Shang-Chi, Marvel’s Chinese martial artist superhero, has lived many lives since his 1973 comics debut.

First, he was a “Master of Kung Fu” and assassin-turned-hero who dispatched foes with remarkable ease. He’s gone from being a version of Bruce Lee to a version of James Bond to a member of the Avengers (and sometimes, their foe). His most recent comic book iteration casts him as an employee at a bakery in San Francisco’s Chinatown, content to assemble boxes of sesame balls and pineapple buns until he’s recruited to save his estranged sister from a life of evil.

And this month, Shang-Chi is reborn yet again, this time on the big screen in “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.” Starring Simu Liu, Awkwafina and Hong Kong legend Tony Leung, it’s the first film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe with a primarily Asian cast.

With Iron Man, Steve Rogers’ Captain America and Black Widow ostensibly out of the MCU (although Loki is still alive and kicking on Disney+ despite dying multiple times), there are large vacancies to fill. It could be Shang-Chi’s turn to star in a string of billion-dollar films and endear himself to audiences.

But for many years, Shang-Chi existed on the margins of other Marvel stories. His initial series was even out of print for a while, thanks to one racist character Marvel lost the rights to use, said Steve Englehart, one of the comic book writers who created him.

From a comic that emulated kung fu films to a new series that places greater emphasis on the character’s identity as a Chinese immigrant, Shang-Chi has finally evolved into one of Marvel’s major leaguers. Get to know the many versions of the Master of Kung Fu before you meet Liu’s portrayal of the hero.

Shang-Chi’s early issues relied on some problematic stereotypes

Every iteration of Shang-Chi has a similar throughline: He’s always a spectacular martial artist, always playing tug-of-war with his former life as a fighter and always, always tormented by daddy issues. That blueprint was created by Englehart and Jim Starlin, the two-man team who brought the character to life (Englehart, perhaps best known for his dark, noir take on Batman, has also created characters like Star-Lord of “Guardians of the Galaxy,” and Starlin is responsible for MCU icons like its biggest villain, Thanos.)

In the early 1970s, Englehart and Starlin approached Detective Comics (DC) with an idea: a comic book take on the David Carradine series “Kung Fu.” (The series has been criticized for its use of “yellowface,” or casting White actors as Asian characters. Carradine is White but starred as a part-Chinese martial artist.)

Starlin, an artist, loved the martial arts element of the story, while writer Englehart said he was interested in delving into Taoism and other philosophies to flesh out his protagonist. The two thought they’d found a match with “Kung Fu” – but DC thought the “kung fu craze was going to disappear,” Starlin said, and passed on the idea.

So the pair took it next to Marvel, whose executives agreed only after insisting that the pair inject some pre-existing intellectual property into their comic, both men told CNN.

In this case, the company had the rights to the character Fu Manchu, a racist caricature of a Chinese man created by British author Sax Rohmer in the early 20th century. The villain was then “grafted onto the series” as Shang-Chi’s father, Starlin told CNN in an August interview. (Racist depictions of Asian characters had appeared in comics before this, like the egg-shaped villain “Egg Fu” in a 1965 Wonder Woman issue and the 1940 character “Ebony White” in the early comic, “The Spirit,” said Grace Gipson, an assistant professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who studies race and gender within comics.)

At the time, Englehart said, he and Starlin were instructed to make their character half White. Englehart was used to racism from comic book readers – as a writer for the character Luke Cage, he recalled some Southern stores refusing to sell issues from the series because its lead was Black – so, to get the approval they needed to write their comic, they made Shang-Chi’s mother a White American woman.

There were also the matter of coloring: Comics at the time were limited in the blends of colors they could use to produce certain shades, Starlin explained. The coloring chosen for Shang-Chi’s skin tone was predetermined, Englehart said, and ended up being an orange-yellow hue that other Asian characters in comics shared.

