Nicole began her morning with a simple prayer: “Please let my car start today.”

She had already gotten the mandatory ultrasound, scrounged up $595 and taken time off work. But at that moment – with her pregnancy at exactly six weeks – getting an abortion in her home state boiled down to her hatchback’s temperamental engine turning over.

On that Friday morning in early October, as heavy rains and flash floods swept through Houston, Nicole was cornered into making a painful decision on a hairline timeframe. She was one of thousands of Texas women feeling the impact of a new state law banning abortions after embryonic cardiac activity is detected, usually around six weeks of pregnancy – often before a woman even realizes she is pregnant.

As the clock ticked away, with what felt like the world working against her, Nicole finally got her car to start. Soon, she ran across a wet parking lot into Aaron Women’s Clinic for her morning appointment.

If she’d had more time to think, she said, she may not have gotten the abortion at all. But without the flexibility to plan her future, or the resources to go to another state for the procedure, the mother of two said she made the best decision she could in the limited window she was afforded.

“I just had to honestly just make the decision quickly and say you know what, I’m 33 years old, I have a week and a half to kind of decide this, and it’s just going to be a ‘yes,’ honestly, at this point,” Nicole, who asked that her last name not be used, told CNN minutes before having the procedure.

As Texas’ law hurtles toward the US Supreme Court, women in Nicole’s shoes have been forced to make rushed decisions or travel hundreds of miles to access health care. The choice presents women with a staggering list of logistical challenges, including what to do about child care, how to cover the cost of travel and whether they can miss work – which, for many women, prove insurmountable. The restrictions not only control where women can receive abortions, but also impact both the type and timeliness of the procedure. And, for some, it means not receiving care at all.

The struggle transcends Texas. A wave of restrictive abortion laws is moving through legislatures across the United States, increasing barriers and mileage between women and abortion providers.

What’s more, some legal experts say there is a very real possibility that by next year, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court could overturn Roe v. Wade – the 1973 landmark decision that affirmed the constitutional right to abortion nearly a half-century ago. To do so would trigger abortion bans across a vast swath of the country and, in essence, strip away a constitutional right that has protected women’s choice for an entire generation.

As law professor Joanna Grossman put it, “It’s just a really scary time to be a woman.”

‘They are just in panic mode’

At Aaron Women’s Clinic – an abortion facility sandwiched between a pair of auto shops in north Houston that has been in business since a year before Roe v. Wade – Linda Shafer, the clinic administrator, peered into the beige waiting room. Small paintings of flowers hung on either side of 11 empty chairs, bringing a little burst of color to the otherwise drab room, where the blinds were fully drawn. Nicole barely kept her appointment that morning, but five others missed theirs.

Maybe it was the flash floods, maybe they couldn’t come up with the money in time, or maybe they just changed their minds. Regardless, rescheduling would not be an option. Shafer clutched the gold cross around her neck, knowing that come Monday, all five women would be too far into their pregnancies for the doctors at her clinic to help – and, if they still needed abortion providers, she would have to tell them to go out of state.

In her 22 years at the clinic, she’d borne witness to change after change in the state’s abortion laws – with restrictions steadily chipping away at her ability to serve patients. At this point, she said, women seeking abortions are often in tears while she’s resigned to a sense of helplessness.

Around the six-week mark, the patients “don’t know where to go, they don’t know what to do, they don’t have the funds,” she said. “They are just in panic mode.”

The new law has dramatically transformed Texas women’s access to abortion into an hourslong odyssey across state lines. Before the ban went into effect, women of reproductive age in the state – between 15 and 49 years old – had to drive a median distance of roughly 19 miles to the nearest abortion clinic, according to a CNN analysis. Now that Texas clinics are turning most pregnant women away, they are forced to drive a median distance of 243 miles to the nearest out-of-state clinic.

For some women in the Rio Grande Valley on the US-Mexico border, the nearest out-of-state clinic in the United States is 600 miles away, in Shreveport, Louisiana – a 10-hour journey each way.

One study examining Texas data found that a more than 200-mile increase in driving distance to the nearest abortion clinic can cut the abortion rate by as much as 44%.

“Throughout history, we have seen that patients of color, patients who live in rural areas and patients who have less economic means – they are the patients who are disproportionately affected by any barriers in health care,” said Kristina Tocce, medical director at Planned Parenthood Rocky Mountains, which includes New Mexico, Colorado and southern Nevada. “History is repeating itself,” she said.

A few organizations – including the Lilith Fund and Fund Texas Choice – help women by providing financial support for travel. But for some, that’s not enough.

