An 8-year-old sobs every night after her aunt puts her to bed.

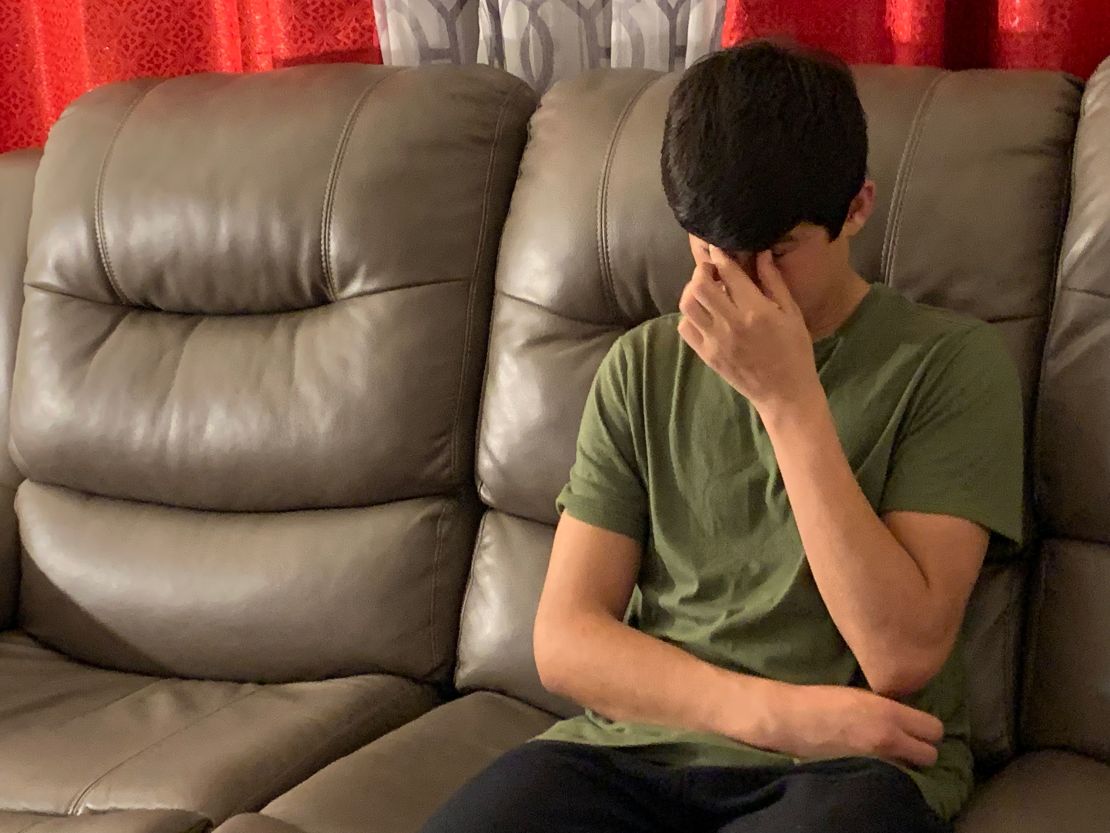

A 17-year-old wakes up clutching his pillow and calling out his little brother’s name.

And hundreds of children who remain in US government custody keep asking questions no one knows how to answer.

They’re among the roughly 1,450 Afghan children who’ve been evacuated to the United States without their parents since August.

Months after they arrived, it’s unclear when, how – or even if – some of their families will be able to reunite.

The large number, first reported by Reuters and updated in recent figures CNN obtained from the Office of Refugee Resettlement, reveals a devastating reality of the evacuations and their aftermath.

“It’s shocking…the idea that there are over 1,000 kids without their family right now, and that they’re potentially feeling alone and feeling scared,” says Dr. Sabrina Perrino, an Afghan American pediatrician in California who is hoping to become a foster parent to help.

Many of the children tried to flee Afghanistan with their families but got separated in the chaos, advocates say. Some lost touch with their parents during the bombing at Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport. And some of their parents didn’t survive the terror attack.

Officials say the vast majority of the 1,450 children who were brought to the United States without their parents were quickly released to live with sponsors – including other family members they fled with or relatives who were already living in the United States. Some were reunited with family via an expedited screening process the Biden administration created for the Afghan children.

But about 250 of the children remain in US government custody, according to statistics the Office of Refugee Resettlement recently provided to CNN. And most of those children, advocates say, have no family members to reunite with in the United States.