“Looking back, it’s embarrassing,” Starlin said of the skin tone chosen for the character. “Shang-Chi was a creation at a time when not only was there a limited outlook among a lot of folks as far as what the world was about, but we were very limited in what could be done technologically.”

Though both authors agreed to make the problematic changes to create their comic, they got to tell the rest of the story the way they wanted. Englehart wrote Shang-Chi as a cerebral, would-be philosopher contending with his violent family history and a desire to be better, while Starlin had a blast sketching complex scenes of Shang-Chi’s kung fu match-ups.

“He’s quite a moral character in a very corrupt world, much the same way that Captain America was,” Starlin said, noting Shang-Chi isn’t quite as “preachy” as the MCU’s Captain America.

“He was raised to be a perfect martial artist character, steeped in the philosophy of the East,” Englehart told CNN in an August interview. “But then he discovered that all that had been in the service of his evil father. So he rebelled against that, then was kind of making his way in the world that he didn’t understand, issue by issue, and seeing it through philosophical eyes.”

Marvel may not have expected Shang-Chi to be a smashing success – his debut was tucked into the limited series, “Special Marvel Edition #15.” It was a brief introduction to the character, covering his origins as an assassin trained by his father, a villain who used him to acquire immortality, and his realization that he’d been fighting on the wrong side, but it became a runaway hit, Englehart and Starlin said.

Soon, Marvel wanted a monthly series, an annual series, some special editions and a black-and-white version of another series that centered Shang-Chi, and Englehart and Starlin were exhausted. Churning out so much Shang-Chi content meant there wouldn’t be as much time to fully explore complex themes, at least not in the way they’d envisioned. Both departed the series after just a few issues.

“It was just so weird!” Englehart said. “We were totally into it, and nobody else was, and then everybody else was, and it became too much for us to keep up with it.”

The new ‘Shang-Chi’ series realigns the hero’s identity

Shang-Chi’s “Master of Kung Fu” series was later helmed by Doug Moench and artist Paul Gulacy, whose cinematic references to Lee and Bond won Shang-Chi new fans as the series continued into the 1980s. He appeared off-and-on in Marvel comics in the years that followed, but was never a main character in the same way he was when he debuted.

