, just like each of his four immediate predecessors.

One camp says that pursuing big legislative wins while holding unified control of government offers the best chance to avoid the usual midterm losses for the president’s party by encouraging its base voters to turn out in big numbers. Adam Green, co-founder of the liberal Progressive Change Campaign Committee, says that rank-and-file Democrats are especially eager for the party to deliver because the issues Congress is addressing carry such enormous consequences.

“I really do think that Democrats across the ideological spectrum feel a historic responsibility and urgency in this moment to protect our democracy and protect our climate,” Green says. “That’s different from maybe during the Clinton years, where it was ‘OK, an earned income tax credit would be nice.’ “

The other camp believes that the way the parties are reacting to the risk of rapid turnover –by squeezing so much of their agendas into early legislative blitzkriegs – paradoxically may be compounding the danger they’re meant to address. Buck, reflecting that view, argues that Biden is courting a big backlash by pursuing so many liberal legislative goals, just as Republicans did in 2017 by seeking to repeal the Affordable Care Act as their first major initiative.

“Typically when a new government comes in it is often a rejection of the previous regime and voters tending to vote for checks and balances,” he says. “But politicians tend to interpret that as an affirmation or endorsement of themselves and everything that they believe. … So you end up losing your majority because … you tend to overreach and people reject that.”

Compounding that risk is another dynamic. Since Democrats surrendered their governing trifecta with Jimmy Carter’s defeat in 1980, no party that’s lost unified control has regained it in less than 10 years. That means by the time each party has regained unified control, the wish list of policy demands and aspirations within its coalition has grown to intimidating length. Presidents have often devoted their brief windows of unified control to resuscitating those deferred dreams.

Obama, for instance, focused his two years with control of both congressional chambers primarily on passing a universal health care bill, the largest unmet Democratic priority from the Clinton presidency; Trump’s two years of unified control were consumed by the failed attempt to repeal that law, which Republicans had targeted since they had regained the House in 2011. Much of the Build Back Better agenda is centered on priorities that Democrats have pursued (such as universal pre-K) since Obama’s presidency. The problem, in each of these cases, is that much of the public has often seen these legacy agendas as not relevant to the immediate problems the country is facing.

“As often as not, it doesn’t really match what the demands of the time are,” says Daron Shaw, a University of Texas at Austin political scientist who advised Bush in his two presidential campaigns.

Why is divided government now more common?

Political practitioners and political scientists alike have struggled to explain why divided government has become so much more common in the past half century. Most of the academic explanations for the phenomenon centered on the period from 1968 through 1988, when Republicans dominated presidential elections but Democrats still controlled the House for all of those years and the Senate for most of them, notes Shaw. (Those explanations included the belief that the advantages of congressional incumbents made them too difficult to dislodge or the belief that voters inherently preferred Republicans exuding toughness for president and Democrats displaying empathy for Congress). But, Shaw says, “none of these [theories] do a particularly good job” of explaining the persistence of divided government since 1992, a period when Democrats have held the White House most years and Republicans have more often controlled the House and Senate.

The most persuasive explanation may be the most basic: Both parties are struggling to sustain unified control because the country is divided too closely and stably to allow it. There’s evidence the modern Democratic coalition is at least slightly bigger than the Republicans’: Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the eight presidential elections since 1992, an unprecedented streak since the formation of the modern party system in 1828. And if you assign half of each state’s population to each senator, Republicans have represented a majority of the US population in the chamber in only one session since 1980.

But Michigan State University political scientist Matt Grossmann notes the Democratic presidential popular-vote victories have usually been relatively narrow and that Republicans have more often won the national popular vote in House elections over that period. When you consider all those factors, he argues, “it’s really clear that it’s not a sizable majority for either political party.”

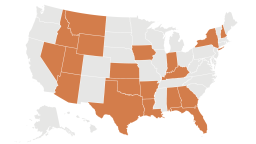

While the national balance between the parties may be precarious, it is also rigid. Especially in this century, the parties have solidified their control up and down the ballot in a large swath of states. Each party now holds fully 47 of the 50 Senate seats in the 25 states that voted for Biden or Trump in 2020. In a parallel development, the number of House members who win districts that vote for the other party’s presidential candidates has dwindled.