“There are people who, it don’t matter how much money we give them, they can’t leave the state,” said the Rev. Katherine Ragsdale, former president of the National Abortion Federation.

For most women in Texas, the nearest providers across the border are clinics in Shreveport and Oklahoma City, according to a CNN analysis of census data and driving distances.

In September, Planned Parenthood clinics in nearby states saw more than 11 times as many patients from Texas than they had in previous years, the organization said. The only clinic in Shreveport told CNN that Texas patients now comprise 50% of its roster, up from 20% before the ban.

In search of available appointments, some patients are traveling even farther to see a provider sooner, said Emily Wales, interim president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Great Plains, which includes Oklahoma.

“They’re coming to other states, but the majority, I think, are actually waiting longer to stay closer to home,” she said.

Planned Parenthood reported seeing women from Texas at its clinics in Kansas, Colorado, Nevada and even as far as New York.

Most of the women the Aaron Women’s Clinic serves probably won’t make it out of the state, according to Shafer. She said most of her patients are from minority communities and often don’t have the resources to travel for an abortion. At the same time, she added, they can’t afford to have a baby.

All she can do sometimes, she told CNN, is pray for her patients.

“Lord, if it be your will … women need help too,” she said. “Don’t forget about us.”

Legal maneuvers leave women in limbo

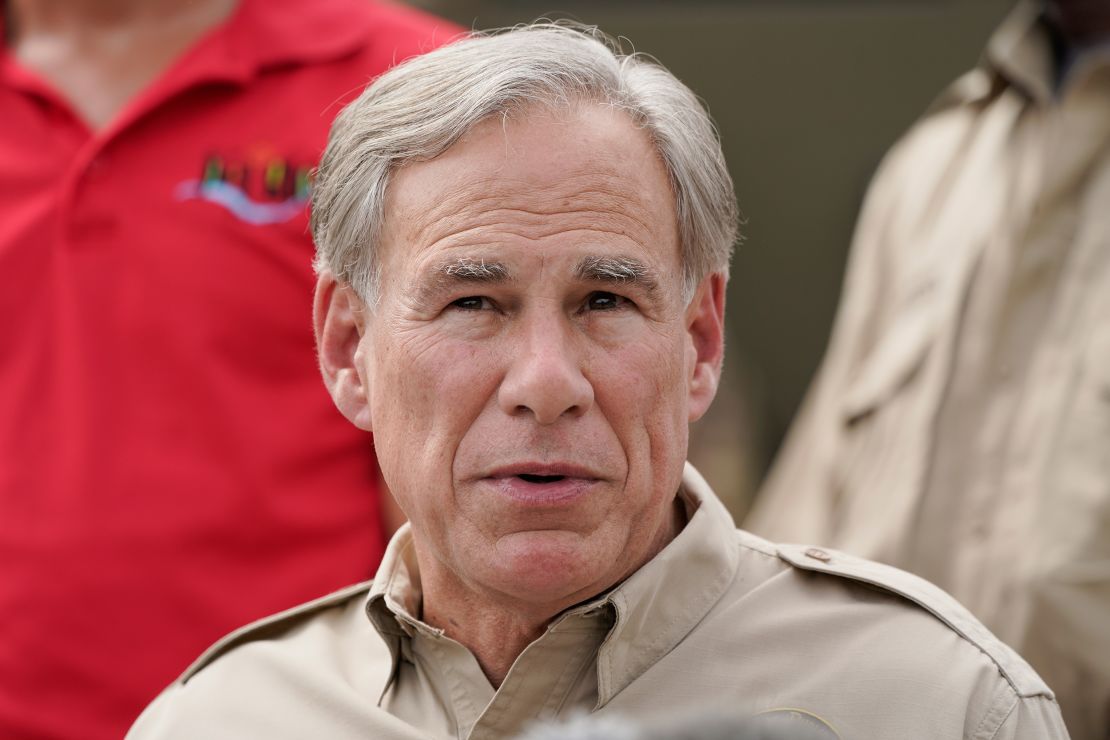

As Gov. Greg Abbott signed the new law in May, he declared that “our creator endowed us with the right to life and millions of children lose their right to life every year because of abortion,” and said the bill would “work to save those lives.”

While Abbott echoed rhetoric used by anti-abortion activists for decades, the law he signed was unprecedented: It allows private citizens to sue abortion providers, in a novel method to evade judicial review.

That has led to a series of head-spinning legal maneuvers, leaving patients and providers in the state in limbo. Polls show that while Texans are closely divided on the new bill, a majority of Americans are against it.

