Smoke from wildfires impacts far more people east of the Rocky Mountains than in the West, where most large fires ignite, according to a recent study published in the journal GeoHealth.

Epidemiologists at Colorado State University estimated that long-term exposure to wildfire smoke leads to roughly 6,300 additional deaths each year, with the highest numbers found in the most populous states. Out of those extra deaths, 1,700 occurred in the West.

Katelyn O’Dell, lead author of the study and postdoctoral research scientist at George Washington University, told CNN that though that difference is due in part to higher population in the East, it shows that “smoke is not just a Western problem.”

“It has real health implications for those in the East as well,” O’Dell said. “This smoke can travel from large, distant wildfires or could be from smaller local fires.”

Wildfire smoke carries fine particulate matter, or PM 2.5, a tiny but dangerous pollutant. When inhaled, it travels deep into lung tissue, where it can enter the bloodstream. PM 2.5, which comes from sources such as smoke, fossil fuel plants and cars, is linked to a number of health complications including asthma, heart disease, chronic bronchitis and other respiratory illnesses.

Researchers analyzed the number of asthma emergency room visits and hospitalizations resulting from smoke-related PM 2.5 across the country from 2006 to 2018 and found that, while the Eastern United States generally experiences lower smoke concentrations than the West, it still has a higher population density, meaning more people are exposed. During that time, there was a higher number of PM 2.5-related emergency room visits overall, they found.

Although the study didn’t measure recent fire years, O’Dell said 2020 and 2021 may have been similar to – or possibly worse than – the 2017 and 2018 fire seasons, which their study showed to be particularly devastating in terms of public health risks.

In July, when the Bootleg Fire and Dixie Fire were burning in Oregon and California, the smoke wafted east to cities such as Philadelphia and New York, where the sun turned red and sunshine was blotted out as air quality plummeted to hazardous levels.

And because East Coast residents may feel far removed from what’s happening in the West Coast, O’Dell said it’s easy to ignore the health implications associated with wildfire smoke traveling past the Rocky Mountains.

“You may be unaware when you’re breathing in smoke,” O’Dell said. “It may not look or smell like smoke, just ‘hazy,’ so your eyes and nose are not the best indicators of smoke.”

Instead, O’Dell recommended paying attention to local air quality advisories, or monitoring the air quality yourself with appropriate apps, and adjust your outdoor plans if air quality is expected to be poor.

Researchers say the combined risks of wildfire smoke and ambient local pollution are an urgent health issue, particularly for society’s most vulnerable communities. The study follows a report from a coalition of environmental justice groups earlier this year that found the concentration of particle pollution in the Bronx and Brooklyn in New York is up to 20 times higher than what was recorded by the state’s air quality monitors.

Major arterial highways, bus depots, industrial facilities, power plants and other infrastructure create daily air pollution challenges for these neighborhoods, which take a cumulative toll on residents’ health that can lead to more hospitalizations and emergency room visits.

While the wildfire smoke study did not look into the specific impacts of PM 2.5 pollution in historically marginalized communities, O’Dell points out that studies have shown people of color and low-income residents are disproportionately exposed to higher concentrations of outdoor, urban air pollution.

When it comes to reducing smoke exposure, some of the factors that may contribute to the inequality “include access to air conditioning or filters, ability to relocate or remain indoors during intense smoke events, and possible language barriers with smoke or air quality warnings,” O’Dell said.

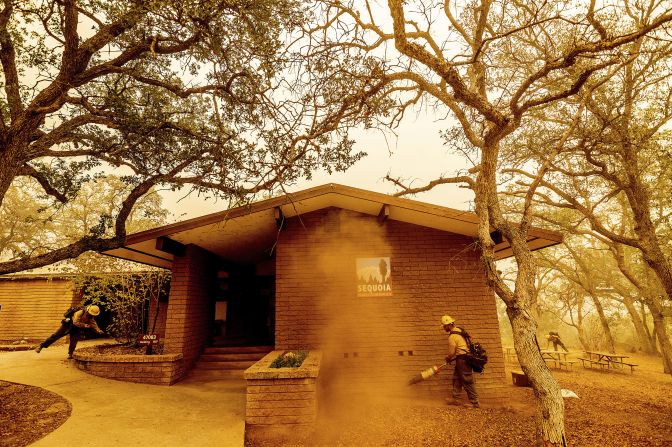

In pictures: Wildfires raging in the West

These barriers are evident in many low-income communities in New York, which experience an unequal health burden as a result of years of chronic exposure to air pollution. Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance who helped lead the local community deployment of air quality monitoring devices, said that while the study did not measure the specific impacts of wildfire smoke at the community level, historical trends show there is an underlying inequity on who gets impacted the most.

“It’s this disaster movie that those of us who’ve been doing this work for years knew was coming,” Bautista, who was not involved with the study, told CNN. “West Coast fires affecting New York City only adds to the alarm and the urgency for those of us who’ve been fighting to make sure that we’re taking (pollution-related health impacts) serious as a society.”

Tarik Benmarhnia, a climate change epidemiologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography who studies the health impacts of wildfire smoke, said the study is a significant improvement to previous wildfire research. It also opens the door to conduct further research to include temperature changes and to dive deeper into the demographics of populations impacted.

“If we compare two neighborhoods – one wealthy neighborhood in Manhattan compared to, say, the South Bronx – when a smoke comes tomorrow, we can’t assume that it will be the same problem, the same response and the same consequences,” Benmarhnia, who was not involved with the study, told CNN.

As the climate crisis intensifies, scientists say large wildfires will only intensify and increase in frequency in the coming century. O’Dell said better warning systems and monitoring air quality levels can reduce exposure and health risks.

“We will likely have more smoke in our future, but that isn’t the only source of PM 2.5,” she said. “We should aim to reduce our other PM 2.5 sources that are more controllable as much as possible (and) take action on climate change by reducing our greenhouse gas emissions to reduce the impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire intensity.”