The first observed interstellar object zipped through our solar system in October 2017 – and astronomers have been trying to understand it ever since.

Scientists scrambled to observe the object before it disappeared, moving along at 196,000 miles per hour, and their observations caused more questions than answers about the “oddball,” as scientists dubbed it.

Now, the latest research suggests it is a fragment of a Pluto-like planet from another solar system.

Steven Desch and Alan Jackson, two astrophysicists at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, have studied observations made of the unusual features of ‘Oumuamua. Their findings published Tuesday in two studies in the American Geophysical Union Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

After discovery, the object was dubbed ‘Oumuamua, Hawaiian for “a messenger that reaches out from the distant past.” At first, astronomers expected that it would be a comet.

That’s because comets can be tossed out of their host system through gravitational disturbances, and they’re also very visible. The second interstellar object discovered in our solar system was an interstellar comet, 2I/Borisov, observed in 2019.

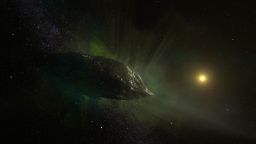

But the dry, rocky reddish, elongated cigar-shaped object, thick as a three-story building and half the length of a city block, had no cometary tail, and its tumbling motion couldn’t be explained. And debate has emerged over whether it’s an interstellar asteroid or comet.

And, of course, there was speculation that ‘Oumuamua was a type of alien probe.

“In many ways ‘Oumuamua resembled a comet, but it was peculiar enough in several ways that mystery surrounded its nature, and speculation ran rampant about what it was,” said Desch, who is also a professor at ASU, in a statement.

