Hong Kong on Wednesday began the trial for the first person charged under its controversial national security law, which has transformed the city’s political landscape since it was imposed by Beijing last year.

Tong Ying-kit, 24, pleaded not guilty to two charges of inciting secession and terrorism activities after allegedly driving his motorbike into a group of police officers and injuring three at a pro-democracy protest last July.

He was allegedly carrying a banner that read “Liberate Hong Kong” at the time – grounds for inciting secession under the new law, prosecutors said.

Tong also faces an alternative charge to the terrorism count of dangerous driving causing grievous bodily harm, to which he also pleaded not guilty.

The wide-ranging security legislation, which criminalizes secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with foreign forces, was introduced on June 30, 2020, and carries with it a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

The seemingly vague parameters of the law have provided authorities with sweeping powers to crack down heavily on government opponents. Protesters and opposition leaders have been arrested under the law, while others have fled abroad in a slow exodus. The city’s highly popular anti-Beijing tabloid, Apple Daily, announced its closure Wednesday, after the paper’s assets were frozen under the national security law and several of its senior editors arrested.

Under the provisions of the law, Tong’s 15-day trial is being held without a jury, marking a significant departure from Hong Kong’s previous legal system.

Here’s what you need to know about the law – and how we got here.

What is the national security law?

The law criminalizes political dissent and offenses that challenge Beijing’s rule over semi-autonomous Hong Kong.

But the offenses are vaguely defined and wide-ranging; for instance, vandalizing public property or government premises – like protesters did in 2019 during massive demonstrations – are now considered terrorist activities.

Calling for Hong Kong independence now counts as a crime under “secession,” which is what Tong is charged with.

At court last July, Tong’s lawyer argued the interpretation and meaning of his “Liberate Hong Kong” banner is subjective, and it does not necessarily mean inciting secession or wishing to change the legal status of Hong Kong.

As the first trial under the security law, Tong’s case will be key in determining whether certain pro-democracy slogans will be deemed illegal – and will set a benchmark for how Hong Kong courts interpret the law and its provisions going forward.

The Hong Kong legal system, heavily influenced by British common law, has relied on trial by jury throughout its history. A 2003 government report noted that trial by jury was one of the “key features of the Hong Kong legal system.” But under the national security law, Beijing can take over national security cases in special circumstances – and if it involves “state secrets or public order,” it can mandate a closed-door trial with no jury.

The law also dramatically broadens the powers of local and mainland Chinese authorities to investigate, prosecute and punish dissenters, while granting mainland security agents the power to operate openly in Hong Kong for the first time.

Other provisions include the introduction of “national security education” in schools, stronger government “management” of foreign news media and NGOs, greater wiretapping abilities for police, and more.

Why is it happening now?

The national security law is not a new concept – but it was passed under unique circumstances that marked a turning point for the city.

Beijing had been asking Hong Kong to pass a national security law since the former British colony was handed back to China in 1997. But the local government backed down from its previous legislative attempts after facing fierce public opposition and protests, much to China’s frustration.

This changed in 2019. Protests over a separate bill, which would have allowed suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China, evolved into a mass pro-democracy, anti-government movement that lasted more than six months. Demonstrations often grew violent, with near-weekly clashes between protesters and police, who deployed tear gas and water cannons.

New security law sparks protests in Hong Kong

Beijing condemned the protests from afar, but largely left it to local authorities to handle – until their patience ran out. The coronavirus pandemic put a pause on the protest movement, providing Beijing the opportunity to act swiftly while people stayed home.

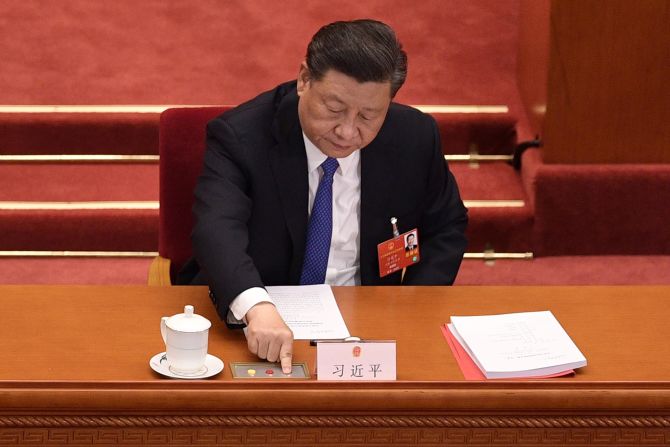

The bill was first proposed on May 22 at the National People’s Congress (NPC) and promulgated just weeks later, bypassing the local legislature.

While Hong Kong has an independent legal system, a back door in its mini-constitution allows Beijing to make laws in the city – meaning there wasn’t much the Hong Kong public or leadership could do about it.

Following its introduction, Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam has repeatedly and strenuously defended the legislation, arguing it’s main objective is to “maintain long-term stability and prosperity in Hong Kong,” and that it will target only a minority of individuals.

How has the law been used?

Police made their first arrest under the national security law the day after it was passed, and haven’t stopped since.

Last July, a dozen pro-democracy candidates were barred from standing in legislative elections on national security grounds. The following month, more than 200 police officers raided Apple Daily’s headquarters, arresting a number of top executives, including the paper’s owner, media tycoon Jimmy Lai. That same day, police arrested a prominent 23-year-old pro-democracy politician under the security law, the first of many to come.

In August, 12 Hong Kong residents – including a 16-year-old – were arrested for attempting to flee to Taiwan by boat, and detained in the mainland for months without access to lawyers. Several have since been released back to Hong Kong, where at least one was charged under the security law.

New arrests, rules and crackdown measures that would have been previously unthinkable came at a dizzying speed. Dozens of former lawmakers and opposition activists were arrested in January under the security law, and charged a month later.

Websites have since been blocked, and movies placed under revised government guidelines to abide by the law, signaling the start of a more widespread cultural censorship.

Last Thursday, 500 police officers raided Apple Daily for a second time, seizing journalists’ materials and arresting the paper’s directors. National security police then froze the company’s assets.

On Wednesday, as Tong stood trial in the city’s High Court, news broke of yet another arrest – an Apple Daily employee, followed hours later by confirmation the outlet would cease operations after June 26.

An uncertain future

The crackdown has had a chilling effect in Hong Kong, with pro-democracy figures no longer able to organize opposition, journalists facing arrest for their work, and residents fearful of what this means for the city’s future.

The mass demonstrations that characterized 2019, sometimes stretching into hundreds of thousands of participants, are nowhere to be seen. There are occasionally small flash protests, but these are quickly shut down and the organizers punished.

Hong Kong is looking increasingly like other Chinese cities, subject to Chinese laws and censorship – which throws into question its viability as a base for international businesses. Residents, too, are looking to leave – hundreds of thousands are expected to relocate to the United Kingdom, under a new scheme implemented by the UK government for holders of British National (Overseas) passports.

“I have never been so uncertain about the future in my whole life,” said Hong Kong political commentator Kim-Wah Chung in late May. He plans to stay in the city – but has been urged by friends and family to leave.

“Because of the rapidly deteriorating political situation, and some kind of uncertainty and threats, I have been warned by many people – you have to consider this,” he said.