Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

Heavyweight global investment firms are sticking with China despite a sweeping crackdown on business by the ruling Communist Party that has wiped $3 trillion off the market value of the country’s biggest companies.

Even as authorities rip up the status quo for tech, education and other private enterprise, drawing comparisons with Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in the process, some of the biggest names in asset management say it’s still a good time to invest. They say recent regulatory moves were necessary and overdue, and China’s growth story remained attractive.

“The case for China in the long-term is intact,” said Luca Paolini, chief strategist for Pictet Asset Management. The firm is an arm of Swiss private bank Pictet Group, which has $746 billion assets under management.

Pictet isn’t alone. Many of the biggest names on Wall Street, including BlackRock (BLK), the world’s largest asset manager, Fidelity and Goldman Sachs (GS), are still advising clients to keep buying, albeit cautiously.

The “intensity” of the measures “will fluctuate,” wrote strategists at BlackRock in an August research note.“Chinese authorities will likely balance their regulatory agenda against a desire for economic stability, and the intensity of the regulatory crackdown may ease amid slower growth and market volatility.”

A broad shakedown

The clampdown over the past year has shaken many businesses to their core, and may also be acting as a drag on economic growth. The services sector contracted in August for the first time in 18 months.

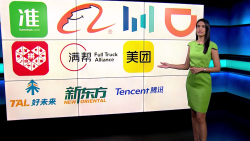

Financial tech firm Ant Group is reportedly worth half what it was before a planned public offering was shelved last November and it was forced to overhaul its business. Shares in ride-hailing company Didi have failed to come close to their IPO price after Beijing began probing the company earlier this summer. And wide-ranging rules unveiled in July essentially shut down China’s $120 billion for-profit tutoring sector.

The MSCI China Index, which tracks large and mid-cap Chinese companies, has fallen more than 13% this year. By contrast, the MSCI World Index has risen more than 16%.

Some big proponents of Chinese investment — including SoftBank (SFTBF) founder Masayoshi Son — have warned that they’ll need to wait out the regulations before deciding to buy more aggressively again. Others, including Bank of America (BAC), have recommended ditching Chinese tech stocks entirely for opportunities in Australia, Japan, India and other parts of Asia.

“While we have championed China’s impressive technological advantages and achievements on a global scale for years … we think the regulatory overhang is unlikely to dissipate anytime soon,” analysts at Bank of America wrote in July.

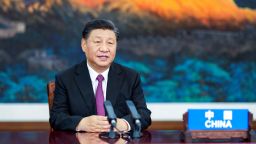

Beijing has signaled that its get-tough approach will continue for at least the next five years. President Xi Jinping has tripled down — he told government officials Monday that anti-monopoly and other measures have been necessary to achieve “common prosperity.” And state media this week widely circulated an article that first appeared on social media, which called Xi’s sweeping crackdown in economy, finance, culture and politics a “profound revolution” to end the “capitalist paradise” on China’s markets.

“Foreign investors who choose to invest in China find it remarkably difficult to recognise these risks,” billionaire investor George Soros wrote this week in the Financial Times. “Xi’s China is not the China they [investors] know.”

Soros wrote that Xi’s version of the Communist Party has acted as an “updated version” of the one helmed by Mao. “No investor has any experience of that China because there were no stock markets in Mao’s time.”

A model for the world to follow?

Pictet’s Paolini, though, isn’t worried.

By one measure, he said, the crackdown is a “belated response” to the breakneck pace at which many Chinese companies have grown and innovated. He predicted the rest of the world would follow with strict regulations on data usage and the dominance of Big Tech.

“Regulatory risk has increased, but it is now largely priced in — on our measures,” Paolini said, adding that China is the third cheapest “major” equity market and“by far the most oversold.”

BlackRock’s strategists echoed that rationale, writing that the Chinese leadership sees the measures as “necessary to rein in the industries that have been rapidly growing and lightly regulated.”

“We stand by our strategic preference for Chinese assets,” they added.

Even Goldman Sachs — which recently estimated that the crackdown had wiped out $3.1 trillion in market value for Chinese companies world wide, half of that from tech firms alone — has remained bullish.

Strategists at the investment bank wrote last week that the “uncertain trading environment” wasn’t likely tohurt the case for buying Chinese equities too much, at least not in the mainland.

Companies that list overseas may be in for a rougher time, as US and Chinese regulators alike have been squeezing firms that list in New York. Even then, though, the Goldman analysts pointed to “long-term value” for those companies — they just want to “wait for more regulation clarity” first.

China has “strong economic and earnings growth potential in a global context,” the strategists wrote.

The bankacknowledged in a July research note that stocks have taken a significant hit from the crackdown, adding that some of its clients have even asked whether Chinese markets have become “uninvestable.”

But they said they believe it’s unlikely that “extreme regulations” would spread to every sector.

The government has supported the development of “foundational technologies,” such as renewable energy and 5G networks, and “would be pragmatic when striking a balance between social/ideological goals and capital markets in non-social sensitive industries over time.”

The “indiscriminate” sell-off has also created some bargain investments for those thinking longer term, according to Victoria Mio, director of Asian Equities at Fidelity International.

“Despite policy headwinds in some sectors, China is still on track for decent GDP growth over the next decade,” she said, pointing to increasing purchasing power by the middle class.

Some firms also touted the value of other Chinese assets.

Paolini pointed out that the yuan has performed better than other major currencies this year, up 1% against the US dollar. Chinese government bonds are also overperformers, returning 3.5% compared to a 1.1% loss on JP Morgan’s global government bond index, a benchmark tracked by bond investors.

“Clearly, China remains fully ‘investable’ for foreign investors,” he added.

Caution is still needed

The Goldman analysts said, though, that any investment needs to be tactical.

Media, consumer services, education, retail, transportation and biotech could be at risk of further regulatory backlash, they added, given Beijing’s focus on solving what it sees as social or cultural issues caused by those industries.

“It’s difficult to predict the future direction of policy changes, but avoiding stocks and sectors where valuations are rich and … expectations [are high] can help mitigate this uncertainty,” said Catherine Yeung, investment director at Fidelity International. She added that investors have left internet and education stocks, instead investing in sportswear and renewables, among other industries.

“There have always been social and economic imbalances, and the pandemic has brought these to light even more,”she added.“China’s recent policy/regulation changes are set up to address these imbalances with a focus on security, autonomy and fairness.”

— Kristie Lu Stout and Jadyn Sham contributed to this article.