Clues from the rocket effect

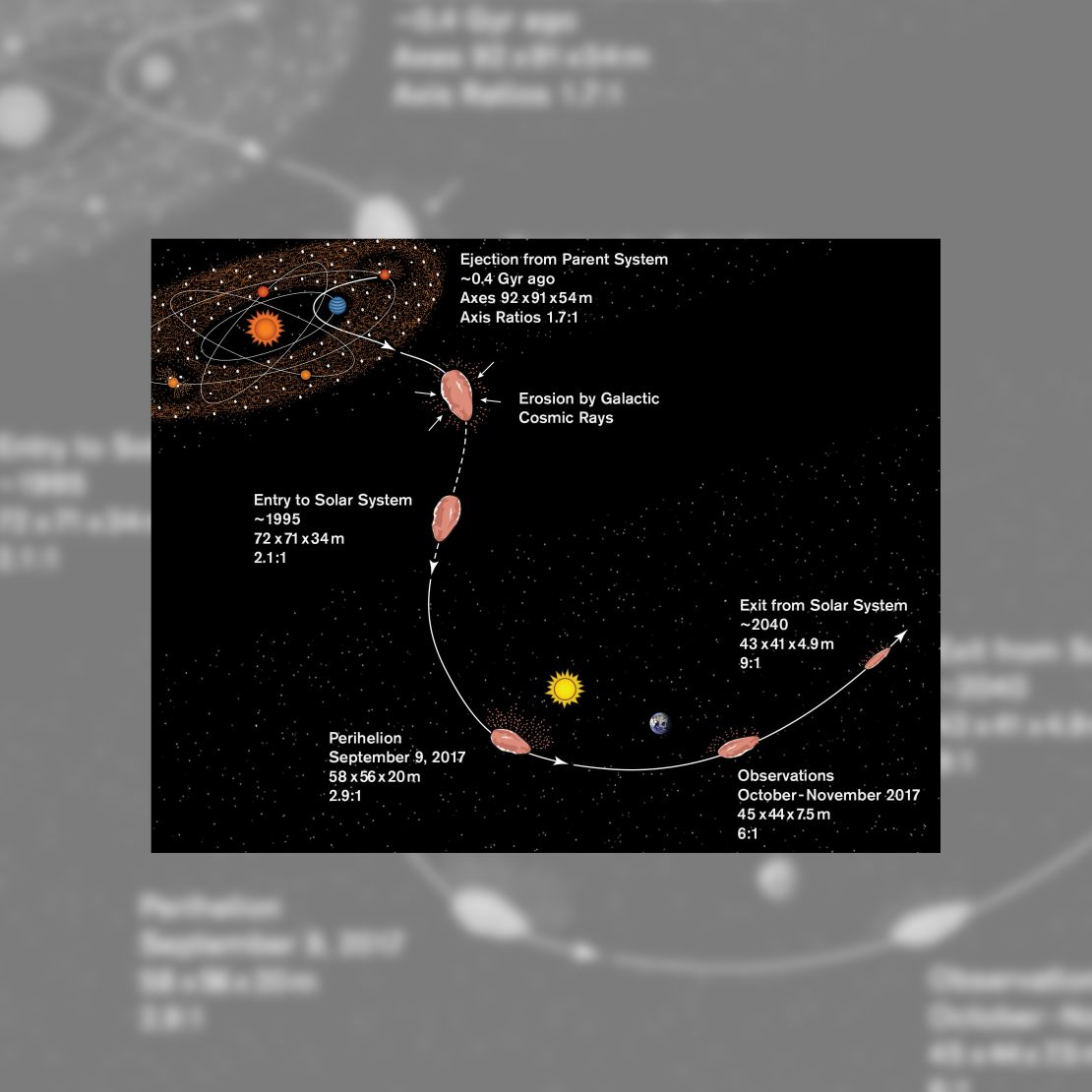

‘Oumuamua differed from comets in several ways, including the fact that it had a lower velocity as it entered our solar system. Had it been traveling across interstellar space for over a billion years as a comet, it would have had a higher velocity.

Its shape was flattened like a pancake, unlike comets which are like cosmic snowballs. The object also received quite a boost, known as the “rocket effect,” greater than what comets experience when their ices vaporize as they encounter the sun.

The researchers wondered if ‘Oumuamua was made of ices with different compositions, which allowed them to calculate how quickly the ices would turn to gas as the object zipped by the sun. This also allowed Desch and Jackson to determine the mass, shape and rocket effect and assess how reflective the ices were.

“We realized that a chunk of ice would be much more reflective than people were assuming, which meant it could be smaller. The same rocket effect would then give ‘Oumuamua a bigger push, bigger than comets usually experience,” Desch said.

Previous research has suggested that condensed water helped propel the object. In their study, Desch and Jackson found that solid nitrogen best matched the motion of ‘Oumuamua. The object was also shiny, with the same reflectivity of other known bodies made of nitrogen ice.

In our solar system, Pluto and Saturn’s moon Titan are mostly covered in nitrogen ice. If the object is largely composed of nitrogen ice, it’s possible that a solid chunk of it was dislodged from a Pluto-like planet after being impacted in another planetary system.

The same occurrence has happened in our own solar system, including Pluto and objects in the icy Kuiper Belt. This distant belt of objects on the edge of our solar system once had more mass than it does now.

When Neptune migrated to the outer solar system billions of years ago, it disrupted the orbits of these objects that were leftovers from the formation of the solar system. Thousands of objects similar to Pluto, covered in nitrogen ice, collided with each other.

If that could occur in our own solar system, it’s highly likely the same event could happen in another solar system, which means “‘Oumuamua may be the first sample of an exoplanet born around another star, brought to Earth,” the authors wrote in the study.

“It was likely knocked off the surface by an impact about half a billion years ago and thrown out of its parent system,” said Jackson, also a research scientist and an exploration fellow at ASU, in a statement.

“Being made of frozen nitrogen also explains the unusual shape of ‘Oumuamua. As the outer layers of nitrogen ice evaporated, the shape of the body would have become progressively more flattened, just like a bar of soap does as the outer layers get rubbed off through use.”

The researchers estimated that ‘Oumuamua’s encounter with our sun caused it to lose 95% of its mass.

Alien speculation

Theories that ‘Oumuamua is an alien object or piece of technology have circulated since the object appeared, and it’s the basis for the new book “Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth” by Avi Loeb, a professor of science at Harvard University.

There is no evidence to prove that ‘Oumuamua is alien technology, the researchers for this study said, although it’s natural that the first observed object from outside of our solar system would bring aliens to mind.

“But it’s important in science not to jump to conclusions,” Desch said. “It took two or three years to figure out a natural explanation — a chunk of nitrogen ice — that matches everything we know about ‘Oumuamua. That’s not that long in science, and far too soon to say we had exhausted all natural explanations.”

However, ‘Oumuamua has been a unique way for scientists to study an object from outside of our solar system. Understanding more about ‘Oumuamua, which disappeared from view in December 2017, can shed more light on the formation and composition of other planetary systems.

“Until now, we’ve had no way to know if other solar systems have Pluto-like planets, but now we have seen a chunk of one pass by Earth,” Desch said.

Future telescopes, like the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, will regularly survey the entirety of the sky visible from the Southern Hemisphere, increasing our ability to spot more interstellar objects that enter our solar system. The observatory will be operational beginning in 2022.

“It’s hoped that in a decade or so we can acquire statistics on what sorts of objects pass through the solar system, and if nitrogen ice chunks are rare or as common as we’ve calculated,” Jackson said. “Either way, we should be able to learn a lot about other solar systems, and whether they underwent the same sorts of collisional histories that ours did.”