This growing alignment between the outcomes in presidential and congressional races has eliminated a key dynamic that helped parties maintain unified control for longer stretches during the earlier era. Through most of the 20th century, as Grossmann notes, each party could pad the size of its congressional majorities by electing senators or representatives who were ideologically out of touch with the national party but popular locally – the progressive Midwestern Republicans of the early 20th century, for instance, or the conservative Southern Democrats who persisted until the 1980s. Now that option has been virtually eliminated, as each party dominates the congressional elections in the states it also wins for president.

All of these factors combined have lowered the ceiling on the size of the House and Senate majorities that each side can amass in its best years. As I’ve written, since 2000 either party has reached 55 Senate seats just three times, far less than was common in the 20th century; likewise, since 1995, the majority party in the House has held at least 243 seats only two times – a level reached by the Democratic majority in every Congress from 1961 through 1994.

The effects of today’s polarization

Even when unified government control was more common in the 20th century, the governing party usually suffered significant losses in midterm elections. The difference then, as Grossmann points out, is that heading into the midterms their congressional “majorities were big enough to sustain the backlash.” With the parties now holding fewer seats even while in the majority, they have less cushion to maintain control when hit with the almost inevitable losses in the midterms. The risk of losing unified control in midterm elections has grown, Shaw says, because now the parties “are not insulated by these super majorities.”

Other factors have made it more difficult for the parties to sustain unified control. Many political professionals, such as GOP pollster Bill McInturff and Democratic data analyst David Shor, point to the erosion of the voter inclination to favor incumbents (the so-called “incumbency advantage”).

“Split ticket voters have largely disappeared,” McInturff told me in an email. “Voters are voting for party, which means lesser known challengers are getting a boost and upsets to even well-funded, relatively popular incumbent party Members of Congress are possible.” While challengers to entrenched incumbents often struggled before to raise money, McInturff adds, the nationalization of fundraising means “even modestly credible challenger campaigns are awash with outside money in ways that allow them to compete … and win campaigns they would have lost for lack of resources in earlier cycles.” The parties holding unified control also face the full glare of skeptical media attention without any cover from sharing authority with the other side.

Most analysts now agree Democrats face long odds of defying this history and holding both congressional chambers in 2022; that’s both because Biden’s approval rating is scuffling but also because the party enters the election year with such narrow House and Senate margins. Yet few expect any possible Republican revival in November to represent a lasting turn of the wheel. All of the students and practitioners of politics I spoke with were skeptical that either side is positioned to end this volatility and restore anything like the extended one-party control in Washington common from 1896 to 1968.

Green, like many Democrats, believes that the small-state bias in the Electoral College and the Senate unfairly provides the GOP an edge in that competition. “It just speaks to a very rigged playing field that skews toward Whiter, more sparsely populated states and denies the will of the people,” he says.

Shor, the Democratic data analyst, agrees Democrats face long odds of controlling the Senate in particular for any extended period unless the party can win more small rural states. Still, Shor says, the pattern of midterm losses for the president’s party is so strong that even if Republicans recapture Congress and the White House in 2024, he would give Democrats about 60% odds of taking the House, and quickly shattering the GOP governing trifecta, in 2026.

Buck, the former GOP leadership aide, arrived on Capitol Hill in 2006, just before the GOP lost the House majority it had won in 1994. “My entire experience has been the seesaw of majorities,” he says. Like many other analysts, he believes the inability of either side to sustain unified control “contributes to our polarization” by encouraging the parties to use their brief windows in power to advance the highest priorities of their base supporters – thus provoking a bigger backlash from the other side. But the fleeting nature of unified control, he adds, “is also circular because it’s driven by our polarization,” in particular the widening electoral divide between red and blue America that prevents either side from establishing secure congressional majorities.

In other words, the system’s tilt away from unified control is now both a cause and effect of polarization. “I don’t know,” Buck says, “how we get off that merry-go-round.”