Just over a week after the Texas ban went into effect, the Biden administration challenged the law, after declaring that it “blatantly violates the constitutional right established under Roe v. Wade.”

A federal judge initially sided with the Department of Justice and put a temporary block on the abortion ban, but Texas appealed, and days later the appellate court signed an administrative stay, essentially letting the ban go back into effect. The DOJ unsuccessfully asked the appeals court to lift the stay late last week.

On Friday, the Supreme Court rejected a request from the Biden administration to temporarily block the law, but agreed to hear oral arguments on it on November 1.

Even during the brief temporary block, providers were hesitant to perform abortions because the new law allows for retroactive lawsuits. Aaron Women’s Clinic decided not to offer abortions past six weeks of pregnancy during the reprieve because of that legal uncertainty.

“It’s almost like you have to check the law every morning when you get up before you go to work,” Shafer said, “because you don’t know what changed overnight.”

More abortion restrictions nationwide

While neighboring states still provide a safe haven from the Texas ban, that reprieve may be short-lived.

Despite the dropping national abortion rate, a record number of abortion restrictions – 106 – have been enacted across 19 states this year, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights think tank. The previous spike came in 2011, when 89 restrictions were enacted.

A six-week abortion ban, similar to the Texas law, was set to take effect in Oklahoma on November 1 until a state judge blocked it earlier this month. The state is expected to appeal. Florida Republicans introduced a bill, modeled on the Texas law, that prohibits abortions after six weeks and uses a similar legal mechanism to allow private citizens to sue abortion providers.

A Mississippi abortion law – which bars most abortions after 15 weeks without exceptions for rape or incest – will be reviewed by the Supreme Court on December 1, giving the conservative majority on the high court an opportunity to reconsider Roe v. Wade. The court is likely to deliver its ruling on the case in June 2022.

“If you look at the current Supreme Court right now, there are six people who are on record opposed to abortion rights,” said Grossman, a law professor at Southern Methodist University, referring to the six conservative members of the court.

The fact that the justices allowed the Texas law to go into effect suggests that “they’re going to get rid of abortion no matter what,” she said.

Priscilla Smith, senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Program for the Study of Reproductive Justice, shares similar suspicions.

“There’s no reason to believe that they’re not going to do it,” said Smith, “except for the fact that they like to do things quietly” – suggesting that the court could at least undercut Roe v. Wade, if not reverse it.

If Roe v. Wade is overturned next year, 11 states – Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas and Utah – have so-called trigger laws that would immediately ban all or nearly all abortions, effectively creating a blackout for the procedure across large swaths of the country. Abortion would still be accessible in states such as New York, which passed legislation to protect abortion rights. But many women, particularly in the South, would have to travel long distances to get abortion access.

“The abortion map is just going to look like the presidential election map,” Grossman said.

Clinic closures and wait times take a toll

Abortion laws have been used as political footballs for decades, but they have immediate real-life implications for women such as Caroline, a 27-year-old Texan. She waited a month and a half for an abortion appointment more than a thousand miles away, and was 18 weeks pregnant at the time of the procedure.

The wait was devastating. As a woman living with domestic abuse and few financial resources, she said, abortion was her only option.

“A lot of women in domestic violence situations,” she told CNN, her voice cracking, “know that if they give birth, that child will be turned into a weapon.”

Caroline, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, said she agonized over her decision while waiting for her appointment at a Colorado clinic, the first to respond to her request. “I haven’t been able to sleep and eat,” she said. “Pregnancy takes a toll on your body and my body’s just been hurting.”

Pregnancy complications at 17 weeks, just a few days before her procedure, made Caroline certain about her decision.

Ten years ago, Caroline would have been able to get an abortion at 62 providers in Texas. But over the past decade, a string of restrictions has slowly chipped away at abortion access in the state, forcing facilities to shut down. In 2017, 43% of Texas women lived in counties without clinics that provided abortions, according to data from the Guttmacher Institute.

Jason Lindo, an economics professor at Texas A&M University who has studied the effects of abortion restrictions in Texas, said many of the clinics that were forced to close down after previous restrictions never reopened.

“Even if the new law is successfully challenged, it may continue to do damage,” he said.

At Aaron Women’s Clinic in Houston, that fear may become reality. With fewer patients able to come in, the clinic has already had to let go of three employees, a staff member told CNN.

“We’re at 25% patient load. If this continues, I don’t know if we’re going to remain open,” she said.

