Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

China’s growth is seriously slowing down as the country lurches from one economic threat to another. And while some of the biggest pain points appear to be easing, an unfolding crisis in real estate is emerging as one of Beijing’s toughest challenges in the coming year.

The country’s GDP grew at its slowest pace in a year last quarter, expanding just 4.9% from a year earlier. Compared to the prior quarter, the economy grew a mere 0.2% in the July-to-September period — one of the weakest quarters since China started releasing such records in 2011.

Disruptions due to the global shipping crisis and a massive energy crunch contributed to the slowdown.

Shipping delays and mounting inventories in China have hit smaller manufacturers that are now hurting for cash, resulting in lost orders and production cuts. And factory output has been dented in large part because of power shortages, a result of high demand for fossil fuel that has clashed with a national push to reduce carbon emissions.

But some of the most significant concerns for growth are now rippling through the real estate sector, which is suffering from the energy woes along with a government drive to curb excessive borrowing.

Real estate-related activities — including cement and steel production — registered steep contractions last month, as did property sales and new construction projects. That has led to reduced property investment, which contracted in September for the first time since March 2020.

On Wednesday, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that average housing prices in 70 major cities dropped slightly in October from the previous month. Goldman Sachs estimated the month-on-month drop at an annualized rate of 0.5%, the first decline since April 2015.

While the power crunch has undoubtedly weighed on the real estate sector, Beijing’s crackdown is also taking its toll. Fearing the property market had become overheated, the government last year started requiring developers to cut their debt levels. It has also pledged to tame runaway home prices.

Since then, companies like embattled conglomerate Evergrande have been grappling with major debt problems, triggering worries about the risk of contagion for the sector and the broader economy.

Beijing seems unlikely to do much to ease its tight curbs on the real estate sector, according to economists at Société Générale — “possibly because they are attributing most of the blame to the power crunch, which has now eased but is not resolved.”

“To our mind, housing is the key and there seems nothing substantial in the near term to mitigate the downtrend,” wrote the firm’s Wei Yao and Michelle Lam in a Monday report. They added that there is a “very strong consensus among policymakers that housing is at the root of China’s many structural problems.”

A real estate downturn will almost certainly continue to weigh on economic growth. Research firms and banks have already slashed their forecasts for China’s GDP this year and next, worrying that the risks of a severe, property-led slowdown are rising.

Oxford Economics, for example, cut its forecast for fourth quarter growth to 3.6% from 5%. The firm recently trimmed its 2022 GDP forecast to 5.4% from 5.8%, mostly due to concerns about the real estate sector, power shortages and Covid-19.

“Stakes are high in managing the property slowdown,” wrote Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics, in a Wednesday report. He added the “relatively large economic footprint” of the real estate sector in China — it comprises about a quarter or so of GDP — means even a gradual or “managed” slowdown would “significantly” affect the economy.

A ‘key’ challenge long-term

The housing crackdown is China’s “key long-term challenge,” according to Aidan Yao, senior emerging Asia economist with AXA Investment Managers. He downgraded his forecast for GDP growth this year to 7.9% from 8.5%, partly because of Beijing’s firm stance on controlling debt in the property market and elsewhere.Meanwhile, he sees some downside risks to his 2022 forecast of 5.5% growth.

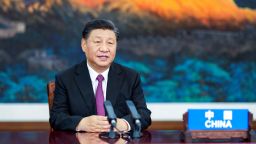

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s desire to control the housing market is no secret. In 2017, he famously announced that “housing is for living and not for speculation.”

But Beijing’s campaign has gained additional momentum during the coronavirus pandemic, as the government became concerned that too much cheap money was flooding a sector that was already highly leveraged. That worry led authorities to force developers last year to trim their debt levels.

This year, Xi has also ramped up promises to close what he sees as a worsening wealth gap, saying “common prosperity” would be a top government priority. That pledge has been reflected in tightening rules on all sorts of industries, including tech and other types of private enterprise.

But it’s also apparent in real estate, as Chinese state media outlets blame soaring housing prices for worsening income inequality.

As all of this unfolds, a liquidity crunch has worsened among the real estate sector’s weakest corporations.Evergrande — which is China’s most-indebted developer —has repeatedly missed interest payments and warned it could default.

The company’s crisis has unsettled global investors in recent weeks, who worry a bankrupt Evergrande could lead to a domino effect. Other property firms, including Fantasia Holdings and Modern Land, have already indicated they are struggling to pay their debts.

Chinese authorities have tried to assuage fears about Evergrande. The People’s Bank of China said Friday the company had mismanaged its business but risks to the financial system were “controllable.”

Yao, from AXA Investment Managers, said Beijing isn’t likely to change its course on regulation.

“Beijing’s tolerance for short-term pains from actions that foster longer-term sustainability has been a major surprise to the market anticipating a blow-out growth number for 2021,” he said. The tech crackdown, after all, has wiped more than $1 trillion off the value of major Chinese stocks worldwide, but isn’t slowing down, either.

Yao added that while there may be “further fine-tuning” of housing market policies, he sees “no reversal to the overall tightening stance.”