Families and advocates who spoke with CNN said the children, already traumatized by what they went through in Afghanistan, now are living in limbo and desperate for answers about what’s next.

Video calls with their parents are a lifeline

Two teenage boys sit on a sofa in a living roomin Northern Virginia, looking lost.

Ramin, 17, and Emal, 16, weren’t supposed to come to the United States without their parents.

The close friends, who CNN is only identifying by their first names to protect their families’ safety, were neighbors in Kabul. Together, they tried to flee the country with their families in August. But they got separated in the airport attack. Only the boys and an uncle made it out. Their parents and siblings remained behind.

When Ramin got to the United States in September, he was frantic, says Wida Amir, a board member of the Afghan-American Foundation who met him when she was helping translate for evacuees who’d recently arrived.

“He was like, ‘Take me back – send me back,’” Amir recalls.

Fear for his parents’ and siblings’ safety overwhelmed Ramin. Back in Kabul, he’d been so close with his 18-month-old little brother – they’d been spending almost 24 hours a day together – he couldn’t imagine living apart.

One night, at the Virginia shelter where he and Emal were taken after their arrival, Ramin woke up clutching his pillow like a baby and calling his brother’s name.

After spending more than a month at the shelter, the boys are now living with Emal’s uncle and his family, who came to the US nearly five years ago on a special immigrant visa after working with USAID in Afghanistan.

The teens have started attending high school and say they’re trying to focus on building a new life in the United States. They’re grateful for the chance to live in safety. But adjusting has been hard, knowing their families in Afghanistan are still in danger.

They talk with their parents nearly every day. The first video calls were difficult.

“Everyone was in tears. We just looked at each other. It was hard to have a conversation,” Emal says through an interpreter. Now, he says, those calls keep him going.

“If I don’t talk to them or see their faces,” he says, “I can’t sleep.”

The teens say they want to reunite with their parents and siblings in the United States. But their family isn’t sure where to turn to make that happen.

“It’s something I’m always hoping and wishing for,” Emal says.

There’s a ‘huge question’ that hasn’t been answered

Advocates who spoke with CNN say the procedures for reunifications with parents who remain in Afghanistan or other countries remain unclear.

“Whose job is it to reunite the parent and child, and then where do you do that?…That’s a huge question that we’re grappling with,” says Jennifer Podkul, vice president of policy and advocacy for Kids in Need of Defense, an organization that helps unaccompanied immigrant and refugee children.

The Department of Health and Human Services says the government is doing everything it can to help reunite unaccompanied Afghan minors with caregivers, including parents and immediate family, who remain in Afghanistan. But leaving the country remains a significant challenge, the agency said, describing the reunification process as difficult and noting it could take considerable time.

The Department of Homeland Security and the State Department haven’t responded to CNN’s questions about the process for these family reunifications.

Secretary of State Anthony Blinken met with a group of unaccompanied Afghan children in September when he toured the Ramstein Air Base in Germany. According to NPR, he told the group that Americans were looking forward to welcoming them, and that the US would try to help their families and friends who remained in Afghanistan.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not specify how many of the 1,450 children brought to the United States as unaccompanied minors have been reunited with their parents or how many have parents who remain in Afghanistan – two figures that CNN requested.

Officials have noted that the number of Afghan children who remain in custody is a small fraction of the total number of Afghans who were evacuated to the United States.

But what happens to those children should still be a top concern, says Ashley Huebner, associate director of legal services at the National Immigrant Justice Center.

“It’s been really difficult,” she says. “There’s a lot of frustration…with the lack of information, the lack of movement, just the real lack of urgency that we’re feeling from the Office of Refugee Resettlement and others about what is going to happen to these children, and why things are taking so long.”

Some children have trouble eating, knowing their families are hungry

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services said its Office of Refugee Resettlement takes the safety and wellbeing of children in its care “very seriously.”

“ORR’s mission is to ensure that children in ORR care are safe, healthy, and unified with family members or other suitable sponsors as quickly and safely as possible,” the spokesperson said.

Advocates who’ve spoken with the children who remain in government custody say many of them are struggling to deal with being separated from their parents, and struggling to cope with the trauma they endured before fleeing Afghanistan.

Every time Sima Quraishi visits a shelter that’s housing Afghan children in Chicago, the kids tell her how much they miss their families.

“They say, ‘You look like mom.’ They hug me. And they talk about their parents,” says Quraishi, head of the Muslim Women’s Resource Center.