Restrictive abortion laws shuttering clinics across the country have forced a growing number of women to leave their states for the procedure. In New Mexico, for example, about a fourth of abortions in 2018 were performed for out-of-state residents – one of the highest rates in the United States and a nearly fivefold increase from the 2009 rate, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Clinic closures in one state often lead to busier clinics in neighboring states. In 2018, Texas, the second-most populous state in the country, performed more abortions after six weeks than all its bordering states combined, according to the CDC data – procedures that clinics in Louisiana, New Mexico and Oklahoma are likely to inherit following the latest ban.

Some clinics have been able to increase staffing to help with the recent influx of patients, but even so, providers in New Mexico and Nevada have wait times just under three weeks and Planned Parenthood in Oklahoma is booking appointments for up to four weeks out.

When women need abortion care, Tocce, the medical director at Planned Parenthood, said, even a two-week wait is an “eternity.”

‘A very realistic fear’ for the future

Tucked into the third floor of a sleek, black office building in Houston – just a few miles south of Aaron Women’s Clinic – sits Houston Women’s Reproductive Services. It opened in 2019, a few years after the Supreme Court ruled that two provisions of an earlier Texas abortion law – which led to a wave of abortion clinic closures – were unconstitutional.

Here, the nearly all-female staff affectionately refer to their clinic as “Ruth,” in honor of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a staunch defender of abortion rights who died last year. One staff member, wearing a necklace resembling one of Ginsburg’s famous collars, pulled up a pant leg to flash her RBG socks at visitors.

Still, amid the cheerful phone greetings and comforting smiles with patients, there was an undercurrent of concern about the future of “Ruth” and its patients.

“How did we get here?” asked Kitty, who has worked in abortion care since the early 1970s and now helps women at the Houston clinic navigate their options through the increasingly restrictive abortion laws in their state. “I feel like we’re on a conveyor belt going backwards.” She asked that her last name not be used in order to protect her family’s privacy.

As abortion rights are diminished, experts warn, women will increasingly have to seek alternatives beyond traditional clinics.

When Abbott’s executive order last year temporarily ruled abortions to be non-essential procedures during the Covid-19 pandemic, Aid Access, a telemedicine service, saw demand for abortion medication by mail in Texas nearly double.

That’s likely to happen again because of the new ban, said University of Texas professor Abigail Aiken, who is studying the impact of the law. Cost and clinic proximity, she explained, motivate women to consider telemedicine and abortion medication by mail.

Although a new law set to take effect in December bans the mailing of abortion pills in Texas, Aid Access provider Christie Pitney said this won’t stop the organization from delivering the medication to those in the state requesting them. The organization, which has clashed with US regulators in the past, is headquartered in Austria, and Rebecca Gomperts, Aid Access’ founder and the doctor prescribing the pills to patients in Texas, is licensed in Europe.

“I think we’ll have to see what happens,” said Pitney, “but I believe that (Gomperts) being based out of Europe kind of gives her a cushion and protection there.”

While Food and Drug Administration rules require women to receive abortion medication from a medical provider in person, the agency has declined to enforce the policy during the Covid-19 pandemic, citing a scientific review of clinical outcomes and adverse effects of abortion medication.

The World Health Organization deems abortion medication safe for at-home use up to 12 weeks of pregnancy without the supervision of a medical provider.

Still, with options for abortions dwindling, some medical providers fear reproductive rights in the United States could circle back to pre-Roe days – when more dangerous methods of self-managed abortions and unregulated providers were commonplace.

“We have seen that when patients aren’t able to access safe, legal abortion, that doesn’t stop abortion from happening,” said Tocce. “Will patients be attempting to self-abort or utilize unsafe means? I think that is a very realistic fear.”

In Houston, a finicky car that finally bothered to start saved Nicole from going back to square one – debating options that would have grown more limited as the hours wore on.

“I don’t know what would have been my next options,” she told CNN in the minutes before her appointment. “I’m just grateful that my car came on today.”

That afternoon, after her appointment at Aaron Women’s Clinic, a nurse gingerly walked Nicole out of the front door and into the drizzly parking lot, where her car was waiting for the drive home.

Methodology

To find the median driving distance to abortion clinics for Texas women of reproductive age, CNN used data on age and sex from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey. For each census tract in Texas, CNN found the abortion clinic closest to the center of the tract and calculated the driving distance using an application programming interface from Google Maps.

In analyzing CDC data on out-of-state abortions, CNN excluded abortions if it was unknown whether a patient traveled out of state or had the procedure in her home state.