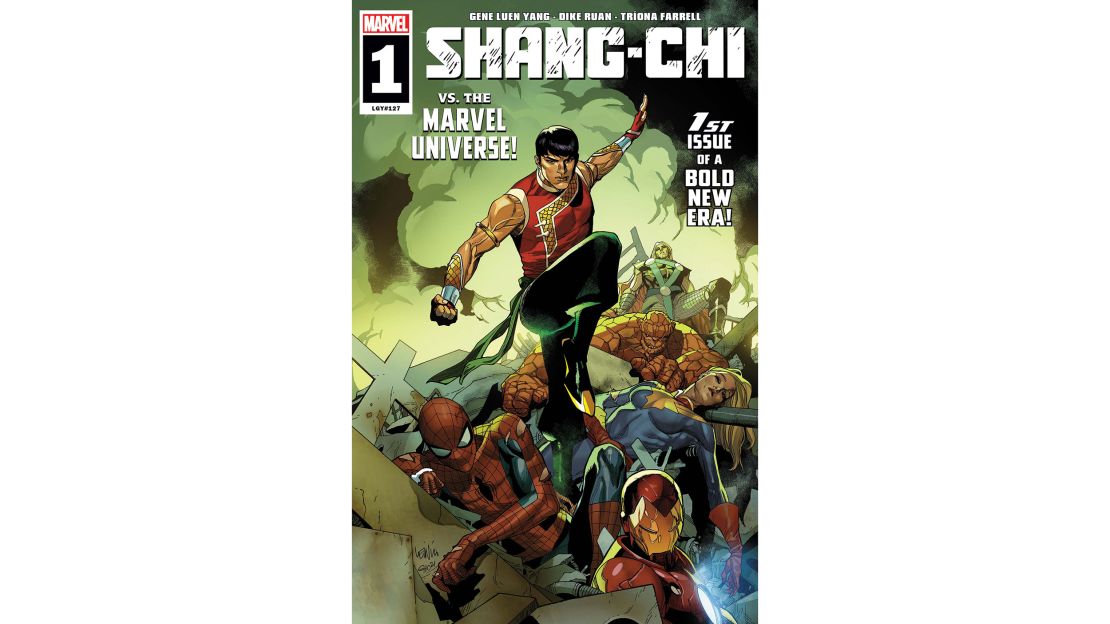

It wasn’t until 2020 that writer Gene Luen Yang was tapped to take over a new Shang-Chi series. Along with artists Dike Ruan and Philip Tan, Yang built an identity for Shang-Chi informed by his history in the comics and that of the Chinese diaspora.

Shang-Chi in his original comics run was constantly the outsider, whether he was on the streets of London working with spies or with his own family. Yang felt like an outsider himself as a young person, part of the reason why he didn’t initially connect with the character.

“I was not a Shang-Chi fan when I was a kid,” he said in a February interview on Marvel’s Voices podcast. “I encountered those Shang-Chi comics at a time when I didn’t feel comfortable being a Chinese-American. So it just felt like, you know, the Chinese-American kid picking up the comic with the Chinese superhero – it felt like I was highlighting what made me different.”

But by taking control of Shang-Chi’s comics destiny, Yang helped reshape it into a story that could have mattered to him when he was younger. That its release timing coincided with a surge in anti-Asian hate wasn’t lost on him either. In a 2020 interview with Syfy Wire, Yang said he wanted his interpretation of Shang-Chi to be a “three-dimensional hero,” to attract readers from all backgrounds and “counteract that ugliness” of anti-Asian violence and discrimination.

Yang’s version of Shang-Chi, born in China but living in California, is happily working a service job half a world away from his father, now called Zheng Zhu. He shares crystal cakes with an old frenemy and even thinks to himself at one point, “I’ve found that if I slow my cadence and use ‘wise’ words, Westerners look at me, rather than past me, when I speak.”

While Starlin and Englehart wanted to introduce concepts of kung fu and philosophy to American readers, Yang wants to show readers that Shang-Chi’s story, though it’s taken him from China to Chinatown and back again, is an inherently American one.

“Superheroes, at their best, express America at its best,” he said on the Marvel podcast. “With Shang-Chi in particular, he is an immigrant. In the original origin story, he comes as an adult, and he really finds his identity apart from his family, he finds his identity as a superhero here in America.”

Gipson, the pop culture scholar who studies race and gender within comics, said hiring writers of color like Yang to helm series about characters of color is an improvement, but it “is really not a hard task.” She said while comics creators have made great strides in deconstructing norms of who a comic book reader is and what storylines they want to see, the hiring of creators of color needs to happen consistently.

“It’s about making sure the voices of those being represented always have a seat at the table as well as a microphone to speak,” she told CNN.

Still, she said, as a fan of comics herself, she’s enjoyed seeing more representative stories being told in mainstream comics. Shang-Chi isn’t the only Asian superhero in the Marvel universe – there’s Ms. Marvel, a.k.a. Kamala Khan, a Pakistani-American teen who will soon star in her own Disney+ series and an upcoming film. Plus, Gemma Chan, Kumail Nanjiani and Don Lee will all appear in the Chloe Zhao-directed MCU film, “Eternals.” There are even more introduced in the comics, like the Arab-American teen supe Amulet and the Korean-American spider-like hero Silk.

“It gives me hope that the next generation of comic book readers and consumers can see themselves accurately depicted and portrayed on the page and the TV and film screen,” Gipson said.

That’s Yang’s goal, too, in creating a new Shang-Chi story. And now that an even newer version of Shang-Chi lives on in film, the character may finally get the recognition, and his story the same care, that his fellow Marvel heroes have long enjoyed.