Four years ago, Republicans and Democrats in Florida were similarly optimistic about their chances of winning the governor’s mansion and a toss-up race for a US Senate seat during the 2018 midterms. The results of those races – razor-thin victories for Republicans in both contests – devastated Democrats but nevertheless seemed to reenforce Florida’s status as a purple state.

But as the calendar turns to 2022, doubts are creeping in, as Republican momentum and Democratic malaise have many seeing a deeper shade of red here.

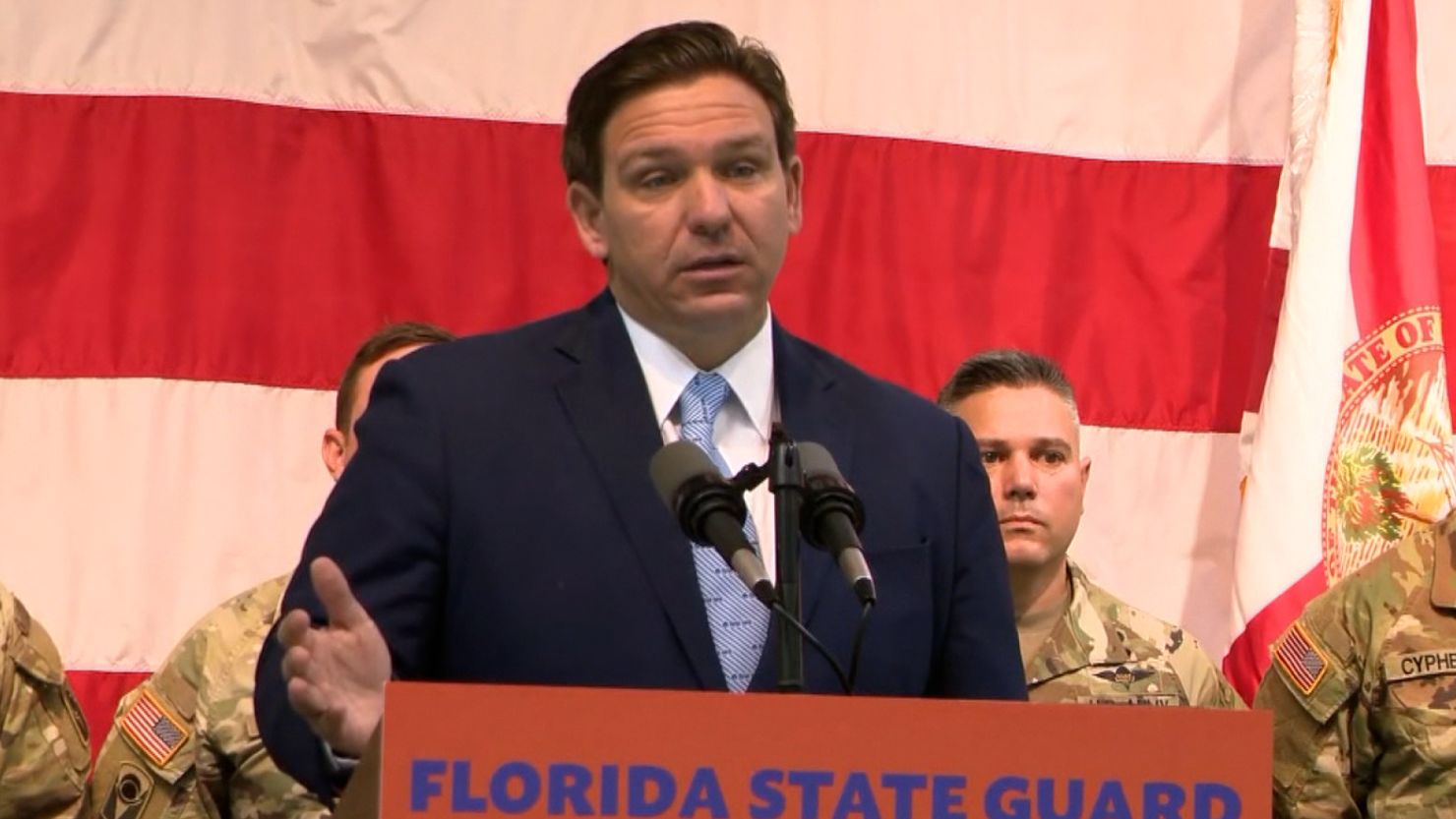

On the back of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ aggressive governing style and national appeal among conservatives, Florida Republicans have built a media and fundraising juggernaut that Democrats have struggled to match. For the first time in modern history, there are more active registered Republican voters in the state than Democrats – a shift in political winds that began with Donald Trump’s presidency and continued under DeSantis. And total GOP control of state government in Tallahassee has given Republicans the freedom to set the agenda for the election year, unilaterally change voting laws and draw new congressional maps that could swing the US House their way.