When she looks at the children, Quraishi says she sees herself. She was born in Afghanistan and came to the United States as an orphan more than 30 years ago. And she’s trying to encourage the kids and give them hope. But it’s hard, she says.

“There’s a lot of support from the government that they want to make sure that they find their families. But how long will it take? None of us know,” Quraishi says. “We don’t even know what’s going to happen to these kids.”

At the Starr Commonwealth Emergency Intake Site in Albion, Michigan, Afghan children have been telling attorneys how worried they are for months, says Jennifer Vanegas of the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, whose team has spoken with children detained at the shelter.

“It’s heart wrenching. Many of their families are in hiding, don’t have sufficient food, don’t have a way to get out. … We’ve had children tell us they are having trouble eating because they know their families are hungry,” she says.

The roughly two dozen Afghan minors at Bethany Christian Services’ facilities in Michigan and Pennsylvania are constantly asking what can be done to help their families, says Nathan Bult, the organization’s senior vice president of public and government affairs.

“Some of these children know that their parents are no longer alive. I think a greater number really don’t know. And we don’t know. And I don’t think the US government knows. And that’s the hardest thing to tell a child sometimes, the honest truth – we don’t know.”

Other kids have managed to connect with friends or family on WhatsApp – but that doesn’t make the situation any easier.

“They know where their parents are, and their parents are saying, ‘We’re not safe,’ and they’re trying to escape the Taliban. Between the fear of the unknown, and the fear of what they do know and can do nothing about, it’s like a constant adverse childhood experience,” Bult says, using the term experts use to describe traumatic circumstances that affect children.

“My hope and prayer is that all of these children would be able to be reunited with their extended family or their immediate family, but knowing what we know about their histories, there are some children who are never going to reunited with family,” Bult says.

And each moment the kids remain in government custody could compound the trauma they have to deal with, says Perrino, a pediatrician in San Diego and board member of the national Afghan-American Community Organization.

That’s one reason so many Afghan Americans want to become foster parents, she says. Perrino is one of them.

But the process to become a foster parent is extensive and lengthy – and so far, most of the Afghan families who’ve signed up haven’t yet qualified, Perrino says.

While she works on getting the paperwork together, Perrino has been telling her two kids about the situation.

“We’ve talked about how there are kids who don’t have their family, and that we want them to come to our house,” she says. “I try to explain to them that until these kids get to find their families, that we can still help them feel like kids, and just play and have fun.”

An aunt says the support she gives will never be enough

Even children who are living with family members are having a hard time.

Ferishta sees the pain on her niece and nephew’s faces every day. They’re living with her in Virginia now, but their minds are thousands of miles away.

Mina, 8, and Ahmad Faisal, 13, tried to flee Afghanistan with their parents and older brother. But the airport bombing tore their family apart.

The children made it to America in September, helped by a neighbor who led them to safety. But their mother died in the blast, and the rest of their family was left behind, Ferishta says.

The children were wounded in the attack, which killed more than 170 people and injured at least 200 others. For months, family members had been afraid to tell them about their mother’s death. The children learned only recently, Ferishta says, and their devastation deepened. Mina keeps asking questions her aunt doesn’t know how to answer.

Why were she and her brother flown to Germany after the attack and treated there? Why couldn’t her mom come, too? When will her dad arrive?

“Every night she starts crying until she goes to sleep,” Ferishta says, “and sometimes it’s so hard for her to stop.”

Ferishta does her best to comfort her. But now more than ever, Ferishta says, the children need their father by their side. They’ve already been through so much. They endured treatment for their injuries at Landstuhl hospital in Germany and Walter Reed Army Medical Center outside Washington. Then they spent 20 days at a Virginia shelter for unaccompanied minors while Ferishta frantically tried to get them out. And now, they’re grieving their mother’s death as they try to adjust to their new life in America.

Ferishta says in many ways, they are the lucky ones. If the neighbor who helped them hadn’t gotten in touch with Mina and Faisal’s parents, their family would likely still be searching for them.

The children’s names and birth dates are wrong on all the official documents issued during their journey – a problem she imagines is common for many of the Afghan children who were evacuated without their parents. That, she fears, means families searching for loved ones might not be able to find each other.

Ferishta knows her family’s story is just one of many. Reuniting separated Afghan families should be the government’s first priority, she says.

“All those children who made it here without parents,” she says, “I can feel them, every day that I am living with my niece and nephew, how much they are suffering.”

CNN’s Jennifer Hansler contributed to this report.