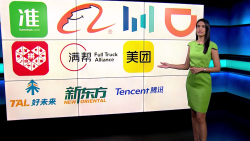

Two of China’s leading tech companies are setting up labor unions for their staff as the industry comes under intense political pressure to rethink how it treats its workers.

Chinese ride-hailing company Didi (DIDI) announced on an internal forum last month that it had established a union for its workers, according to a person familiar with the matter. The person said that the group was affiliated with the All China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), a government-backed organization under which all mainland Chinese trade unions must be registered.

This week, JD.com (JD) also created a union for employees, the e-commerce company said in a Chinese social media post Wednesday. The union, which held its first meeting on Monday, is intended to promote the “unified protection of [workers’] rights and interests, and the collective relief of challenges,” according to the company.

The move comes as China continues its historic regulatory crackdown on the tech sector, and as pressure mounts on employers to ease up on an infamous “996” working culture.

Just days ago, the country’s top court issued a lengthy condemnation of the practice of working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week, which has become known as “996” and is commonly associated with the tech industry.

In a joint statement with the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security last Thursday, the Supreme People’s Court noted that “extreme overtime work in some industries has received widespread attention.”

Workers deserve rights for “rest and vacation,” it added.

Didi and JD aren’t the only companies allowing their workers to unionize. Chinese food delivery giant Meituan also has several local unions, including one for workers in Shanghai.

All three companies say they have recently taken strides to better protect their workers. In April, for example, Didi said it set up a new committee “to protect the rights and interests of ride-hailing drivers, and stabilize [their] employment.”

Shu Sun, the CEO of Didi’s Chinese ride-hailing business, heads the committee, reporting to Didi co-founder and chairman Will Wei Cheng.

Spotlight on working conditions

Beijing turned up the heat on companies another notch this week.

On Thursday, China’s Transport Ministry said that it had summoned 11 companies, including Didi and Meituan, to warn them against recruiting unlicensed drivers and to remind them of the need to provide reasonable wages and enough time to rest.

Recently, there has been an outcry over how food and e-commerce delivery workers are treated in China —especiallyas business in those fields has boomed throughout the coronavirus pandemic, noted Aidan Chau, a researcher at Hong Kong-based group China Labour Bulletin.

It was not immediately clear whether drivers were included in Didi and JD’s new unions. Neither company responded to a request for comment. Meituan and Didi did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the ministry’s latest warning.

Chau said he believed the creation of the new unions was likely tied to recent actions by Chinese regulators.

“It has been for quite a while that society has been talking about these very intense working rhythms, working practices in the new tech sector and also the new platform economy,” he told CNN Business.

“There are increasingly small-scale protests and labor strikes in these sectors. So the union is actually one way that the [Chinese Communist] Party tries to alleviate the problems.”

Earlier this year, another Chinese e-commerce company, Pinduoduo (PDD), faced strong criticism after two of its employees unexpectedly died during the holiday season.

First, a worker in her twenties collapsed in Urumqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang region, while walking home with colleagues in December. The company confirmed her death, but did not disclose the cause.

Then, another worker died in January after jumping from his apartment in Changsha, a city in the southern Hunan province. Pinduoduo said at the time that the man had earlier asked for time off, without giving a reason.

Both cases cast attention on the issue of overwork in China and raised questions about how corporate culture should change.

Until recently, workers typically banded together more informally, such as in groups on Chinese social networks like WeChat or QQ to discuss labor conditions, according to Chau.

But “it is very difficult for workers to establish an organization with a clear structure,” he added, noting that unions often required significant resources, such as potential funding and volunteers.

— Laura He, Nectar Gan and CNN staff contributed to this article.