With this momentum, Republicans are not only looking to defend DeSantis and the seat held by Sen. Marco Rubio next year, but they also hope to take Florida – the quadrennial prized swing state – off the electoral map in the 2024 presidential election cycle.

“We don’t want to just win in 2022, we want to completely dominate at the federal, state and local levels so (national Democrats) decide to go elsewhere in future elections,” said Joe Gruters, the chairman of the Republican Party of Florida. “We don’t want to be a purple state. We want to make a statement that Florida is red.”

The Florida Democratic Party, meanwhile, faces an uphill climb in trying to recover from its 2020 losses. Financial woes and lackluster fundraising have put the party at a disadvantage in a notoriously expensive state to campaign in. Voter registration, once a bright spot for the Democrats, has floundered, and the party is hemorrhaging Hispanic support.

The result: The opportunity for Democrats to knock off DeSantis, perhaps the biggest star in the post-Trump GOP and a 2024 contender, and Rubio, a past presidential hopeful who still harbors White House aspirations, is off to an uneven start. And there is still an eight-month race primary ahead among three candidates to determine who will face DeSantis. Rubio’s likely opponent is US Rep. Val Demings.

“There’s a lot of opportunity in Florida, but we have to get the fundamentals of winning, which is voter registration and messaging, before we get to a path to victory,” said Ashley Walker, a veteran Democratic strategist based in South Florida.

The growing chasm between the two parties has some Democrats bracing for national donors and party operatives to look elsewhere when it comes time to divvy up resources, with consequences that could reach beyond next November.

“If we don’t turn this around, it may be the start of donors not viewing Florida as a swing state,” said Justin Day, a top Democratic fundraiser in Tampa. “Republicans have the ability this cycle to shut the door.”

Florida Democratic Party Chairman Manny Diaz acknowledged he has confronted this chatter from donors. His stock response is to point out that winning Florida’s 30 Electoral College votes is a game ender, while “less than 44,000 votes in 2020 between Georgia, Arizona and Wisconsin kept us from an Electoral College tie.”

“So when I hear that from donors, I say, ‘Really? You’re going to put all your eggs in that basket and hope that those margins remain?’ ” Diaz said. “That’s a risky proposition.”

Key gubernatorial and Senate races

Last month, the Democratic Governors Association attempted to beat back a report from Politico that the organization was planning to defend vulnerable incumbent governors in states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania rather than enter an expensive fight against DeSantis. The association had pumped $15 million into Florida in the previous two election cycles.

“Florida is a competitive battleground state in 2022,” Executive Director Noam Lee said in a statement. “Gov. DeSantis is vulnerable and defeating him is a priority for the DGA.” Lee declined to say in the statement how much the party will spend.

Yet it’s undeniable that Florida Democrats are at a significant fundraising disadvantage heading into the midterms. Eleven months before the election, DeSantis has more money on hand, $68 million, than he raised in the entirety of his 2018 campaign. His would-be Democratic competitors – US Rep. Charlie Crist, Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried and state Sen. Annette Taddeo — have $7.5 million among the three of them.

In her Senate bid, Demings has fared better, raising $13.5 million through September, including an impressive $8.4 million haul in her first full quarter as a candidate. The Orlando congresswoman has leveraged her time in the spotlight as a Trump impeachment manager to build a national fundraising network that has quickly rivaled Rubio’s.

While Democrats are undecided on their pool of gubernatorial candidates, there is enthusiasm surrounding Demings. Democrats believe that Demings, a Black woman and former police chief, has unique star power. And her background makes it difficult for Rubio to run the GOP playbook of linking Democrats to socialists, though he is trying. In a statement, Rubio’s campaign called the President’s $1.75 trillion economic and climate package, which Demings voted for, “Biden’s Build Back Socialist agenda.”

