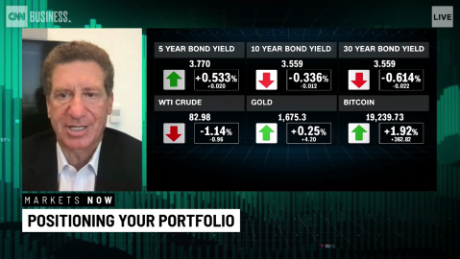

New York (CNN Business)The names of the key players are different, but the lessons similar. The spectacular implosion of hedge fund Archegos Capital Management, much like the GameStop saga earlier this year, serves as a reminder of the dangers posed by extreme leverage, secret derivatives and rock-bottom interest rates.

ViacomCBS (VIACA), Discovery (DISCA) and other media titans' stocks crashed Friday as Wall Street banks that lent to Archegos forced the firm to unwind its bets. The epic firesale wiped out more than half of Viacom's value last week alone.

Major banks face billions of dollars in losses from their exposure to Archegos. Both Credit Suisse (CS) and Nomura tumbled Monday after warning of significant hits to their earnings.

The most startling part about the tale of Archegos is that it is a firm that few people had ever heard of before this weekend. And yet in this era of easy money, Archegos was able to borrow so much that its failure created shockwaves large enough to ripple across Wall Street ŌĆö and impact everyday Americans' retirement accounts.

"It's a wake-up call. With leverage, comes risk," said Art Hogan, chief market strategist at National Securities Corporation. "This is the second time we've learned a lesson this year about leverage."

In January, another hedge fund, Melvin Capital Management, nearly collapsed after its massive bets against GameStop (GME) were blown up by an army of traders on Reddit. Investors were surprised to learn about the sheer size of the short positions anticipating the video game retailer's stock price would fall.

When GameStop shares instead went to the moon, Melvin Capital suffered staggering losses and was forced to reach a $2.8 billion bailout with larger rivals.

"We saw it on the short side when GameStop blew up. Now we are seeing it on the long side," Hogan said.

Opaque financial instruments

Archegos Capital was using borrowed money ŌĆö apparently a ton of it ŌĆö to make outsized bets that propped up media stocks. This type excessive leverage is made possible by extremely low interest rates from the Federal Reserve.

The full scale of these bets wasn't clear until now.

Perhaps in an effort to avoid making public disclosure filings, Archegos reportedly used derivatives known as total return swaps to mask some of its large investment positions. Investors using these swaps receive the total return of a stock from a dealer and those returns are typically amplified by leverage.

Archegos could not be reached for comment on Monday.

Typically, investors who own more than 5% of a stock are required to report that stake with the SEC. These filings do not appear to have been made this time.

"Anytime a derivative is involved, you don't really know how deep the tentacles go," said Joe Saluzzi, co-head of trading at Themis Trading.

The share sale that broke the camel's back

This complex strategy backfired last week.

Seeking to capitalize on its skyrocketing stock price, ViacomCBS announced plans for a $3 billion share sale. Up until that point, ViacomCBS shares had nearly tripled on the year. But the share sale appeared to be too much for the market to handle and the media boom morphed into a rout.

Archegos faced margin calls from its Wall Street lenders. A margin call by a broker requires a client to add funds to its account if the value of an asset drops below a specified level. If the client can't pay up ŌĆö and in this case Archegos apparently couldn't ŌĆö the broker can step in and dump the shares on the client's behalf.

Goldman Sachs, one of Archegos' lenders, seized collateral and sold shares on Friday, a person familiar with the matter told CNN Business. This so-called forced liquidation set off a bloodbath Friday that drove down shares of ViacomCBS and Discovery more than 25% apiece.

Credit Suisse said that the default by a "significant US-based hedge fund" would cause a major hit to its earnings. A person familiar with the matter told CNN Business that Archegos was the firm causing the losses for Credit Suisse.

Nomura said its losses could be as much as $2 billion from "transactions with a US client."

Founder of hedge fund involved in insider trading scandal

The episode demonstrates the intricate web linking firms across Wall Street ŌĆö and the risks to the banks providing large amounts of leverage.

"Systemic risk from secret and interconnected leverage, trading and derivatives in astronomical undisclosed amounts continue to permeate the shadow banking system," Better Markets CEO Dennis Kelleher said in a statement.

Hogan said investors must remember the inherent risks involved in the business lines of banks.

"They watch the creditworthiness of clients, but it's not always perfect," he said.

The creditworthiness of Archegos is a central question here. Bill Hwang, the firm's founder and a prot├®g├® of hedge fund pioneer Julian Robertson, was previously enmeshed in an insider trading scandal at Tiger Asia Management, a hedge fund he founded.

In 2012, the SEC alleged Tiger Asia made nearly $17 million in illegal profits in a scheme involving Chinese bank stocks. Hwang pleaded guilty that year on behalf of Tiger Asia to one count of wire fraud. Tiger Asia was sentenced to one year of probation and ordered to forfeit more than $16 million.

In the wake of the insider trading scandal, Goldman Sachs (GS) stopped doing business with Hwang for a period of time, a person familiar with the matter told CNN Business. However, Goldman Sachs later resumed a relationship with Hwang, serving as one of his firm's lenders.

Repeat of Long-Term Capital Management?

The blow-up of Archegos Capital brings back bad memories of Long-Term Capital Management. That massive hedge fund's collapse in 1998 threatened the financial system, forcing the federal government to intervene.

"This is likely not Long-Term Capital," Hogan said, citing reforms that mean banks hold less risk than before the 2008 crisis. "I don't think this is the tip of the iceberg."

Saluzzi, the Themis Trading executive, is not sure yet, pointing to how markets initially shrugged off the collapse of Bear Stearns hedge funds in the summer of 2007.

"We don't know how far the tentacles go," Saluzzi said. "Early in the Bear Stearns crisis, the market was fine ŌĆö until it wasn't."