But some Democrats worry that Demings will suffer the same fate as other promising candidates if the party doesn’t get its act together.

“She’s an amazing candidate with a great personal story and I believe the race will be close, but she can’t do it without party infrastructure in a state this big,” Day said. “Instead of focusing all her time on campaigning and getting her message out, she has to register the voters and build the infrastructure. This is the basic blocking and tackling that the party should be performing, and I don’t see that support there yet.”

Diaz, a former Miami mayor, insists the work is being done since he took over the party earlier this year. He retired the party’s outstanding debt and said he is building an apparatus that will engage with voters year-round – though his successors have made similar promises.

“We’re not going to be outworked, I can tell you that,” Diaz said.

Unclear still is how involved traditional Democratic donors will be in Florida. Through a spokesman, Donald Sussman, a Democratic mega-donor who gave $1.5 million to DeSantis’ 2018 opponent, Andrew Gillum, declined to discuss whether he will support the party’s nominee in Florida this time around. Another top donor, the labor union American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, didn’t respond to requests for comment about its intentions in 2022. The organization gave Gillum $1.5 million in 2018 after he was named the Democratic nominee.

Across the country, it’s expected to be a challenging midterm election for President Joe Biden’s party. First-term presidents traditionally face losses in Congress and statehouses, and the steady decline in Biden’s approval rating suggests Democrats will have to be tactical in deciding which races to focus on.

Florida Democrats were already contending for dollars against states with hotly contested gubernatorial races like Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Kansas, among others. More competition recently arose with the decision by Massachusetts’ popular Republican Gov. Charlie Baker to not seek another term and Stacey Abrams’ entrance into the Georgia governor’s race.

Fried said it’s silly to dismiss Democrats in a state that had three statewide races so close in 2018 they triggered recounts, including her own. She said Democrats should be lining up to halt DeSantis’ path to the White House in 2024.

“We are ground zero for the culture war and the radicalization of the Republican Party, and the entire country needs to be here in Florida,” Fried said. “If we want to win in other states, we need to win first in Florida.”

Lessons learned

The election results last month in Virginia and New Jersey should be a “wake-up call” to Florida Democrats, said John Morgan, an Orlando personal injury attorney who has cut six-figure checks in the past to Democratic candidates and has bankrolled successful campaigns to raise the minimum wage and legalize medical marijuana in Florida. The Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Virginia, Terry McAuliffe, lost to Glenn Youngkin, while New Jersey’s Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy only narrowly eked out a victory in a state Biden had won by 16 percentage points the previous year.

They had attempted to tie their opponents to Trump. They also frequently invoked DeSantis, insisting that Republicans, if elected, would follow the Florida leader’s lax coronavirus policies. At the time, the Sunshine State was the epicenter of the country’s outbreak and on its way to 60,000 Covid-19 deaths.

“The Democratic Party has so many self-inflicted wounds,” said Morgan, a Crist supporter in 2022. “Republicans get to sit back and watch the dumpster fire.”

Christian Ulvert, a Democratic strategist advising Taddeo, said his party cannot run a campaign about Trump in 2022, even if he is living in the state. He said Democrats must invite parents to have a voice in their kids’ education. McAuliffe faced blowback in his race for declaring, “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.”

“Voters are tired of litigating the past,” Ulvert said. “They want to see what tomorrow is going to look like. Virginia, hopefully, taught Democrats not to focus on yesterday; focus on tomorrow.”

But Democratic operatives in Florida said they’re not seeing a consistent message so far. The gubernatorial candidates have likened DeSantis to a dictator for banning businesses, schools and governments from enforcing mask mandates or requiring workers to get vaccinated. DeSantis has contended that Florida is more free than any other state. His campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Nor do Democrats yet have an answer for the free airtime DeSantis receives, especially on conservative outlets. Several times a week, DeSantis lands the state plane in a different part of Florida, where he attracts local cameras and sometimes gets national airtime for his latest declarations. This week, he invoked Martin Luther King Jr. and he introduced legislation allowing parents to sue schools that teach critical race theory, earning him local headlines, glowing coverage from conservative outlets and outrage from left-leaning pundits.

“The governor is in a great spot,” said Joanna Rodriguez with the Republican Governors Association. “He’s doing a good job focusing on Florida, keeping his head down, ignoring the national noise about 2024. He’s making his way around the state and getting into as many markets as possible and letting people see him in their communities.”